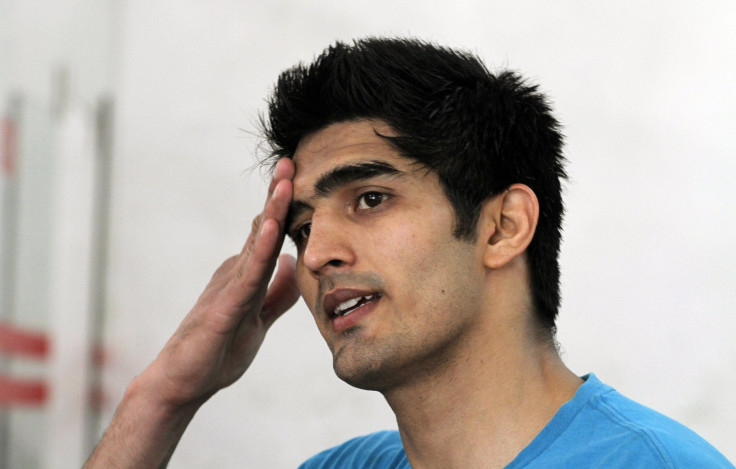

Olympic Boxer Vijender Singh Accused Of Heroin Abuse: The Drug Epidemic Sweeping Across India’s Punjab

Allegations by police that Olympic boxer Vijender Singh consumed heroin underscores the drug abuse epidemic sweeping across India’s Punjab province.

According to a report from the Press Trust of India, or PTI, Punjab Police claim that Singh used heroin a dozen times after acquiring it from smugglers, while his sparring partner, Ram Singh, consumed the drug five times between December 2012 and February 2013.

Vijender, who became the first Indian boxer to win an Olympic medal when he appeared at the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing, has denied any involvement with drugs.

The Indian sports ministry has asked the National Anti-Doping Agency, or NADA, to immediately conduct drug tests on Vijender in an effort to clear the air surrounding the famed boxer.

"Such reports in respect of a sporting icon are disturbing and may have a debilitating influence on other sportspersons in the country,” the ministry said in a statement.

It is unclear if Vijender will agree to take the test or what his current legal status is with respect to the drug allegations.

Regardless of Vijender Singh’s guilt, drug abuse is a major problem in his native Punjab.

Punjab is one of the wealthiest parts of India, but its high unemployment rate, slowing economy and proximity to Pakistan and Afghanistan makes its young men highly vulnerable to addiction to illegal narcotics, particularly opium, hashish and heroin.

In the past two decades, Punjab has become a principal smuggling route for drugs from Afghanistan ultimately destined for Europe, but much of the product has found an eager market in India.

Attempts by the Indian government to seal the border with Pakistan have only pushed up the price of drugs, including heroin, forcing addicts to gravitate toward cheaper over-the-counter pharmaceuticals that produce a similar high. These latter drugs are almost entirely manufactured within India itself.

According to a report in the Washington Post, the town of Maqboolpura, outside Amritsar, near the Pakistani border, has been so devastated by the deadly scourge of drug abuse it has earned the sobriquet “the place of widows.”

"The situation here is pathetic, pathetic," local school director Brij Bedi told BBC.

"We encounter drug addicts in the daytime. Sometimes, they become very violent also. They're drunk or have taken drugs. Sometimes they try to abuse also. ... The police know exactly who sells the drugs, but the tragedy is they are helpless. They are gutless people."

Drug seizures have increased by 200 percent over just the past two years in Punjab, which accounts for more than 50 percent of all heroin seized by Indian police annually.

“[Drugs are] a very big problem, and our youth is being engulfed in it,” sociologist Ravinder Singh Sandhu told the Post. “Punjabis are very aspirational people, and, when their aspirations are not fulfilled, then they are depressed.”

The local government estimated in 2009 that two-thirds of all rural households in Punjab had at least one drug addict.

Official corruption worsens the problem -- anecdotal evidence strongly indicates that Indian police and lawmakers are deeply complicit in both drug smuggling and distribution, netting millions of dollars in ill-gotten proceeds.

For example, in 2009, Saji Mohan, a senior police narcotics chief from Chandigarh, the capital of Punjab, was arrested in Mumbai and charged with selling heroin.

“It’s basically the police who are smuggling half the drugs in the state,” one unidentified man told the Post.

“If they confiscate 100 packets, police show 50 to the press and let the other 50 back into the market.”

A report in the New York Times noted that in the Punjab schoolboys often eat small black balls of opium paste, with tea, before classes.

Heroin also plays a role in Punjab elections -- the Indian Express reported that police have in the past uncovered a conspiracy by political party officials to provide drugs to constituents in order to guarantee votes (they have also plied their targets with cheap alcohol for the same purpose).

"It is a very disturbing sign,” a senior Punjab Police official told the paper.

“In previous elections, liquor and local drugs like poppy husk used to be distributed to lure voters. But, the seizure of such huge quantities of heroin this time is worrisome. And for every [kilogram] of heroin that has been seized, there would be a [kilogram] that has not been found.”

In tandem with this surge in drug abuse, an increasing number of Punjabi addicts are injecting heroin instead of smoking it, leading to a spike in HIV/AIDS infections.

"It's as if we're sitting on a time bomb that can explode at any time," Dr. J.P.S. Bhatia, who operates a rehabilitation clinic in the city of Amritsar, told BBC.

"[The rate of addiction] is definitely on the rise, and it is increasing so much that the scenario at the moment is that of an epidemic.”

Punjab also has a very macho culture, very prone to consumerism, violence and showing off.

“It’s a ready-made market for drugs,” former addict Navneet Singh told Agence France-Presse.

“What does the [typical] Punjabi do when he gets rich? He buys an SUV, a gun, and he gets high. Then as time passes and you get addicted, you will do anything to support the habit.”

Rates of drug-related crime in Punjab are almost 10 times the national average for India, AFP reported, citing police records.

Last April, India’s First Post newspaper described Punjab’s drug problem as “gargantuan.”

"Punjab is teetering on the edge of an extraordinary human crisis, with an inordinately large number of youngsters hooked on ... marijuana, opium and heroin, in addition to imbibing a range of prescriptive tablets,” Raj Pal Meena, the former head of the state's Anti-Narcotics Task Force, said.

With a population of about 28 million, only 51 drug rehabilitation centers exist in Punjab, currently treating about 5,000 addicts, according to the Hindustan Times.

"The number of addicts admitted in each center was 80 to 85 [until] 2007 and has now gone up to 190 in some centers,” Amanjeet Singh, president of the Punjab State Drug Counseling and Rehabilitation Centers Union, told the paper.

Drugs are also a serious problem in Punjabi prisons. About 62 percent of the province’s inmates are estimated to be drug abusers, and one-fifth are hard-core addicts. As with other institutions in Punjab, the jail system is woefully ill-equipped to cope with incarcerated drug addicts.

"It's a drug hurricane," Harjit Singh, secretary of Punjab’s Department of Social Security, gravely warned India Today. "We are in danger of losing our young generation."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.