Myanmar's Persecuted Rohingya Muslims Remain Stateless And Vulnerable After Risking Lives At Sea

To flee their home country, migrants in Southeast Asia have paid steep prices for space aboard unseaworthy ships with dwindling food supplies and horrific sanitary conditions. After weeks-long voyages on rickety, overcrowded boats, they were brought ashore to Malaysia and Indonesia where they were placed in government camps never intended for long-term living. The migrants receive humanitarian aid but are generally barred from leaving the camps, making it difficult to seek employment or education opportunities.

Southeast Asia's migrant crisis has seen thousands of Rohingya Muslims, a persecuted ethnic group from Myanmar, traverse the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea in recent months toward treacherous and uncertain futures. It's a risk the Rohingya are willing to take to avoid their status as stateless people in conflict-torn Myanmar, the country formerly known as Burma, where experts said deep religious and racial tensions have become unbearable for the minority population. But their plight is far from over. Indonesia and Malaysia are eager to close the camps within a year and send the migrants back out to sea. If the Rohingya are not granted asylum, they will likely become stateless victims yet again, vulnerable to exploitation, trafficking and institutionalized discrimination, experts said.

“They know the risks of getting on these boats,” said Bill Davis, a Myanmar researcher for Physicians for Human Rights, a nonprofit human rights group based in New York City. “They know they’re not going at all to the promised land. But now, that’s a better option than staying in Burma.”

'The Conditions Are Absolutely Dismal'

The Rohingya migrants have become globally known as the "boat people.” They are subject to violence, abduction, extortion, disease, dehydration and hunger. The south-bound vessels are captained by smugglers and crammed with hundreds of passengers, who pay up to a couple thousand dollars for the trip. Some captains have forced migrants into trafficking camps, while others have abandoned the ships, leaving the migrants stranded at sea. The dead bodies of dozens of suspected Rohingya migrants have washed up along Myanmar's jagged coast in recent weeks.

Women passengers go through menstrual cycles on the ships without proper latrines or feminine hygiene products, and those who fall ill are forced to sit in their own vomit and waste. Some migrants have spent months on boats because countries were not willing to take them in, experts said.

"Nobody would get in a boat under these conditions, unless they absolutely had to," said Melanie Nezer, vice president for policy and advocacy of HIAS, a Jewish organization that assists refugees. "What they're getting on the other side -- to think that's actually better -- you can understand how bleak the situation is for these people."

More than 4,000 migrants who were stranded at sea for weeks -- and in some cases, months -- have arrived at camps in Malaysia and Indonesia, which agreed last month to provide temporary shelter after weeks of saying the migrants weren’t welcome to come ashore. Thailand offered to provide humanitarian assistance but denied shelter, saying the country was already overloaded with tens of thousands of refugees from Myanmar.

Joe Lowry, the Asia Pacific spokesman for the International Organization for Migration, recently recalled the rescued migrants he saw while working at a camp in Indonesia's Aceh province. The severity of their malnutrition was shocking, he said. "Extremely, extremely thin. Some look quite skeletal," Lowry said in a telephone interview from Aceh. "The conditions are absolutely dismal."

'This is Not Over'

The rescued migrants who are brought ashore are provided food, shelter, clean water, clothes and medical care at the camps. They are also offered English lessons and psychotherapy. The refugees who wish to return home can do so without retribution and receive assistance filling out the necessary documents. Those who seek international protection can apply for asylum, experts said.

Rohingya Muslims are more culturally accepted in Malaysia, which has a Muslim-majority population, and in Indonesia, which has more Muslim citizens than any other country in the world. But the two host countries only agreed to shelter the migrants on condition they would return home or resettle in other countries within a year. Rohingya refugees lack legal rights in Indonesia and Malaysia, which make them vulnerable to exploitation and human trafficking. There are also more migrants believed to be adrift in the waters, waiting to be rescued, experts said.

“There are still so many people left at sea. This is not over,” Lowry said. "They have to be found and brought ashore."

About 88,000 people have tried to migrate by boat in Southeast Asia since 2014, and nearly 1,000 are believed to have perished due to the harsh conditions of the voyage, according to the United Nations. Many people from Bangladesh have also attempted the perilous journey south. Some are Bangladeshi citizens who fled the country’s unemployment and poverty. But others are suspected Rohingya refugees who fled from Myanmar, experts said.

'The Least Worst Place To Live -- Bangladesh Or Burma'

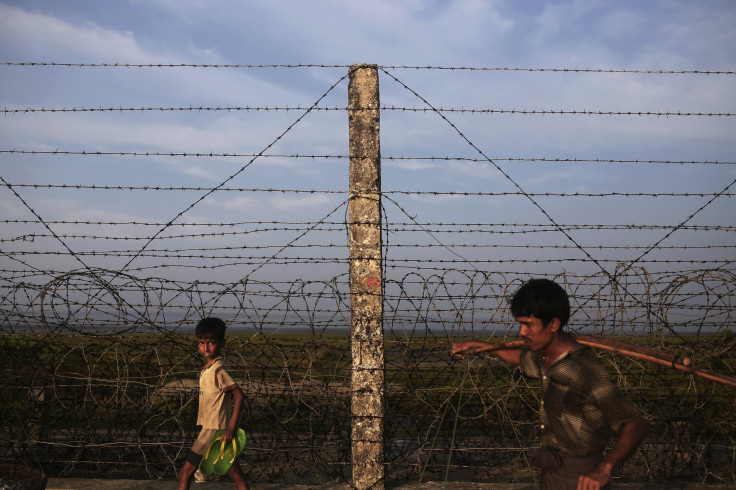

There are about 1 million Rohingya in Myanmar, who primarily reside in northern Rakhine state near the country’s border with Bangladesh. The minority group practices Sunni Islam and speaks Rohingya, an Indo-European language related to Bengali.

The ethnic group’s origin is disputed by the rival Buddhist majority population in Rakhine, who argue Rohingya Muslims are not indigenous to the state and thus should be denied citizenship. Some say the Rohingya migrated from Bengal, a region which is now Bangladesh and eastern India. An estimated 810,000 people in Rakhine state are currently without citizenship.

The Rohingya have faced persecution, discrimination and violence for decades, but the Burmese government has long denied it. Myanmar announced last year that the Rohingya can become official citizens in the Buddhist-majority nation only if they agree to be registered under another ethnicity and if they can verify their family has lived in the country for at least 60 years. The Burmese government, which recently transitioned from military rule to democracy, also revoked Rohingya voting rights, barring the ethnic group from participating in the November national elections. Myanmar enacted a new law in May that rights groups say targets Muslim women because it allows authorities to order women to wait three years between child births.

Government restrictions coupled with rising tensions between the Rohingya and Buddhists have caused intercommunal violence in recent years that has killed and uprooted thousands in Myanmar. About 140,000 persecuted Rohingya are internally displaced and live in overcrowded camps, where they still suffer abuse and unsanitary conditions. Some 100,000 others have fled the country, according to the United Nations refugee agency.

“One [Rohingya] woman told me she hadn’t eaten in three days because her family had to flee their village from violence,” said Davis, who was recently in the Burmese city of Yangon. “They ended up in a camp with just the clothes they had on. They had to borrow a cooking pot from their neighbors every day to cook their meals.”

There are also tens of thousands of undocumented Rohingya in northern Rakhine living in villages along the border with Bangladesh, barricaded by hostile authorities who restrict their movement and demand bribes at checkpoints, experts said. “They are paying these bribes and then they can’t buy food,” Davis said. “It’s become so impossible to make a living there.”

Bangladesh is hosting more than 200,000 Rohingya refugees from Myanmar. But life across the Bangladeshi border is not much better for the persecuted ethnic group. In Bangladesh, Rohingya refugees are viewed as illegal migrants and are barred from employment. Bangladeshi authorities have also imposed punitive restrictions on international organizations providing lifesaving aid to the refugees.

“It’s sort of like this back-and-forth of where’s the least worst place to live – Bangladesh or Burma,” Davis said during a Skype interview Tuesday from Thailand.

'They Want To Go Back'

Most internally displaced persons will remain displaced for a decade or more, and the Burmese government is likely to refuse Rohingya migrants access back into Myanmar. The chance of resettlement in third countries is also slim because few nations are willing to permanently house thousands of battered refugees, experts said.

But where would they like to go? Where would they like to live? Davis posed these questions to several Rohingya refugees he interviewed, and their answers were often the same. "They say I really want to go to my home and live in my home. I've heard this dozens of times," he said. "They want to go back to Rakhine state and live peacefully. I think they believe it's possible."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.