Why Banks Want To Save The National Flood Insurance Program

The last six months of the year have seen a surge in lobbying activity on the National Flood Insurance Program, a nearly $25-billion-indebted federal safety net for buildings whose flood risks are too costly for private insurers that was up for reauthorization in early September. On Sept. 8, many of the lobbyists won a temporary victory when President Donald Trump signed congressional legislation kicking the NFIP expiration date from Sept. 30 to Dec. 30, and the new reauthorization deadline to Dec. 8.

In the second quarter, the usual entities lobbying on the program, mainly representatives of the insurance industry, were joined by a crowd of new or long-absent filers, close to a quarter of which were “banks and other non-insurance financial interests,” according to a Bloomberg BNA analysis. In the third quarter of 2017, as Hurricanes Irma and Harvey barreled into the Southeast and the reauthorization deadline approached, many of those financial interests were back, and for good reason. The NFIP, which requires homeowners with federally-backed mortgages in certain high-risk flood zones to purchase flood insurance and subsidizes about a fifth of those otherwise potentially cost-prohibitive insurance policies, is one of the last remaining barriers to a disaster for the high-value coastal real estate market.

Making matters worse, compliance rates for homeowners in flood-prone areas who are required to get insurance are dangerously low, leaving the borrowers at risk of major losses and leaving the banks liable for penalties for failing to enforce the insurance mandate — something many financial institutions and groups would like changed.

Bank of America Corp., which entered the fray this year after previously explicitly lobbying on the program back in 2012, reported holding “discussions related to the reauthorization of the National Flood Insurance Program” with both houses of Congress, according to federal lobbying documents. JPMorgan Chase & Co., which until the second quarter of 2017 hadn't named the NFIP in its lobbying forms since early 2013, said in a third quarter filing that it advocated for “reauthorization of the National Flood Insurance Program” before Congress, the White House and the office of Vice President Mike Pence. Until the second quarter of 2017, Wells Fargo & Co. had named the program only once in its filings, in 2016; in forms for the second and third quarters of this year, it named “issues pertaining to the reauthorization of the National Flood Insurance Program” and a related bill. In the same two quarters, Citigroup Inc., which appeared to have not expressly lobbied on the program before, reported pushing for “NFIP reauthorization.”

The Independent Community Bankers of America — a trade group that, until the second quarter of this year, hadn’t specifically lobbied on the program since mid-2015 — advocated for its interests in a litany of flood insurance bills, including the National Flood Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2017, before Congress and various federal agencies during the three months that ended in September, according to its third-quarter filing. The list goes on.

The banks aren’t alone. They’re part of a chorus of voices advocating for reform of a program that transfers much of the cost of insuring against the ballooning risk of catastrophic flood damage to taxpayers. And, like homeowners on the coasts, banks have a lot to lose with the loss of the NFIP.

Although only a fifth of NFIP policyholders received insurance premium subsidies in 2013, those policyholders faced annual premium increases of between 18 and 25 percent, depending on the type of borrower. The change was a result of the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012, which extended NFIP while seeking to adjust the program’s subsidies so that they might more accurately reflect flood risk. By redrawing the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s flood maps, it also “grandfathered” some property owners into higher-risk zones with new flood protection requirements and premium rates, prompting immediate backlash.

A Boston woman, for example, saw her annual premium jump from $3,000 to $68,000, because her home wasn’t elevated far enough above high tide. In a 2013 op-ed for his local paper, one Louisiana resident called the redrawing of maps and subsequent premium spikes “an illegal taking of property” complete with a “lack of due process.” In 2014, when lobbying on the NFIP also increased significantly, Congress repealed portions of Biggert-Waters.

Total coverage from NFIP rose from $50 billion in 1978 to a peak of $1.3 trillion in 2013, down slightly to $1.25 trillion last year, according to data from FEMA. Over the same period, the number of policies has grown from 1.4 million to nearly 5.1 million — down from a high of 5.7 million in 2009 — according to the agency. In July, the most recent month for which FEMA has NFIP coverage statistics, the total coverage stood at $1.23 trillion, with more than 4.9 million policies. That translates to plenty of mortgages spread among major lenders like Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Citi and JPMorgan Chase, all of which paid lobbyists to monitor or advocate for changes or reauthorization of NFIP in the second and third quarters of 2017.

‘Millions And Even Billions Of Dollars Of Collateral At Risk’

To banks, a loss of government-subsidized flood insurance in a high-risk area, coupled with a destructive hurricane, is “probably a rounding error in their bottom line,” J. Scott Holladay, an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville who has studied the economics of NFIP, told International Business Times. Still, given the sheer number of policies covered by NFIP and the widespread, simultaneous destruction that comes with increasingly frequent storms, he said, banks certainly have reason to worry about collateral for interest-earning mortgages they service. Small community banks and local branches of big banks in flood-prone municipalities are especially vulnerable, he noted.

“They’re exposed to risk because they have millions and even billions of dollars in collateral at risk,” Holladay said. And since “a whole neighborhood could be wiped out, … the risks are really concentrated. Community banks in those areas could see a big loss.”

That potential loss is made bigger, he said, by the disproportionately high values of NFIP-subsidized coastal homes. Their reduced insurance premiums, a far leap from accurately representing the risk of flood damage, are actually artificially boosting their values, research has shown.

In a 2007 report, the Congressional Budget Office found that coastal properties whose flood insurance had been subsidized by the NFIP exhibited market values far higher than the national average, a disparity the CBO attributed to the general desirability of a waterfront home. But, compared to coastal and inland homes in general, the value difference was magnified among properties with NFIP subsidies, with coastal homes having a average value 86 percent higher than their inland counterparts. Many of the waterfront properties, the study noted, were “nonprincipal residences,” or vacation homes. And the fact of being a stone’s throw from the shore wasn’t the only thing lifting their values.

“Some or all of the value of the subsidy available on coverage for a given property is likely to be capitalized into the property’s value,” the CBO report said. “Thus, when a subsidized property is sold, the buyer essentially pays for some or all of the subsidy’s value upfront, through a higher purchase price, thus reducing or eliminating the net gain.”

Those property owners may have further benefited from a negative relationship between the values of homes with NFIP-subsidized insurance and their premium payments — or, conversely, a positive relationship between the price tag on those homes and the sizes of their subsidies — as described in a 2015 University of Massachusetts - Dartmouth study of the program.

“What we ultimately have with coastal properties is, on average, high market value homes that are increasingly finding themselves in risky situations,” Chad McGuire, a University of Massachusetts - Dartmouth public policy professor and one of the authors of the study, noted. If the mortgage issuer finds itself “overexposed” to those risks, he added, ensuring the NFIP’s continuity becomes “a measure of protection.”

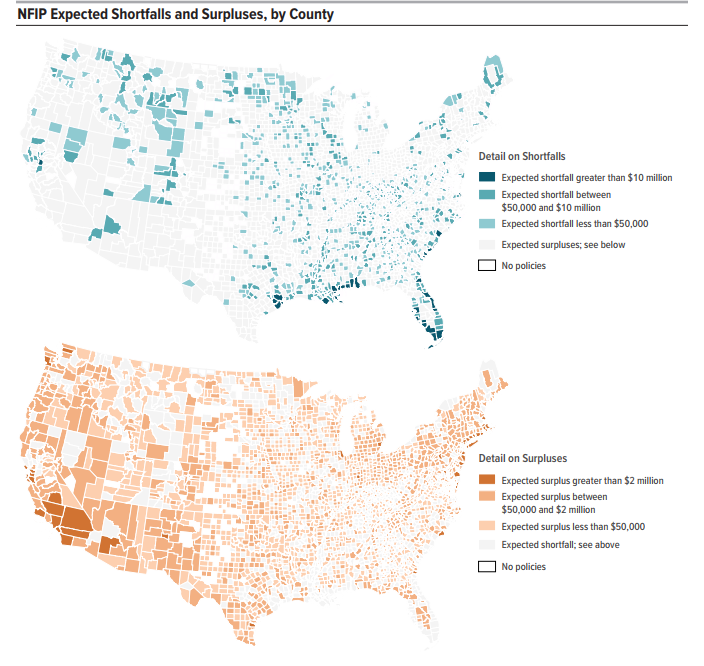

Ten years after the aforementioned CBO report, the office revisited the program, and found that those relatively expensive coastal homes were responsible for a disproportionate amount of the NFIP’s budget shortfalls as well. The program suffered a $1.4 billion shortfall in 2016, according to a new CBO report released in September. Yet premiums from inland properties amounted to a surplus for those areas over the same period; by contrast, premiums minus claims in coastal properties, which constituted 10 percent of counties covered by NFIP but three-quarters of its policies, resulted in a $1.5 billion loss.

Banks, insurers and their representative groups on Capitol Hill are advocating for FEMA to make it easier for private insurers to offer coverage for lower-risk zones currently covered by NFIP as an alternative to homeowners. But as the 2017 CBO report noted, “if the private market was able to compete for the NFIP’s lower-cost policies — that is, those for which the NFIP’s premiums are (or would be) large relative to their expected claims — the NFIP could be left with relatively high-cost policies.”

Take away the subsidies inflating the values of coastal homes and the government safety net helping to insure their losses, and the next Harvey or Irma could be a sobering prospect for mortgage lenders. That risk is spread outward when banks transfer mortgages to other banks or sell federally-backed mortgages to government-sponsored enterprises, or GSEs, like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which then transfer them to the secondary market as investments.

“They immediately sell the mortgage to Fannie and Freddie. They shift the risk,” said McGuire, pointing out that the banks get paid interest for servicing the mortgage. “Who bails out Fannie and Freddie? The taxpayers.”

When asked about the allocations of their mortgages in high flood risk areas and those with NFIP-subsidized insurance, JPMorgan, Citigroup and Bank of America, some of the largest mortgage servicers lobbying the federal government on the NFIP, declined to answer. Tom Goyda, a Wells Fargo spokesman, said approximately 4 percent of the $1.6 trillion in residential mortgages serviced by the bank were for properties in high-risk areas where FEMA required flood insurance as part of the NFIP, but was unable to disclose the portion sold to GSEs or transferred elsewhere.

‘Not A Lot Of Compliance’ Despite Flood Insurance Requirement For Risky Borrowers

Whether the NFIP is reauthorized by the new December deadline or not, the banks still face substantial risk in the event of a hurricane, because compliance with FEMA’s mandate that homeowners in especially flood-prone areas buy flood insurance is just slightly over half as of August 2015, according to an agency presentation. Florida and Texas hovered slightly above the national average, each with around 57 percent of residents in flood risk zones complying.

Using data spanning the period between 2000 and 2009, a 2011 study from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School pegged the compliance rate at a higher 61 percent, but found that homeowners in risky zones were increasingly likely to let their coverage lapse as the years went by.

“Of the 841,000 new policies entering the NFIP in 2001, only 73.2 percent… were still in force one year later,” the researchers wrote. “After two years, only 49.5 percent of the original 2001 policies were still in place. By 2009... only 19.6 percent of them were still in place.”

The study authors also expressed concern that “mortgages are often transferred to other banks (and then to the secondary market) in non-flood-prone regions of the country, where there is less awareness of either the flood risk or the requirement that homeowners may be required to have this coverage.”

The mortgage lenders and GSEs are responsible for keeping track of this compliance, and the lenders can be penalized if they let the borrowers go uninsured. But Carolyn Kousky, the director of policy research and engagement at Wharton’s Risk Center, said her impression was that the banks hadn’t faced many fines, despite “most estimates” indicating that “there’s not a lot of compliance.”

“As mortgages are bought and sold, there’s not a lot of enforcement through the life of the mortgage,” Kousky said. She added that, although flood-related defaults aren’t incredibly high, “a lot of people seem to be scratching their heads about why banks aren’t that concerned with enforcing disaster insurance.”

Lloyd Dixon, the director of the RAND Center for Catastrophic Risk Management and Compensation, said financial institutions have a “thorough process” for making sure their borrowers comply, and said larger banks were better at it than smaller ones. But ultimately, he said, the stakes for monitoring compliance are high.

“If there isn’t flood insurance and big losses happen, there is a fallout that could be bad for the banks and their equities and collateral,” Dixon said.

Financial industry groups, such as the American Bankers Association, want to both strengthen the insurance mandate for residents in high-risk zones and remove some of the burden of enforcing that mandate from the banks’ shoulders.

Goyda, of Wells Fargo, said the bank has “a very thorough process to assess when insurance is required, to determine if coverage is in place and to ensure that coverage is obtained, when necessary.” GSEs have also said their mortgage loans have required coverage. JPMorgan, Citi and Bank of America did not respond to questions about their high-risk borrowers’ compliance with the flood insurance mandate.

As McGuire, the University of Massachusetts professor, noted, “shoring up this enforcement can be beneficial when it ensures NFIP coverage exists,” as “with NFIP coverage there is a clear opportunity for federal disaster relief funds as well.”

“So that means [there is] opportunity for insurance and disaster coverage to mitigate risk of loss,” he said. “This makes the benefit-cost calculation move toward a net benefit, from a business decision standpoint.”

A New Mortgage Crisis On The Coasts

Compounding all of these problems is the fact that flood risks aren’t going away. As global temperatures and sea levels continue to rise, destructive storms will only grow more damaging and frequent, as they already have been. Which leads to another problem for banks that service mortgages for waterfront real estate: Holding property in those high-risk areas is becoming virtually untenable, and as those homeowners make their exodus — as is already the case — the values of those properties will drop precipitously. In fact, many have warned of an impending housing market crash on the nation’s coasts. And the only thing standing in the way of that potential mortgage crisis may just be the NFIP.

While median home prices in low-risk zones have risen 29.7 percent in the past 10 years, those of homes in high-risk zones have fallen 4.4 percent over the same timeframe, the New York Times reported, in a story ominously titled “Perils of Climate Change Could Swamp Coastal Real Estate.” That wouldn’t be such bad news for mortgage lenders if coastal real estate represented a small fraction of total property value, but that’s not the case. More than a third of total taxable property value in the U.S., worth $1.4 trillion, sits an eighth of a mile or less from a saltwater beach, according to a Reuters analysis.

“The risk will rise as sea levels rise, and when that happens, you’d expect your property value to fall,” said Dixon, of the RAND Center. Even for those who do comply with FEMA’s insurance requirement, he said, the policyholder can collect the claim and leave, but even if the structure is gone or uninhabitable, “the property stays there,” and may even hold negative value, depending on the damage. “At some point, the property becomes worthless.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.