NASA Study Reveals Effect Of Largest Animal Migration On Climate

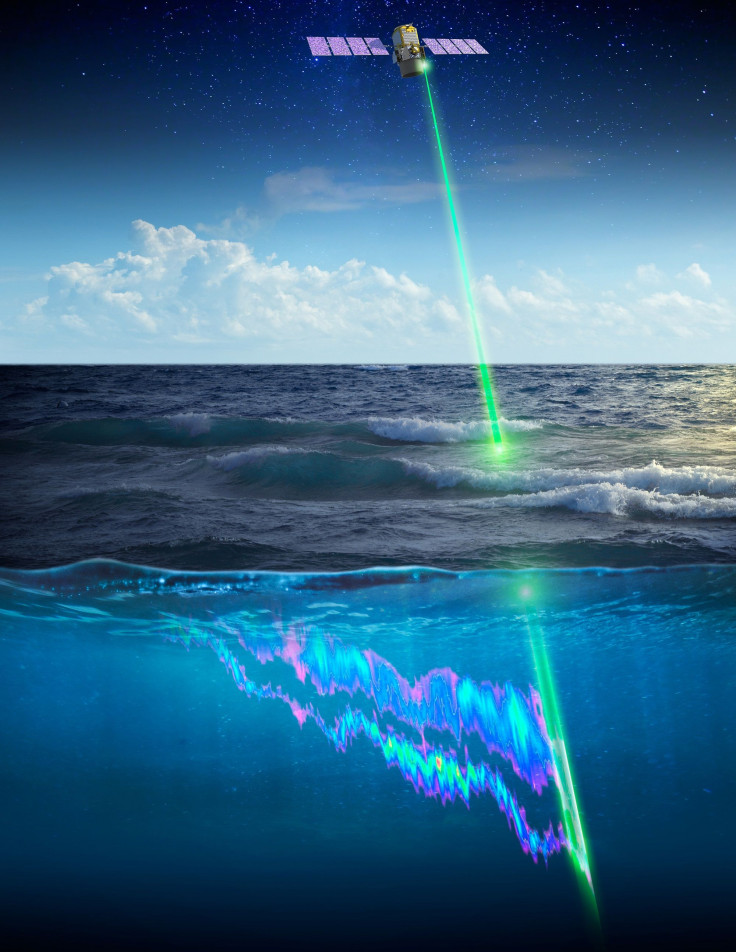

NASA released a new study detailing the largest known migration of ocean animals and its direct effect on Earth’s climate. The agency was able to monitor the migration using a space-based laser from a satellite.

The entire study lasted for 10 years and was carried out using the Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observations (CALIPSO) through a collaborative effort between researchers from NASA and the French space agency Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales.

For the study, the researchers used CALIPSO’s laser capabilities to keep track of the movement and behavior of small ocean animals such as squids and krill from space. They focused on a natural phenomenon known as the Diel Vertical Migration (DVM), which occurs daily.

According to the researchers, this kind of migration happens when small creatures leave the depths of the ocean to feed on phytoplankton near the surface. Due to the large number of animals that participate in DVM, it has been considered as the largest migration of living creatures on Earth.

Through CALIPSO, researchers were able to monitor this behavior and even keep track of its overall effect on Earth’s climate.

“This is the latest study to demonstrate something that came as a surprise to many: that lidars have the sensitivity to provide scientifically useful ocean measurements from space,” Chris Hostetler of NASA's Langley Research Center and co-author of the study said in a statement. "I think we are just scratching the surface of exciting new ocean science that can be accomplished with lidar.”

According to the researchers, DVM affects the climate because during the day, the phytoplankton near the ocean’s surface photosynthesize, which enables them to absorb high levels of carbon dioxide. In turn, the phytoplankton’s behavior increases the amount of greenhouse gas from the atmosphere absorbed by the ocean.

As the small animals feed on the surface, they also consume the phytoplankton carbon. This is then defecated into the depths after the return of the ocean creatures. According to the researchers, this prevents the carbon from being released back into the atmosphere.

Due to the large number of animals that participate in DVM, the amount of carbon that is prevented from returning to the atmosphere contribute in slowing down global warming.

“The new satellite data give us an opportunity to combine satellite observations with the models and do a better job quantifying the impact of this enormous animal migration on Earth’s carbon cycle,” Mike Behrenfeld, the lead author of the study, explained.

The study carried out by the researchers was published in the journal Nature.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.