Report On Fukushima Nuclear Disaster Says It Was Man-Made -- And Questions Japanese Culture

Japan's national soul-searching, catalyzed by last year's nuclear disaster, has not yet produced any new energy policy.

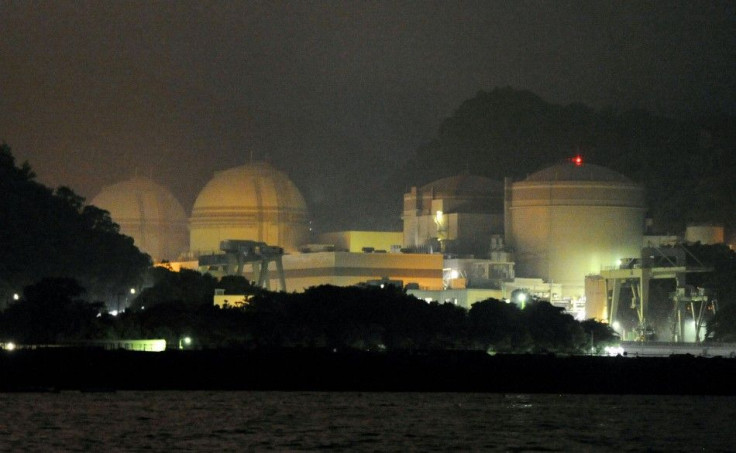

Amid widespread resentment and disapproval, the government has nevertheless managed to push through the restart of a major reactor in Western Japan. On Thursday, Reactor 3 of the Oi Nuclear Plant in Fukui Prefecture got the dubious honor of being the first reactor restarted after the March 2011 nuclear disaster in Fukushima precipitated a shutdown of nuclear plants across the country.

Activists are worried the move marks the first step down the road for eventually reintroducing nuclear energy extensively across Japan.

But on the same day, nuclear opponents also got new ammunition they can use against the government's policies.

The Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission, or NAIIC, the first independent commission ever launched by the Japanese Diet, has roundly condemned the Fukushima nuclear disaster not only as a man-made and avoidable occurrence; it has also labeled the failures that led to it as uniquely Japanese.

In a major half-year study, the NAIIC called the disaster a preventable one, caused ultimately by the collusion of a lackluster government tied to an opaque bureaucracy, deferent to business interests, within a general social and cultural climate that failed to call any of those parties into full account.

Betrayal Of The People

While the report considers the earthquake and tsunami as the proximate causes for the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, it blamed public-private betrayal of the people's safety as the primary factor that created the conditions allowing the disaster to be so catastrophic.

Although triggered by these cataclysmic events, the subsequent accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant cannot be regarded as a natural disaster, the NAICC noted. It was a profoundly man-made disaster -- that could and should have been foreseen and prevented. And its effects could have been mitigated by a more effective human response.

According to the report, the accident was the result of collusion between the government, the regulators and TEPCO [Tokyo Electric Power Company, the company operating the plant] and the lack of governance by said parties. They effectively betrayed the nation's right to be safe from nuclear accidents. Therefore, we conclude that the accident was clearly 'man-made.'

The NAIIC investigation started in December 2011. It has built its case on interviews and hearings with experts and directly involved personnel, spending more than 900 hours with 1,167 people in total. The 10-member team, chaired by Kiyoshi Kurokawa, a fellow of Japan's National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, conducted visits to nuclear sites and facilities across Japan, including the Fukushima Daiichi (No. 1) Nuclear Plant.

NAIIC claims that the government and TEPCO have been aware of the dangers of a tsunami hitting the site since 2006. The government failed to act in the interim to impose new safety standards on the plant and TEPCO.

Two major regulators in the country -- the Nuclear Industrial Safety Agency, a division of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, the government's powerful bureaucratic arm for regulating and promoting industry, scientific development and economic growth; and the Nuclear Safety Commission, the cabinet's nuclear investigator -- both failed to properly enforce new regulations on TEPCO.

In instances where NISA knew TEPCO was not prepared to take action on its own to lessen or mitigate the risk of seismic environmental disasters, it should have required strict site reinforcement. Instead, it left TEPCO to carry out such changes autonomously -- procedures which it in turn simply put off.

NAIIC claims that TEPCO did not carry out critical adjustments at the Fukushima plant, because it would have interfered with plant operations and weakened their stance in potential lawsuits. That was enough motivation for TEPCO to aggressively oppose new safety regulations and draw out negotiations with regulators.

Both nuclear regulators and operators failed to correctly develop the most basic safety requirements, such as assessing the probability of damage, preparing for containing collateral damage from such a disaster and developing evacuation plans for the public in the case of a serious radiation release.

Government Bungling

The same government entrusted to protect the people from the dangers of nuclear power came instead to protect the interests of the companies it was meant to scrutinize.

No surprise then that as the disaster unfolded, agencies that should have established efficient and effective response mechanisms instead became caught in a web of confused command structures.

The NAIIC noted that the regulators and other responsible agencies did not function correctly. The boundaries defining the roles and responsibilities of the parties involved were problematic, due to their ambiguity. None, therefore, were effective in preventing or limiting the consequential damage.

NISA, which should have played a leading role in disaster response, failed to take on responsibilities mandated since 1999. The office of ex-Prime Minister Naoto Kan waited too long to declare a state of emergency and later interjected itself into the chain of command, creating further unnecessary complexity and misunderstandings. The failure of regulators to convey information to the government led to a loss of faith in their abilities. TEPCO, then chaired by Masataka Shimizu, which should have readily provided information on their activities during the crisis, instead took on a mindset of avoiding responsibility.

Whether those inefficiencies directly cost lives is difficult to discern, but it certainly prevented accurate and timely information from flowing to local residents, those directly affected and closest in proximity to the disaster area.

When the March 11 nighttime evacuation of the 3 kilometer [2 mile] area around the plant was ordered, NAIIC says that only 20 percent of the residents of the town hosting the plant knew about the accident. A majority of residents 10 kilometers [6 miles] around the plant only knew about the nuclear accident some 12 hours after it began and received no follow-up information or directions when an evacuation was ordered.

Future Dangers

NAIIC also questioned the present view of the disaster as chiefly caused by the tsunami and believes that this interpretation benefits TEPCO and was knowingly propagated by the company to improve its image.

The commission notes that TEPCO was too quick to cite the tsunami as the cause of the nuclear accident and deny that the earthquake caused any damage. ... This is an attempt to avoid responsibility by putting all the blame on the unexpected (the tsunami), as they wrote in their midterm report, and not on the more foreseeable earthquake.

In fact, NAIIC believes that the earthquake's disruption of electricity to the nuclear station, cutting off all outside power, was the first part of a double knockout blow that eventually prevented the critical cool-down systems for the reactor cores from being started. It does, however, admit that conclusive determination of what damage the earthquake truly caused to the reactors themselves requires closer investigation in the future.

But the NAIIC conclusion to further consider earthquakes rather than tsunamis alone as endangering nuclear plants calls into questions Japan's entire nuclear industry and whether it even has a place within the country. After all, the whole country is effectively in danger of major seismic activity. If broadly accepted, the viewpoint will further degrade the government's political capital as efforts to restart reactors around the country continue.

How this point was overlooked for decades remains a peculiarity in itself but is largely rooted in the pro-nuclear culture that pervaded Japanese society in the past.

As oil shocks hit the country in the 1970s, fears of energy insecurity and a push for self-reliance gave a major boost for the nuclear industry.

NAIIC Chairman Kurosawa noted in the report that the mentality of the time was part of a single-minded determination that drove Japan's postwar economic miracle. With such a powerful mandate, nuclear power became an unstoppable force, immune to scrutiny by civil society.

As a result, its regulation was entrusted to the same government bureaucracy responsible for its promotion, he added.

'Made In Japan'

But the report's most damning and controversial words may come from Kurosawa's determination to link the disaster with Japan's own culture.

What must be admitted -- very painfully -- is that this was a disaster 'Made in Japan,' he wrote.

Its fundamental causes are to be found in the ingrained conventions of Japanese culture: our reflexive obedience; our reluctance to question authority; our devotion to 'sticking with the program'; our groupism; and our insularity, lamented Kurosawa.

Those words are a blow not only to one particular industry, but to a long-established way of thinking and acting in an entire nation. In the past, the self-assurance and conviction of Japan's technological prowess led many citizens to take for granted that the country was in no danger from the poor industrial standards or unsafe practices troubling its neighbors and countries elsewhere around the world.

The nuclear disaster has now shaken much of that former faith, and it may have larger implications. As Kurosawa noted, Each of us should reflect on our responsibility as individuals in a democratic society.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.