Rice Prices Are Rising In Philippines After Price Cap Lifted; Food Crisis Worries Loom

KEY POINTS

- Higher-rated grains have started going back to their prices before the price cap was implemented

- Food-related issues can turn into "a much broader crisis" like the 2008 global rice prices surge: ASPI's Genevieve Donnellon-May

- Marcos Jr. promised during his campaign that the country will see rice prices drop to 20 pesos ($0.35) per kilo

Just a week after Philippine President Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr. lifted the rice price cap, prices in the country started trending up, reflecting the "complex challenges" that some Southeast Asian governments face in balancing supply of the Asian staple.

The Marcos administration lifted a month-long rice price ceiling on Oct. 5 after his government set the maximum retail price of regular milled rice at 41 pesos ($0.72) per kilogram (2.2 pounds) and 45 pesos ($0.79) for well-milled rice. While the temporary solution appears to have helped contain rice prices in the country from swelling further, it seems to not have helped keep rice inflation in check.

The country's rice inflation in September surged 17.9% on the year, marking its highest increase in the past 14 years. And rice prices appear to be going back to their earlier levels, particularly higher-rated grains.

In the week before the price ceiling was announced, local regular milled rice had a weekly average price of 51.22 pesos ($0.90) per kilogram, according to data from the Philippine Department of Agriculture (DA). The day before the price cap was implemented, regular milled rice was priced between 52 pesos and 55 pesos, the well-milled type started at 48 pesos ($0.84) to 56 pesos ($0.98), premium grains were priced between 50 and 60 pesos ($1.05), and special rice had a price tag of up to 62 pesos ($1.09) per kilogram.

In the last week of the price cap's implementation, local regular milled rice had a weekly average price of 41.22 pesos while well-milled rice was at 45.21 pesos.

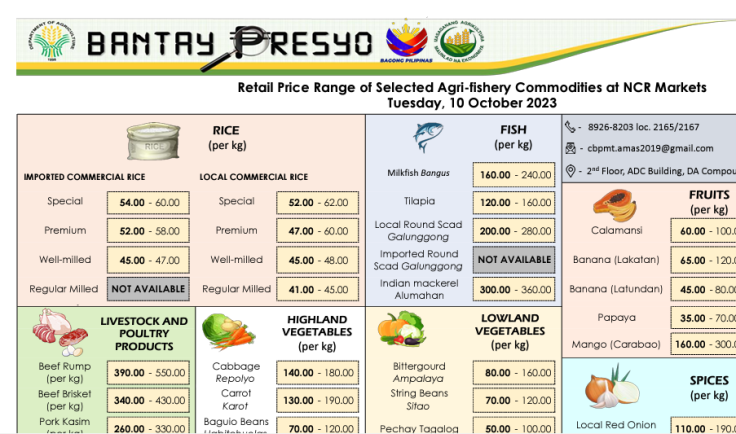

As of Oct. 10, local regular milled rice in markets around the National Capital Region (NCR) were priced anywhere between 41 pesos and 45 pesos, as per the DA's daily Bantay Presyo (Price Watch) report. Well-milled rice started at 45 to 48 pesos, premium rice prices started at 47 to 60 pesos, and special grains were priced between 52 and 62 pesos.

With rice prices apparently pivoting to the same levels before Manila's price cap, it "remains possible" that the country's rice prices issue could affect Southeast Asian and even Asian trade, Genevieve Donnellon-May, Asia geopolitics expert and research associate at global business and policy think tank the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI), told International Business Times.

She noted that unlike other commodities, food can be quite disruptive in the global realm. "Small disruptions turn into a bigger disruption and then a much broader crisis like what we saw in 2008," she said.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) said in a 2012 report that one of the key drivers of the dramatic surge in rice prices in 2008 was "panic buying" in some of the world's major rice importing countries – the Philippines being one of them. Rice prices were up by 117%-149% during Q1 2008. Nearly a billion people were driven to poverty during that rice crisis.

The current situation in the Philippines only "reflects the complex challenges" that some Southeast Asian and Asian governments face "when it comes to balancing the supply-demand of rice," Donnellon-May said. After all, 90% of the world's rice is grown in Asia.

As rice and other food prices spike across the region, governments may be likely tempted to implement more policies, such as export restrictions or hoarding, which could ultimately have a ripple effect on global prices.

There is no quick fix to the multifaceted issues that the Philippines is faced with and the Marcos administration is "in a tough situation," Donnellon-May pointed out. Aside from thinking of ways to prevent domestic rice prices from spiking, the government also has to find the right prices that will satisfy both producers and consumers.

The DA reassured the public over the weekend that the country has enough rice supply to last until early 2024 as farmers are expected to make a bumper harvest – one that produces unusually productive yields – from October through November.

Donnellon-May, who is also a geopolitical consultant and global strategy adviser, said the Philippine government can explore partnerships between farmers and local government units to help minimize the pressures on rice prices.

Marcos Jr. promised during his presidential campaign that after he wins, there will be cheap rice at 20 pesos ($0.35) per kilogram in the country. More than a week after he implemented the price ceiling, he said there was always a chance to achieve his campaign promise of cheap rice prices.

Whether that low price level can be achieved will be known only when the harvest season is over.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.