Relics Of Its Golden Past, Mosul's Trains Left To Rust

Nearly a century ago, Iraqis and Westerners stood here with tickets to Berlin, Istanbul or Venice. Today, the rusting tracks and overturned carriages of Mosul's train station betray the city's isolation.

Battered by sanctions against the old regime of Saddam Hussein, back-to-back conflicts and little investment, the once grandiose train station in the Iraqi city's western half is a shadow of its former self.

The first train rumbled into Mosul station in 1940 from the capital Baghdad, then roared out to Istanbul to join the celebrated Orient Express -- taking passengers as far as Paris, 4,400 kilometres (2,730 miles) away.

In the 1950s, novelist Agatha Christie arrived at Mosul station, which later featured in her detective stories.

Mosul was an essential stop in the Iraqi Republic Railway system, which for decades linked Baghdad to 72 locations every day via 2,000 kilometres of tracks.

"Every day, there were either passenger trains or cargo trains," recalled Amer Abdallah, 47, who worked as a train conductor in Mosul up until a decade ago, when the last train pulled out of town.

At the bombed-out station, the father of five caressed a rusting locomotive, his face contorting into a grimace.

"My darling," he said, his nickname for this train engine.

Abdallah and others have fond memories of trips west to Syria or south to Basra, bridging cities and peoples that now feel brutally blocked off from one another.

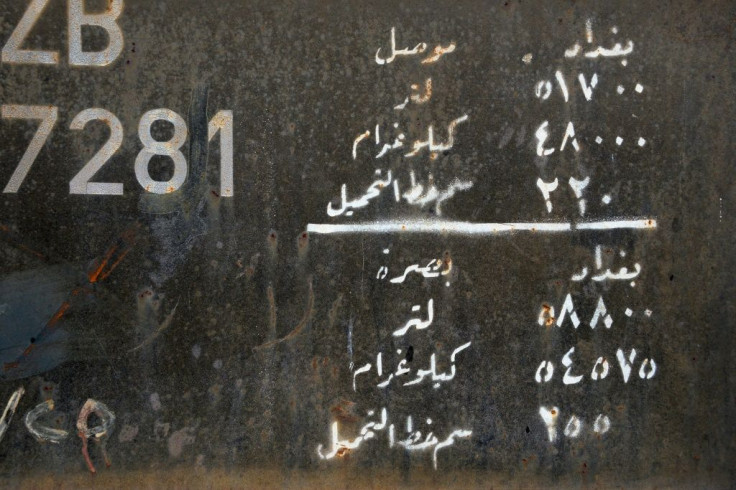

"For just 1,000 or 2,000 dinars (around $1), we could go to Baghdad or elsewhere in Iraq," said Ali Ogla, a father of seven who used to take the train regularly.

"It was a comfortable way of travelling for sick or handicapped people. When it comes to the cargo, we'd be sure it would arrive on time and in good shape," Ogla said.

The station was more than just a transport hub: it was Mosul's economic engine and a source of national pride.

"The station hosted one of Mosul's oldest hotels, coffee shops, gardens, a garage for horse-drawn carriages and later, for cars," said railway engineer Mohammed Abdelaziz.

Railway and station employees, businessmen, restaurant and cafe owners and taxi drivers all made a living from the train traffic through Mosul, Abdelaziz said.

King Faisal II, toppled in the bloody coup of 1958, had his own reception room within the station.

Egyptian musical diva Umm Kulthum passed through it and in 1970, the station agreed to silence its bells and whistles during a concert by Lebanese singer Sabah.

But in the 1990s, crippling international sanctions made it hard to get parts to maintain the trains and in 2003, the US-led invasion opened the door to a wave of bombing then sectarian violence across the country.

Still, trains roared out of the Mosul station every week, either 400 kilometres south to Baghdad, west to Syria or north to the Turkish border city of Gaziantep.

On May 31, 2009, a truck bomb destroyed much of the station and in July 2010, the last train left Mosul on a one-way trip to Gaziantep.

But things got even worse: in June 2014, the Islamic State group overran the city and declared it the Iraqi capital of its so-called "caliphate".

The station, until then left rusting in the sun, became a battlefield.

"Eighty percent of it was destroyed," said Qahtan Loqman, deputy head of Iraq's northern railway.

Iraqi security forces won Mosul back in 2017 but reconstruction of the city has been slow, with thousands still waiting for compensation for homes destroyed in the fighting.

The state has been unable to rake in enough oil revenues to break even and has halted infrastructure investment.

"There is no money and no schedule to repair the complex," said Loqman.

Mosul was Baghdad's gateway to Turkey, and on to Europe.

Without this way station, the capital is now cut off from the north: trains from Baghdad only head to Fallujah further west, or Karbala and Basra.

Today, rust eats into the fading red, yellow and green paint of an overturned carriage, its cogs and axels spilling out onto the track as if it had been disemboweled.

Misshapen carriage doors hang off their hinges and the old columns on the platforms have been ripped apart by gunfire or tagged with black graffiti.

The intricate floral mosaics of the galleria have been blown to smithereens but part of the rose-coloured stone entrance is still standing, a tribute to a glorious past.

Nur Mohammad, a 37-year-old housewife, recalled walking through the doors with her grandmother almost a generation ago.

"I was 10 years old. We all left together: family, friends, neighbours. We watched the countryside pass by through the train windows," she said.

"Those were beautiful days. And I hope we'll find them again."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.