North Korea Then And Now: Inside The Hermit Kingdom, 18 Years After My Parents And Two Years Into The Reign of Kim Jong-Un [PHOTOS]

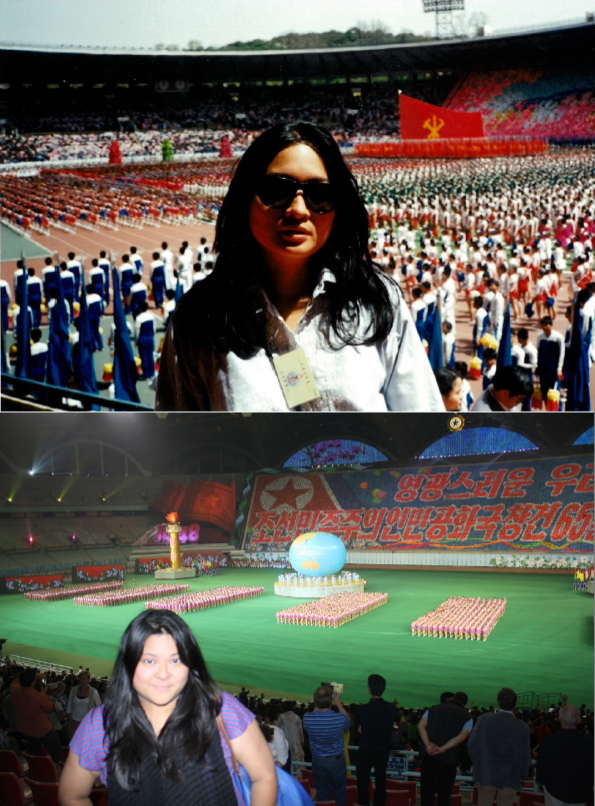

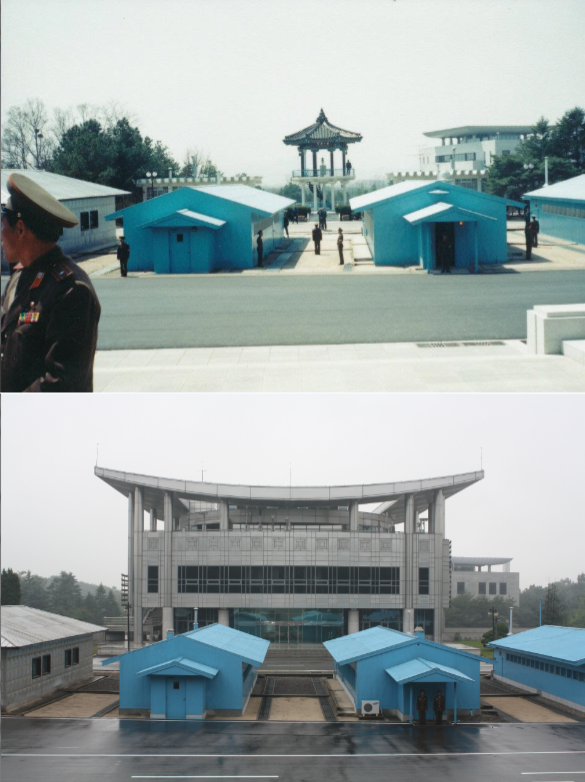

During the spring of 1995, about 20 China-based foreign journalists packed their bags and jetted off for a rare, weeklong trip to Pyongyang, North Korea, a nation even more isolated at the time than it is now. Among them was Jaime FlorCruz, then the Beijing correspondent for Time magazine, and his wife, Ana, who tagged along for the trip: my mom and dad. The group did what anyone else would do: They hit the tourist spots and posed for photos.

My father, who has now been to North Korea three times, began urging me to visit the famously dubbed “hermit kingdom” while I was attending high school just a stone's throw away in Beijing. Aside from the grand monuments and the country's proud, and ever-present, Juche, or "self-sufficiency" ideals, my dad saw a unique and complicated country that was in some ways a last frontier -- a place that he said was like stepping back in time. He was reminded of his experience in post-Cultural Revolution China in the 1970s, with how tightly restricted information was. He said he sensed a hunger for information among the people, an inkling of bottled-up creativity and stifled entrepreneurship. Aesthetically, even the newer buildings and landmarks were odes to dated Stalinist design concepts, something that had been long-abandoned by the late 20th century. As its neighbors South Korea and China began to rapidly move forward and grow, the North felt frozen in time. None of which really interested me at the time.

At 15 years old, the thought of spending my spring break in North Korea was about as appealing as -- well, spending my spring break in North Korea. Seven years later, my attitude toward traveling to Pyongyang has changed quite a bit. For a combination of reasons, including North Korea's bellicose nuclear threats and the nation's new headline-stealing leader, the 31-year-old Kim Jong-un, I found myself growing curious to see what my parents were talking about. Through news headlines I saw that North Korea was going through a period of change, with many around the world trying to figure out which direction Kim would take the country.

Mild curiosity quickly snowballed into an obsession once China, the country where I was predominately raised, began to play a bigger role in the controversy over North Korea's nuclear weapons program. The two countries have had a longstanding, almost familial alliance for decades. That relationship is still there, but it has become strained as tensions flare over North Korea's threats to use nuclear force against the West, which jeopardizes China's mutual economic interests with the U.S.

My father expected that my experience in the perennially defiant, secretive nation would largely mirror his and my mothers' experience, and in many ways it did. But whereas North Korea in 1995 was determined to stay under the world's radar, its leaders now seem to savor global curiosity, which they pique by being unforthcoming and mysteriously erratic.

All of this made North Korea more attractive and intriguing as a destination, so I booked my trip through Koryo Tours, the North Korea-specialized tourism group that also brought my parents delegation over, and in early September found myself on the Beijing Capital Airport tarmac, waiting to take off for Pyongyang. Before I left, my parents dug up old family photo albums and showed me pictures from their trip, which served as a bit of a primer on what I could expect to see.

Once I got to North Korea, my tour group made a lot of the same stops that my parents did, producing similar Kodak moments, only one generation later.

Some highlights from the trip my parents took included not-so-standard tourist attractions, including happily indulging in a few holes on a golf course, a high-class sport that seems out of place in North Korea, and even a chance encounter outside a hotel with boxing champion Muhammad Ali.

Former heavyweight champion Ali was in North Korea as part of a group of professional foreign wrestlers for an event called the International Sports and Cultural Festival for Peace in Pyongyang. The event was seen as a way to lure foreigners and tourists to the capital and give North Korea some needed positive attention. It took place roughly a year after the death of President Kim Il Sung, as his son, General Kim Jung Il, adjusted to his new role as the nation’s leader.

During my visit, I never got the chance to be on the putting green, or shake the hand of a boxing legend, but the parallels between then and now were still very apparent. I found myself being fitted for a pair of bowling shoes and playing a full 10-frame game (I had no idea that the Koreans played such a Western sport) and sharing the city with a much different but still iconic American athlete: NBA superstar Dennis Rodman, whose weird and somewhat controversial visit overlapped my stay in Pyongyang for one day. Rodman, like Ali, is famous for his wild antics -- in his case, such as sporting a wedding dress as a publicity stunt to promote his autobiography in the 1990s -- and equally wild fashion sense. Rodman was there on his second highly publicized “basketball diplomacy” tour; his first trip to North Korea in March occurred a little more than a year after the death of Kim Jong Il in December of 2011. Kim Jong Il’s successor and youngest son, the basketball-fanatic Kim Jong Un, is in a situation similar to his father's almost two decades ago, stepping into a new role as the all-powerful leader of an extremely poor and isolated country.

Also during my tour I visited computer study labs -- quiet rooms filled with North Koreans sitting in front of neat rows of glowing monitors connected only to an Intranet server with access to what appeared be digital versions of various Korean publications, located at the Grand People’s Study House. The silence was sometimes unnerving. The Study House, which is the capital’s library and lecture hall, didn’t have computer labs back when my dad first visited, he said. Instead, he and my mom were escorted into similarly organized (and silent) study rooms filled with people at lines of desks reading books. Our tour guide for the building, Kim, coincidentally was the same man who showed Google CEO Eric Schmidt and the rest of the company's delegation around during his visit in January. He sat us down at one of the computers and told us to yell out subjects for him to search. “USA,” someone called out. The search returned several hundred, if not thousands, of results, most of which were scientific publications.

As we weaved through the sprawling facility, a few hallways over was the “music appreciation room,” a large study area lined with desks, each equipped with old-school boom boxes. Our guide, a funny character who immediately shouted “rum!” when I told him I was a native of the Philippines, popped in a Beatles compilation CD in one of the boom boxes and insisted on a singalong to “Yellow Submarine,” a song he insisted that everyone (even North Koreans, apparently), knew the words to. I picked up the CD jewel case to see what other tracks North Koreans were able to “appreciate” and found that among them was “Michelle,” the song off the Rubber Soul album that my Beatles-fanatic father named me after.

I tell people who ask about my trip that regardless of the current state of the North Korea's politics or economy, it is fascinating place to visit precisely because it's so different from the world we inhabit in the West, and even in the East. Going there allows foreigners to see the country and the world from a different perspective. While most people only understand North Korea through the lens of the media or propaganda, a first-hand peek into the country, even a small one, helps decipher the enigmatic nation or at least humanize it.

The North Koreans in the capital and the guides on our tour were more candid than you'd expect, talking relatively freely about the quotidian and their aspirations. One guide said that his dream was to live an average and happy life with his wife and new daughter. He added that he had no desire to have access to the 'real' Internet, too much dangerous and perhaps untruthful information. Hopes such as these may feel limited to the rest of the world but not to many North Koreans. In addition, there were several moments of genuine, unfiltered curiosity about life outside of the country -- questions about how dating differs in the West and discussions about school and sports.

One of the strangest things for me about North Korea, in fact, was that it didn't really seem all that strange. But maybe that's because I had, in a way, seen it all before, through my parents' eyes.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.