NAACP On Police Brutality: At Convention, Group Vows Relevance Amid Year Of 'Black Lives Matter' Protests

PHILADELPHIA – “It’s been a rough year.” Those were among the first words spoken Sunday night by presiding officer Leon Russell to attendees as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s national meeting was called to order, underscoring the series of travails the nation’s oldest civil rights organization had experienced during the past 12 months.

Since its last national gathering nearly one year ago in Las Vegas, the extinguished lives of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Tanisha Anderson, John Crawford III, Tony Robinson, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray and an untold number of other young African-Americans at the hands of police sent shock waves of protests through local communities and around the United States. However, the NAACP’s dignified calls for peaceful justice stood in stark contrast to massive youth-led demonstrations that took over city streets and sparked some violent clashes with police departments accused of unjustly ending black lives.

Those instances were followed by a surprising scandal in early June regarding the organization’s integrity after a white NAACP branch president in Washington state was revealed to have been masquerading as a black woman for years. That fizzled quickly, though, eclipsed by national tragedy when an armed white man entered a historically black church in Charleston, South Carolina and gunned down nine African-American worshipers attending Bible study, in a failed attempt to spark a race war.

It was in the wake of that terror attack on the black church -- a critical foundation for many civil rights organizations – that the NAACP seemingly rediscovered its voice, renewing a campaign launched 15 years ago to see a symbol of segregation and white supremacy stripped from places of prominence in the Deep South. Now, after claiming victory just days before its 106th convention began, leaders said the way forward required increased intensity in their collective fight against injustice.

Playing an integral role in the removal of the Confederate flag from the South Carolina Statehouse grounds has apparently reinvigorated the NAACP, which has prioritized the restoration of voting rights protections gutted by the Supreme Court in 2013 as its next order of business, its president Cornell William Brooks said.

But, perhaps most importantly, the organization wants a seat at the table -- locally and nationally -- on criminal justice and policing reforms, and plans to hammer home that point next month by continuing its tradition of nonviolent demonstrations with an 860-mile civil rights march from Selma, Alabama to Washington, D.C.

"I know that we are strong!” Brooks, who joined the organization exactly one year ago, said in a keynote address Monday evening. “I know that we are courageous! I know that we are powerful! I know that we will not stop! I know that we are here to stay!"

#NAACP106 defends liberal cons like #RachelDolezal but attacks conservatives who are actually black. #bcot #tcot #p2 pic.twitter.com/6Iv0cGBuKg

— Radiance Foundation (@lifehaspurpose) July 14, 2015Waltrina Middleton has high hopes for a national gathering of Black Lives Matter activists scheduled for next week in Cleveland, Ohio. The 36-year-old ordained minister and organizer of the “Movement for Black Lives Convening” wants to build on the last year of successes for a social campaign against police misconduct and excessive uses of lethal force in communities of color around the country.

“I think the outcry that you saw was one from those who are marginalized,” said Middleton, who commented as the NAACP prepared to wrap up its annual conclave Wednesday. “What you saw was an emergence of young new voices that did not come from the tradition.”

The growth of the Black Lives Matter movement, a social media campaign created to organize mass demonstrations where unarmed African-Americans had been killed at the hands of police, was hardly a denouncement of the more than century-old civil rights group, Middleton said. “One can’t deny the role that NAACP has played in [civil rights] progress,” she added. “For me, [the new movement] is a celebration of new ways to cry out for justice” that “did not discriminate with respect to gender, age or organization.”

There was a widespread acknowledgement at the Pennsylvania Convention Center among the NAACP leadership leaders that the Black Lives Matter campaign and its activists had changed the conversation around police brutality. Still, convention speakers repeatedly defended the organization’s standing and influence during mass meetings meant to reinvigorate the membership after a year of endless headlines about police brutality.

“To anybody who thinks we got weaker, we need to send them a newsflash,” said Rodney Muhammad, president of the Philadelphia branch of the NAACP. “We’ve gotten stronger.”

Founded in 1906 by an interracial group of citizens concerned about the unequal treatment and persecution of blacks in the U.S., the NAACP has been revered for providing strategic and political legwork that brought about an end to Jim Crow and other landmark achievements of the civil rights era. The Civil Right Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and a handful of Supreme Court challenges to the racial segregation of schools are among those achievements. Today, the NAACP says it prioritizes the protection of voting rights, reform of the criminal justice system, equality in public education and an expansion of access to healthcare in communities of color.

Specifically on police brutality, the organization said it would pressure state and federal lawmakers to address aggressive policing with training and diverse recruitment in communities of color. It wants body cameras to ensure accountability in policing and an elimination of officers’ biases that impact the way they perceive and treat people in communities of color.

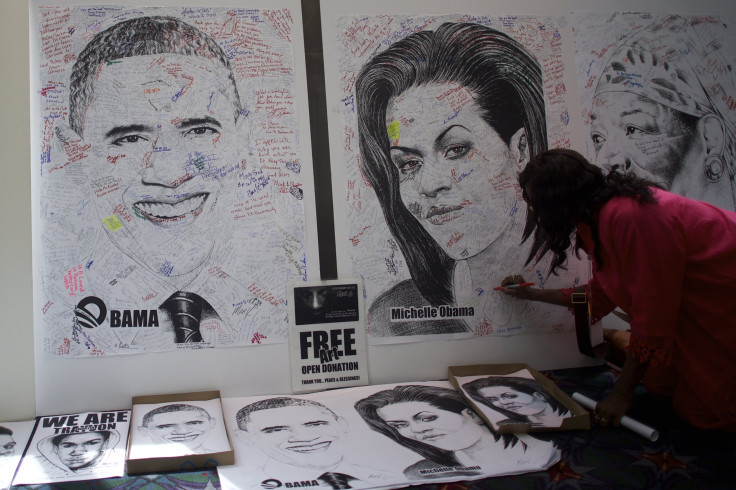

President Barack Obama Tuesday afternoon spoke of similar intentions while addressing thousands of convention-goers when he laid out a well-received criminal justice reform agenda, during which the nation’s commander-in-chief saluted the NAACP as an “organization that reshaped the nation.”

For Linda Haywood, president of the Flagler County branch of the NAACP in Palm Coast, Florida, a year of continuous youth-led protests was a testament to how faithful the NAACP had been to the civil rights era.

“We had so many incidences, it’s hard for the NAACP to be in all places at one time,” Haywood, 58, said of criticisms that the organization isn’t hip enough to carry the modern, social media savvy conversation on police brutality and injustice.

“The last year has worked the NAACP back to relevance,” Haywood said. “Our new president (Brooks) is going to bring us back to the forefront, where we deserve to be, as we were in the ‘50s and ‘60s.”

Ella K. Coffee, 43, of Tampa, Florida, said she hoped the NAACP would not waste an opportunity to harness the energy of the Black Lives Matter movement -- a Twitter hashtag campaign started after the 2013 acquittal of self-appointed neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teen in Florida, that evolved into mass demonstrations emulated around the world.

“The young people now have an opportunity to build on what was already there,” Coffee said. “Everybody has a role to play."

Dylann Roof, the 21-year-old Columbia, South Carolina man charged with murder in the massacre of nine people at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal, could not be lumped in with the year’s losses of young African-American lives by police, said NAACP chairman Roslyn Brock.

“This time was different,” Brock told members in a Sunday evening keynote address. “The sanctity of the black church was violated. We were done with pleading. We demanded real action, starting with the immediate removal of the Confederate battle flag.”

Following the June 18 arrest of Roof, officials unearthed photographs of the alleged shooter clutching a handgun and the same Confederate battle flag that was flying prominently over the South Caroling Statehouse complex. In 1999, the NAACP made South Carolina the epicenter of a debate on the flag symbolism’s and instituted a boycott of the state. After the flag was taken down July 10, the NAACP on Saturday called off its 15-year boycott.

“Our nation has a history of turning great adversity into beacons of hope and light,” Brock said, adding that “tearing down the symbols of bigotry and ending the language of hatred and exclusion is essential to changing hearts and minds and healing our nation of racism.”

Haywood, the Flagler County NAACP branch president, credited the organization for its leadership on the flag. “That boycott was the beginning of the end [for the flag,]” she said. “Anyone with a conscience honored that boycott because it was the NAACP that got behind it.”

Brock also wanted it known to convention attendees that the NAACP had been grooming a new generation of leadership. Brendien Mitchell, a 20-year-old junior at the historically black Howard University, was given a platform Tuesday to declare that millennials have a significant role to play in furthering the NAACP’s advocacy on police-community relations.

“The dynamic and common place of police brutality has caused us to lose our breath, raise our hands and say that black lives matter,” Mitchell said before approximately 4,000 people gathered in a convention hall for Obama remarks.

The Black Lives Matter’s prominence “left many questioning if the NAACP is still getting the job done,” he said. “We must fight on to see what the end is going be!”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.