Neanderthals’ History Of Incest: DNA Shows Evidence Of Early Human Interbreeding

An international team of researchers used a high-quality genome sequence of a Neanderthal woman to reveal a long history of incestuous relationships among at least four different types of early humans who lived in Europe and Asia thousands of years ago.

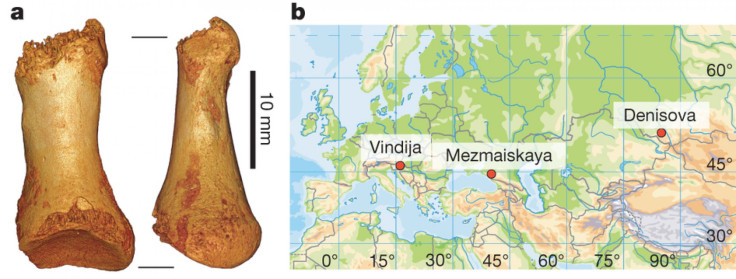

The researchers led by Kay Prüfer and Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, extracted DNA from the Neanderthal woman’s toe bone, which dates back 50,000 years. The genome provided detailed insights into the relationships and population history of Neanderthals and other extinct early human groups, and produced results revealing that interbreeding led to a common gene flow among such groups.

“The paper really shows that the history of humans and hominins during this period was very complicated,” Montgomery Slatkin, a professor of integrative biology at the University of California at Berkeley, who was part of the research team, said in a statement. “There was lot of interbreeding that we know about and probably other interbreeding we haven’t yet discovered.”

The researchers compared a high-quality sequence of the Neanderthal genome to the genomes of modern humans, and a recently recognized group of early humans called Denisovans, to find that Neanderthals and Denisovans were closely related. And though the Denisovans and Neanderthals eventually died out, they left behind bits of their genetic heritage because they occasionally interbred with the ancestors of modern humans.

According to the study, published in the Dec. 18 issue of the journal Nature, the fraction of Neanderthal-derived DNA in the genomes of people outside Africa varies approximately 1.5 percent to 2.1 percent. The new data also show that approximately 0.2 percent of the genomes of mainland Asians and Native Americans are of Denisovan origin.

The study revealed that Neanderthals contributed at least 0.5 percent of their DNA to the Denisovans. However, the Denisovan genome differs from the Neanderthal genome in that it contains about 2.7 to 5.8 percent of the genome of an unknown group of early humans, which is presumably the group of modern-human ancestors known as Homo erectus, who lived in Europe and Asia a million or more years ago.

Neanderthal Woman Was Inbred

While analyzing the genome of the Neanderthal woman, the researchers found that her parents were closely related to each other. Further analyses also suggested that the population sizes of Neanderthals and Denisovans were small, and that inbreeding may have been more common in Neanderthal groups than in modern populations.

“We performed simulations of several inbreeding scenarios and discovered that the parents of this Neandertal individual were either half siblings who had a mother in common, double first cousins, an uncle and a niece, an aunt and a nephew, a grandfather and a granddaughter, or a grandmother and a grandson,” Slatkin, who led some of the analyses of the genome, said in a statement.

The Neanderthal toe bone in question was found in the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Southern Siberia in 2010. The cave also contains modern human artifacts, suggesting that at least three groups of early humans occupied the cave at different times.

The study also helped identify a list of at least 87 specific genes in modern humans that are significantly different from related genes in Neanderthals and Denisovans. According to the researchers, this uniqueness may hold clues to the behavioral differences distinguishing modern humans from early human populations.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.