Peabody Energy Corp (BTU) Bankruptcy Marks A Critical New Low For The Struggling US Coal Industry

Peabody Energy Corp.’s bankruptcy filing Wednesday marks a critical new low for the long-struggling U.S. coal industry.

The nation’s biggest coal company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection after a sharp drop in coal prices, the sluggish Chinese economy and cheap natural gas left the miner unable to service debt worth $10.1 billion. The coal market's downturn has already pushed its rivals Arch Coal Inc., Alpha Natural Resources Inc. and dozens of other coal producers to seek bankruptcy protection in recent years.

Peabody’s struggles reflect the broader forces rippling across America’s coal country that will likely change the industry in a permanent way. Surging natural gas production, growing concerns about climate change and stagnant electricity demand won’t eliminate the need for coal, but it could result in fewer players mining increasingly smaller volumes of coal, analysts said.

“There’s still a place for coal in the market. But the market is shrinking and has shrunk,” said Dale Hazelton, a senior coal research manager at Wood Mackenzie in Maryland.

Despite the headwinds, hundreds of U.S. coal mines are still profitable and operating. St. Louis-based Peabody said all of its U.S. operations were cash-flow positive in 2015, and its Australian business earned more money last year than in 2014 despite lower prices for coal.

Peabody said Wednesday it expected its mines in the U.S. and Australia to continue to operate as usual during the bankruptcy proceedings. The Chapter 11 filing “enables us to strengthen liquidity and reduce debt … and lay the foundation for long-term stability and success in the future,” Peabody CEO Glenn Kellow said in a statement.

Shares of Peabody (NYSE:BTU) were halted Wednesday after closing on Tuesday at $2.06 — a 97 percent drop from the firm’s share price a year ago.

The company’s heavy debt burden made it harder for the company to navigate the rocky market. Peabody, like its competitors, made expensive acquisitions in recent years as it sought to grab a share of what was then a booming Asian import market. Peabody bought Macarthur Coal in Australia for $5.1 billion in 2011, just as prices peaked for the metallurgical coal used in Asian steel mills, at around $330 a metric ton. As the region’s economies cooled, particularly in China, demand for steelmaking coal stalled and prices plunged nearly 75 percent, to about $83 a ton today.

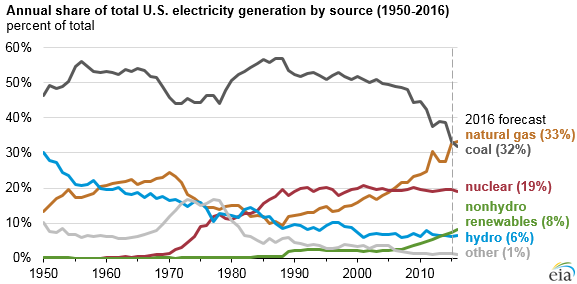

Peabody took a $700 million write-down on its Australian metallurgical coal assets last year. That compounded its financial woes in the U.S. market for thermal coal, the type burned in power plants. With low natural gas prices, tougher air pollution limits and an oversupply of coal, total U.S. coal production fell to about 900 million short tons last year, its lowest level in nearly three decades, the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated. In 2016, natural gas-fired power for the first time could overtake coal plants as the No. 1 source of electricity, the agency said.

All of these problems are expected to persist for at least the next 12 months, according to analysts at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

“A rebound in [Peabody]’s share price is contingent on increase demand for [metallurgical] coal in Asia and a decline in the supply of natural gas in North America, two potential catalysts that are unlikely in the short-to-intermediate term,” they wrote in a recent report.

Within a few years, however, the markets could reconfigure in the coal companies’ favor, Hazelton said. As the world steadily eats away at the oversupply of metallurgical and thermal coal, prices will begin to recover. Resurging demand from Asian steel mills and a slowdown in U.S. shale drilling — which is already starting to happen — will further increase the demand for coal.

“It’s a tough road, but there’s still money to be made,” Hazelton said.

He said an era of “mega-mergers” was unlikely to follow as the market improved, given the headaches these expensive acquisitions are causing miners today. For instance, Alpha Natural Resources bought Massey Energy in 2011 for $7.1 billion in cash and stock; four years later it filed for bankruptcy protection. Instead, smaller companies could become midsize companies as they gobble up assets, while most miners could remain or become private companies, instead of public firms beholden to shareholders, Hazelton said.

Even if some of the pain disappears from U.S. coal markets, however, the industry isn’t expected to fully return to its glory days. The last time U.S. coal production surpassed 1 billion short tons was in 2011. “We probably won’t see that again,” Hazelton said. “But likewise it also won’t be zero.”

Stronger climate change policies and tighter limits on greenhouse gas emissions could also hasten the long-term decline of coal. The Obama administration last year finalized the Clean Power Plan to force states to curb carbon from existing power plants and adopt cleaner energy sources, although the rule is mired in an ongoing legal battle. In December, nearly 200 nations in Paris adopted a global accord to tackle climate change. President Obama said he will formally sign the pledge at an April 22 ceremony in New York City.

Environmental groups are also working state-by-state to compel the closure of more than 500 U.S. coal-fired power plants. The Sierra Club said 232 plants have announced plans to retire since 2010, with dozens more retirements expected to occur this year and next. Green groups and regional organizations said they are also fighting to ensure that the bankrupt coal companies clean up their mine sites and protect local air and water supplies.

Peabody, for instance, holds more than $2 billion in financial liabilities for the cleanup of its U.S. mines, according to the Powder River Basin Resource Council, a community group in Wyoming.

Mary Anne Hitt, director of Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, said the Peabody bankruptcy filing marks “a turning point” for the U.S. coal sector.

“The days when they were the king of the hill are clearly behind us,” she said. “It’s now on all of us to do everything we can to make sure that the communities and the workers and the land are not the ones that pay the price.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.