Remains Of Homo Naledi, An Early Human Who Coexisted With Homo Sapiens, Found In South African Cave

An extinct human species, the Homo naledi, shared space with modern humans as well as other hominins between 226,000 and 335,000 years ago. And archaeologists now know more about the newfound species, thanks to a new fossil find in South Africa.

The Rising Star subterranean cave system in the country yielded the largest known cache of fossils of older human species, first revealed in September 2015. In a series of papers published Tuesday in the journal eLife, scientists announced they had found more remains of the human relative in another chamber of the cave system. The new fossils are the remains of at least one juvenile and two adults, including a skull that is almost complete.

Read: Skull, Two-Legged Walking Evolved Together In Humans

John Hawks, an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who is the lead author of the paper describing the new fossils, commented on the new find in a statement Tuesday. He said the fact that the physical distance between the new discovery and the fossil finds last year lends support to the theory that Homo naledi cached their dead — behavior suggestive of intelligence and beginnings of culture.

The chamber where the new fossils were found has been named Lesedi, after a name in the Setswana language that means “light.” The other chamber, about 100 meters away, where fossils were found earlier, representing at 15 individuals of various ages, is called Dinaledi. Over 130 fossils have been retrieved so far from Lesedi Chamber, which is very difficult to access, requiring crawling, climbing and squeezing in pitch dark.

The chamber and its fossils were first discovered in 2013, when Dinaledi Chamber was being excavated. The child among the three newly discovered individuals is thought to be less than 5 years old, and was identified by bones of the head and the body. One of the adults was represented only by one jaw and leg bones.

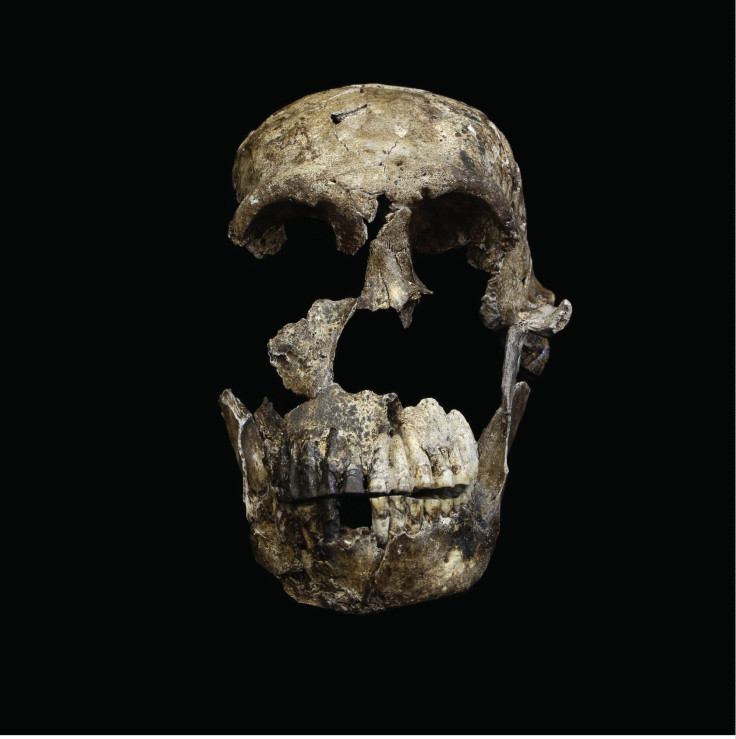

The third individual has been named “Neo” after the Sesotho word for “a gift.” The skeleton of Neo is “remarkably complete,” according to the statement, and its skull was reconstructed over hundreds of hours.

Peter Schmid from the universities of Witwatersrand and Zurich, who put together the fragile bones to create the skull, said in the statement: “We finally get a look at the face of Homo naledi.”

The skeleton of Neo is the most complete ever-discovered for a Homo naledi, and scientists now have more specimens of this extinct hominin species than any other, except Neanderthals.

Elaborating how the find has expanded our understanding of the species, Hawks said: “The ‘Neo’ skeleton has a complete collarbone and a near-complete femur, which help to confirm what we knew about the size and stature of Homo naledi, and that it was both an effective walker and climber. The vertebrae are just wonderfully preserved, and unique — they have a shape we’ve only seen in Neanderthals.”

Read: Big Brains In Primates Are Linked To Diet

Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist from the University of Witwatersrand and a senior author of the paper with Hawks, compared the Neo fossil favorably to Lucy — the name given to the fossil pieces of a female individual of the hominin species Australopithecus afarensis. Her skeleton is 40 percent complete.

“The skeleton of ‘Neo’ is one of the most complete ever discovered, technically more complete than the famous Lucy fossil given the preservation of the skull and mandible,” Berger said in the statement.

Caching of the dead in difficult-to-access underground chambers by Homo naledi has only one known parallel in the past that long ago, among Neanderthals.

Hawks said of the practice: “What is so provacative about Homo naledi is that these are creatures with brains one third the size of ours. This is clearly not a human, yet it seems to share a very deep aspect of behavior that we recognize, an enduring care for other individuals that continues after their deaths. It awes me that we may be seeing the deepest roots of human cultural practices.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.