NASA Telescopes Discover Clear Skies And Water Vapor On Neptune-Sized Gaseous Exoplanet

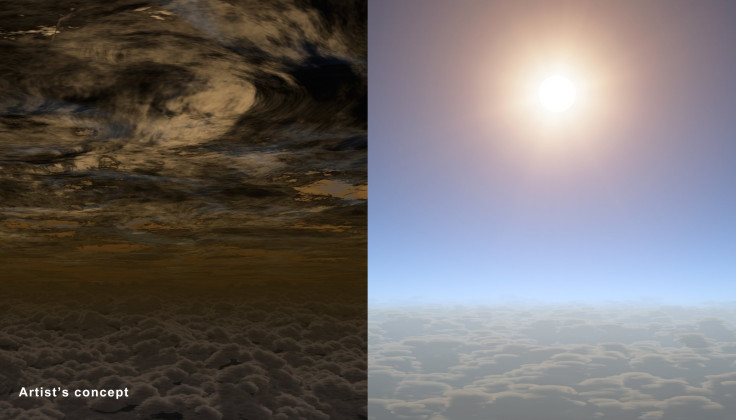

Data from three of NASA’s space telescopes have helped astronomers discover clear skies and water vapor on a gaseous planet outside our solar system. The exoplanet, which is about the size of Neptune, is the smallest exoplanet from which molecules of any kind have been detected.

According to NASA, astronomers made the discovery by analyzing data from the agency’s Hubble, Spitzer and Kepler space telescopes. The latest findings are expected to help scientists better examine the atmospheric composition of smaller, rocky planets similar to Earth, astronomers said in a study, published in the journal Nature.

“When astronomers go observing at night with telescopes, they say 'clear skies' to mean good luck,” Jonathan Fraine of the University of Maryland, and the study’s lead author, said in a statement. “In this case, we found clear skies on a distant planet. That's lucky for us because it means clouds didn't block our view of water molecules.”

The Neptune-sized exoplanet, dubbed HAT-P-11b, orbits a star called HAT-P-1, taking about five days to complete one lap. The planet, which is located 120 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus, is a warm world and is believed to have a rocky core and gaseous atmosphere.

“We think that exo-Neptunes may have diverse compositions, which reflect their formation histories,” Heather Knutson of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, and the study’s co-author, said in the statement. “Now with data like these, we can begin to piece together a narrative for the origin of these distant worlds.”

According to scientists, the results from all the three telescopes showed that HAT-P-11b is covered in water vapor, hydrogen gas and other molecules that are yet to be identified.

“We are working our way down the line, from hot Jupiters to exo-Neptunes,” Drake Deming, a co-author of the study, said. “We want to expand our knowledge to a diverse range of exoplanets.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.