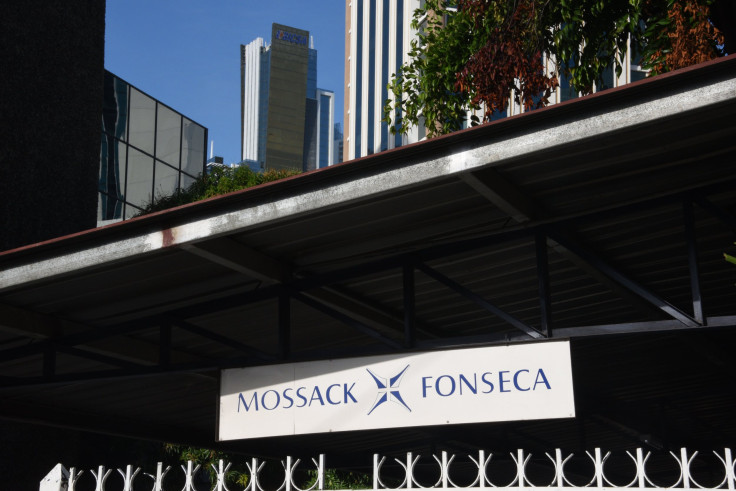

Panama Papers: At Least 38 US Citizens Named In Massive Leak Of Offshore Data From Mossack Fonseca

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists released on Monday a searchable database of connections found in the Panama Papers, the massive data dump of offshore companies linked to the world’s rich and powerful. And along with it were more details about the few U.S. citizens found in a massive list that includes heads of state or their relatives, political party chiefs, sports stars, actors and Nobel-winning novelists.

So far, the only high-profile U.S. names that have been made public in recent months have been music and film mogul David Geffen and the late filmmaker Stanley Kubrick. But new details released Monday by the ICIJ outed more U.S. citizens. Albeit not as famous as the co-founder of DreamWorks Pictures or the director of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” as many as 36 other U.S. citizens have been linked to accusations of fraud or other financial misconduct that should have raised red flags with Mossack Fonseca, the Panama-based global law firm from which the documents were taken by an anonymous leaker, the ICIJ says.

Mossack Fonseca denies any wrongdoing. The new names include the son of a civil rights-era murderer behind a failed Caribbean-based insurance company and a group accused of ripping off thousands of Indonesian investors.

Establishing an offshore company or trust isn’t illegal, but the Panama Papers underscores the shade in which both legal and illegal activity can take place pitting a country’s tax and secrecy laws against another country’s effort to root out tax evaders and hunt down crooks exploiting opaque corporate registration rules used by privacy-seeking law abiders.

“Fraudsters like offshore because of the lack of transparency,” Ellen Zimiles, a former federal prosecutor in New York who now leads Navigant Consulting’s investigations and compliance practice, told the ICIJ in its report on U.S. citizens named in the Panama Papers that was published Monday. When offshore structures are put together skillfully, “it takes a lot of time for investigators to get the ultimate beneficiary.”

Two of the new names to emerge from the Panama Papers are convicted fraudster Martin Frankel, the Connecticut Ponzi scheme operator who served 16 years for investment fraud, and Leonard Gotshalk, the former Atlanta Falcons football player turned Oregon businessman who served time for defrauding lenders. Gotshalk faces a May 19 hearing related to allegations he violated securities law, the ICIJ reported. Both men used Mossack Fonseca’s services and though no direct links have been made between their offshore activates and the laws they broke, it suggests the firm’s compliance team failed to identify potentially risky clients.

Another case involves six Americans, including a former Sears appliance salesman and a disbarred attorney and Las Vegas bus driver, accused of running Dressel Investment Ltd., a shell company set up by Mossack Fonseca that defrauded thousands of Indonesians out of nearly $100 million.

The firm also set up two shell companies for Robert Miracle, a Seattle-based businessman who pleaded guilty to crimes and went to prison for charges related to targeting Indonesians in a fraudulent oil and gas deal. In the summer of 2008, months after the investigation into Miracle’s activities became public knowledge, Mossack Fonseca set up the second shell company, Fivex Trading Ltd., listing two Malaysian fugitives linked to Miracle’s Ponzi scheme and Miracle’s daughter as shareholders.

Mississippi businessman Harvey Milam is another U.S. name that has popped up in connection to Mossack Fonseca. A client of the firm’s U.S. representative, Michael B. Edge, Milam and other defendants settled out of court in 2012 against investors who claim Milam defrauded them out of assets from a failed insurance company established in the Caribbean island of Nevis. Milam is the son of the late J.W. Milam, one of the men behind the 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till that helped kick off the U.S. civil rights movement.

The relatively small number of U.S. citizens so far named in the Panama Papers is not an indication that Americans are more honest, but rather that Americans have had plenty of options to choose from, both at home and abroad, in English-speaking tax havens.

Fear of scrutiny from U.S. law enforcement (which has been particularly concerned about drug-trade money laundering and terrorist-financing activities) also led Mossack Fonseca to be wary of U.S. clients. In 2008, Edge was named an “unofficial” representative of the firm out of concern over scrutiny by the FBI, an internal email from the firm in the Panama Papers reads.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.