Road To Rio: Brazil Offers Syrian Refugees A New Home, But The Economy Puts Their Latin American Future In Question

Hayat Houbbi stuck out when she started studying accounting at a university in the Brazilian megacity of São Paulo. Her colorful hijab head scarves drew questions and curious stares from fellow students. “Are you a member of ISIS?” she was asked several times. It was the first time many of them had ever met a practicing Muslim, much less someone who had escaped the war in Syria.

Houbbi and her family are among thousands of Syrians who have arrived in Brazil in recent years fleeing a five-year civil war. With neighboring countries in the Middle East feeling the weight of millions of refugees, Houbbi and her family ruled out undertaking the dangerous journey to Europe and began to search for a legal option in a country not overwhelmed by war survivors. Within a week of applying for Brazil’s special humanitarian visa program, the family was approved.

“We don’t know anyone here in Brazil, and the language is very strange for us, but it was the only option.”

“When wars start, without food, without medication, electricity, water, without internet and phone, and you have the fear of being killed at any moment, you will not stay. When you hear army aircraft every ... hour, you will not stay,” said Houbbi, 22, who now lives with eight relatives in a small apartment in São Paulo. “Brazil was really my only option. We don’t know anyone here in Brazil, and the language is very strange for us, but it was the only option.”

With the world focused on Brazil ahead of the Olympic Games this summer, a small but growing number of Syrian refugees in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo are confronting the dual challenges of learning Portuguese and finding employment amid the country's worst recession in decades. Brazil’s unemployment rate has hit double digits, rising from 6.5 percent at the end of 2014 to 10.2 percent in 2016. The country's political establishment is in turmoil, with President Dilma Rousseff fighting for survival against the looming threat of impeachment. And as the Brazilian government talks with the European Union about taking in more refugees from Syria, those already in Brazil are questioning whether they can build successful and stable futures in South America's largest nation — lives comparable to the ones they had before the war.

Refugees continue to flee conflict-ridden and repressive states such as Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. But after more than 1 million refugees arrived in Europe last year, the 28-member European Union is eager to limit the number of new arrivals. Family reunifications in the EU are becoming more difficult, with courts increasingly backing rulings that sponsors must be able to support themselves as well as members of their families. The U.S., meanwhile, has fallen behind on its goal to accept 10,000 Syrian refugees. Only 1,285 have been resettled there so far this year.

All of these circumstances have made Brazil an attractive option for refugees who can afford the airfare. Among Latin American countries, Brazil has emerged as the regional leader, granting 8,474 special humanitarian visas for Syrians as of March, with 2,250 being granted asylum. The policy is set to remain in place until 2017, according to Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“The numbers are still small if compared with other countries', but the increase was significant in terms of the reality experienced by Brazil,” Liliana L. Jubilut, a professor at the Catholic University of Santos in São Paulo, who specializes in refugee law, said in an email to International Business Times. “This has stretched the government’s and civil society’s capacity in assisting and protecting refugees as the numbers grew enormously (a 930 percent increase from 2010 to 2013 and still growing), and the budgets and personnel stayed the same or were reduced.”

The International Olympic Committee has sought to focus the world’s attention on the plight of refugees worldwide with the historic creation this year of an Olympic team of five to 10 members comprising solely refugees. Team Refugee Olympic Athletes, as it has been dubbed, will march behind the Olympic flag at the opening ceremonies in less than 100 days in Rio. Last week, Ibrahim al-Hussein, a Syrian refugee living in Greece, carried the Olympic torch through a refugee camp in Athens. An active athlete, Hussein lost part of his leg during a bombing.

"I am carrying the flame for myself but also for Syrians, for refugees everywhere, for Greece, for sports, for my swimming and basketball teams," he told Agence France-Presse.

But the summer Olympics in Rio have also brought up questions about government priorities and spending on social services that are badly needed in a country that has no official support structure for helping refugees integrate into society. The Olympic Games come with a price tag of $11 billion, and the Brazilian government is covering approximately 40 percent of the cost. Five of the private companies helping to pay the rest of the bill are under investigation in connection to the Petrobras corruption scandal, an elaborate bribery scheme involving the government-controlled oil giant. In comparison, Brazil is planning to spend approximately $2.3 million on expanding the country’s network of public centers for refugees in 2016.

Amid the refugee crisis, European nations have seen the rise of right-wing anti-immigration groups; politicians in the United States have raised concerns over possible links between terrorism and refugees, with lawmakers demanding complicated screening processes that can take years to complete. Some cases of xenophobia and racism have been reported in Brazilian media, but the country has largely avoided a heated debate on whether to accept refugees. Brazilian authorities, with training from the United Nations, have expedited the screening process for refugees entering their country.

“I like Brazil, but it’s difficult to live here. It’s difficult to live here for Brazilians.”

“Brazilian society offers a key advantage compared to other European societies. Almost everyone is an immigrant in Brazil,” said Oliver Stuenkel, a professor of international relations at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation in São Paulo. “The cultural barriers children face in school are very limited, and I think the number of successful people first and second generation in Brazilian society is very high.”

While Brazil's economy enjoyed high growth during the 2000s, it contracted by 3.8 percent in 2015 and could contract by another 3.8 percent in 2016 amid falling global commodity prices and lower foreign investment. The recession has stalled most corners of the Brazilian economy, including the manufacturing and service sectors — areas where immigrants are often able to find their first jobs. The country’s low income and emerging middle-class populations have also been hit particularly hard. At the same time, a growing political scandal over the country's mismanaged finances could see Rousseff forced from office in the coming weeks.

“It’s a very hard moment for anyone who is looking to immigrate to Brazil and find a job,” said Monica de Bolle, a nonresident senior fellow who specializes in Brazil’s economy at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. “With this very tragic situation in the economy, it’s hard for everybody and particularly hard for those looking to Brazil as an opportunity. It’s currently not offering anything.”

Syrians in Brazil also must adjust to significant cultural differences in the world’s largest Catholic nation. Casual views on dress and relationships between men and women, along with the high crime rates in major cities, have come as surprises. Houbbi, for example, was taken aback when a woman hugged and kissed her on the street welcoming her to the neighborhood, a level of familiarity unheard of among strangers in Syria, especially practicing Muslims.

Brazilian Minister of Foreign Affairs Mauro Vieira said in a February speech Brazil was home to the largest Syrian diaspora in the world, with 4 million Brazilians of Syrian descent offering a connection for new immigrants. Brazil’s 2010 census showed a total Muslim population of over 35,000, but the Federation of Muslim Associations in Brazil claims the number could be as high as 800,000 to 1.2 million practitioners. In 2015, the number of mosques and Islamic prayer rooms grew by 20 percent in São Paulo to a total count of 30, fueled by the wave of immigrants from Africa and the Middle East, as well as domestic conversion.

And that population could continue to expand. Brazil’s Ministry of Justice is in talks with Germany and the EU about the possibility of taking in more Syrian refugees. “The deal is still at its beginning, and there is no date to be finalized,” a spokesman from the ministry told IBT by email.

Despite Brazil’s rising unemployment rate and uncertain political future, economists and political analysts said the country, with over 200 million people boasting the world's seventh-largest economy, is well-positioned to take in more refugees.

“Our labor market is really big. There are millions and millions of workers, so 2,000, 4,000 or 6,000 refugees would not be a big deal for the Brazilian economy,” said Rudi Rocha, a professor of economics at the Institute of Economics at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Brazil established special humanitarian visas in 2010 to help Haitians who were fleeing after their country’s devastating earthquake. Brazilian consulates in the Middle East began issuing special visas for Syrians and those affected by the civil war in 2013, the United Nations Refugee Agency said.

The special humanitarian visas waive traditional requirements, allowing people to travel to Brazil and then claim refugee status. Most importantly for refugees, from the moment they declare themselves to be asylum-seekers they can begin working and their children can begin attending school — an arrangement that is not offered in most countries.

“We have 200 million inhabitants, and the number of people from abroad is very small, so the potential political backlash of providing a couple of thousand of humanitarian visas is very, very small,” Stuenkel said. “For Brazil, it’s a cheap way to gain political credit abroad.”

“For Brazil, it’s a cheap way to gain political credit abroad.”

Brazil does not offer the all-encompassing government support refugees receive in many European nations. But flights to São Paulo from the Middle East run as low as $600, compared with the more than $3,000 a person most smugglers charge for dangerous sea journeys into Europe.

Houbbi’s father and brother bought plane tickets for approximately $800 apiece and headed to Brazil ahead of the rest of the family in November 2014. When they landed in São Paulo, no one was there to greet them or offer assistance. They grabbed a cab to a $20-a-night hotel they would call home for the next month. The next morning they set out in search of neighborhoods where they had heard they could find an Arabic speaker to help them fill out paperwork needed to register with the federal police.

“The government here only gives you a visa, and it’s all on you,” Houbbi said.

Houbbi, her mother and three brothers flew to Brazil in December 2015. By then, her father had found a small apartment for the family in the Tatuapé neighborhood, an area known for its industrial buildings and immigrant population. The well-off family had $4,000 in savings to help them start their lives anew in Brazil. Houbbi was surprised to see to homeless people on the streets of São Paulo, something she never saw in her native city of fewer than 3 million.

Ahead of the Olympic Games, Brazil has stepped up security with controversial “cleaning the streets” tactics that involve removing homeless people. Police killings in poor favela communities have surged ahead of the August games, with 11 people killed in April in Rio, Amnesty International reported last week.

Approximately 85,000 law enforcement officials are being sent to Rio for the games in the largest deployment seen for a single Brazilian city. Government officials have repeatedly promised they are prepared to deal with large-scale security to ensure a terror attack does not take place. Roughly $198 million has been spent on security so far, but security camera and fencing contracts were still pending, the Wall Street Journal reported in April.

Outside of Rio, people have yet to see a difference.

In Damascus, “you could walk in the streets like you could walk in your home," Houbbi said. “Every friend I have [in São Paulo], when I walk with him in the street when he sees my cell phone he says, ‘Oh, please take care.’ So it’s not safe, never.”

Houbbi, like many Syrian refugees in Brazil, was used to a high standard of living in Syria before the war. Her mother worked as a lawyer and her father as an electrical engineer. In Brazil, he recently opened a shop to fix air-conditioning units and refrigerators. Houbbi, meanwhile, has put her dreams of becoming a doctor on hold while studying accounting, a “universal” profession that could help her find a job anywhere in the world.

“The economy is very weak,” Houbbi said. “Everything is going to be much more expensive.”

Houbbi started a job as an administrative assistant at tax and accounting firm Gesplan and is now training as an assistant accountant while going to school. Out of 30 employees at the firm, two are refugees. It’s a conscious choice managing partner Mauro Andrade said he made as part of the company’s corporate social responsibility.

After taxes, Houbbi brings home about $30 more than Brazil's monthly minimum wage of $228.

“It’s difficult to live with this salary,” she said. “It’s hard because you don’t really have an option to make your life better. You have an option to keep it like it is or to go down.”

For Houbbi, going to mosque is an important part of her life in Brazil. She was quick to tell fellow students who asked about the Islamic State group, also known as ISIS, that the jihadists “are not Muslim and are not representing us.” She finds for the most part that Brazilians are simply curious about her religious beliefs. Her boss asked her if it was true that Muslims pray multiple times a day. After explaining the process to him, her office offered her a private room to use every day for prayer.

Houbbi is still considering her options. She has heard of other Syrians in Brazil traveling to the neighboring country of French Guiana, an overseas department of France. In French Guiana, Syrians can register as refugees and gain temporary residency and potentially receive humanitarian asylum in France — a long, circuitous path to a life in Europe. Houbbi sees a future in France that could find her completing her medical studies at one of its top universities.

“I have a life here, yes, it’s true, but I won’t let this period let me forget about my dream,” she said.

To help less wealthy arrivals get a start, the Brazilian government has allowed some Syrians who fall below an income threshold to enroll in the Bolsa Familia income assistance program. Over 160 Syrian families have enrolled and are receiving approximately $41 each per month. Brazil also provides some language courses, classes on starting businesses and funding to public centers for refugees, but the economic crisis has made providing services even to its own citizens more difficult.

While the Olympic Games are intended to showcase Brazil, officials have had to undertake cost-cutting measures such as trimming the number of game-time transport vehicles by 1,000, CNN reported. A key Rio subway line extension is still not finished, and officials say it won't be completed until July. Venues are 98 percent finished, but power outages and minor problems continue to plague the buildings.

With the government focused on the preparations and political chaos, most refugees have had to depend on networks of those who came before, as well as volunteer and non-profit groups, to help them navigate Brazil’s bureaucracy. For many Syrians, finding help from other Arabic speakers means landing in either São Paulo or Rio. In São Paulo, home to the largest Muslim community in Brazil, many refugees have settled in the Brás and Cambuci neighborhoods, where mosques offer a community.

“Where do I begin?” is the most common question Imani Zoghbi, director of communications at the Federation of Muslim Associations in Brazil, hears from refugees arriving in the country. “The hardest part for them is, they do not choose anything. They have to go where they can to live. They arrive somewhere that is better than they were, but it’s something completely new.”

The first step for many refugees is learning Portuguese.

“Integration is the most challenging thing for us,” United Nations refugee agency spokesman Luiz Fernando Godinho Santos said. “We have cultural barriers to be overcome. Language is the first one; it’s key not only for Syrian refugees but for all refugees living in Brazil to be functional with Portuguese.”

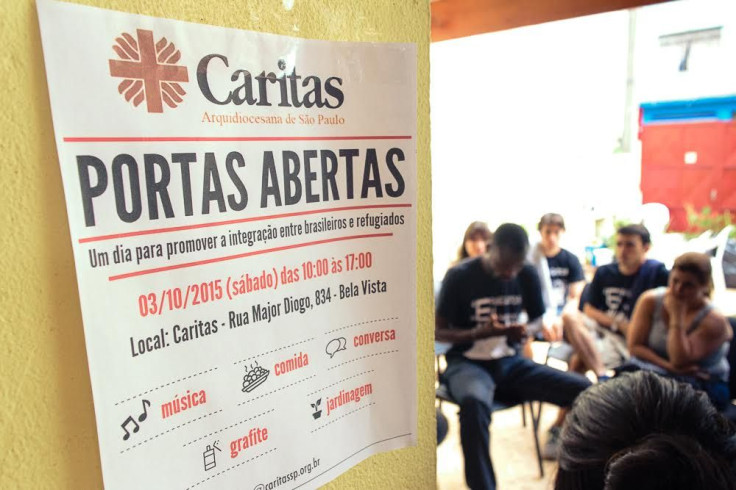

Another popular starting point for refugees in Brazil is the Centro de Referência para Refugiados, also known as Caritas, a social nonprofit tied to the Catholic Church that has been a United Nations partner since 1989 and holds the civil society seat with the Brazilian government’s National Committee for Refugees (Conare). But even Caritas is facing challenges without an institutionalized government system to help refugees.

“We don’t have a stable and equal system of reception for refugees,” Larissa Leite, protection coordinator at Caritas, said. “Syrians come mostly in families, so four, five, six, seven, 10 people in a group, which makes it more difficult to find shelter.”

After becoming conversant in Portuguese, many refugees turn to the Programa de Apoio para a Recolocação dos Refugiados, or the Support Program for the Replacement of Refugees. The volunteer program, run by the private consulting company Emdoc in São Paulo, helps refugees find permanent work by translating résumés into Portuguese and helping to match refugees with employers.

At first the program was helping refugees find service sector jobs as cleaners and receptionists. But as Syrians with higher education levels began arriving in increasing numbers after 2013 and applicants become more fluent in Portuguese, job prospects shifted to more highly qualified work as administrators and accountants, Vinicius Paris, the program’s volunteer manager, said. Over 60 percent of the people helped by the program have university degrees.

“The refugees who are here in Brazil are more prepared than Brazilian people. I see their CVs. They had really high positions in their country, and they are looking for any job because they need the money,” Paris said. “I don’t think this crisis we are passing now is going to be worse for them. I think the opposite because they have more qualifications, more education, more languages and everything. It’s going to be easier for them.”

Over 1,200 refugees so far have registered with the job help program, and 340 have found jobs. Kamal Daqa is one of those people.

Daqa, 34, knew he had to leave Syria after his pregnant wife was shot at when peering out of their apartment window in Damascus and members of his extended family were killed. An IT professional by training, he first took his wife and children to Egypt before heading to Brazil. Learning Portuguese has been one of the biggest hurdles for Daqa, who said his 4- and 10-year-old daughters have mastered the language at school, and his baby son is also quickly picking up the sounds of the language. Daqa took language classes through Caritas after arriving in Brazil.

Daqa spent a year working at a factory in production while continuing to improve his Portuguese. He eventually found work at an IT company as an administrator, but he has not yet been able to meet the standard of living he had in Syria before the war, when he earned $4,000 a month.

After two years in Brazil, Daqa is still taking evening Portuguese classes. Despite the difficult economic environment and the lower standard of living, Daqa is confident he made the right choice by leaving Egypt.

“Brazil is one of the countries which has perfect features. I’m very happy that I came to Brazil,” Daqa said on the phone after returning home from language class on a recent evening. “Living in Brazil is very hard for refugees because everyone should work and at night should study the language, because without studying the language they cannot improve their life. OK, there is some conflict here between the people and political things, but I think it’s temporary and it will become better.”

Living in Brazil also represented a rare opportunity to reunite his scattered family. His brother, Khaled, had ended up in a camp in Jordan with his own family, while their mother was living in the United Arab Emirates. Both are now living in Brazil.

“Brazil in this way gave more than Europe," Daqa said.

Daqa is hoping to have his computer science degree validated in Brazil in the next month, a challenge faced by many refugees and employers. He wants to study for master’s and doctorate degrees, and he still thinks about the possibility of pursuing degrees in the U.S. or Canada, where he can earn higher wages and use his English skills. He was accepted at a university in Canada, but his visa was never approved.

Brazil is rarely the first choice for Syrian refugees. Abdulbaset Jarour looked to both the U.S. and Canada for visas before deciding to try his luck with Brazil. When visas didn’t come through and neighboring countries flooded with Syrians offered few job prospects, Jarour, 26, left Damascus for Lebanon, where he paid $800 for a flight to Brazil two years ago. He had some savings to carry him through the first few months and also turned to Caritas for help.

The high school graduate had a good life back in Syria where he ran a cell phone and computer shop and made around $500 a month. He had a car and was able to enjoy going out with friends. These days, Jarour said he makes around $300 a month. He teaches Arabic part time and plays Arabic music at restaurants for a living. He continues to hope he will be able to move to Canada, where one of his sisters lives.

While Jarour has felt welcome in Brazil, he said Syria before the war felt like a safer place. The U.S. State Department described Syria as having a “low crime rate” in 2010, while Brazil’s 2015 crime rating was labeled “critical.” Jarour has been robbed twice on the streets of São Paulo, losing his cell phone and some money.

“I like Brazil, but it’s difficult to live here,” he said. "It’s difficult to live here for Brazilians. We are facing problems.”

In a hopeful sign, though, some observers say refugees could help solve Brazil's problems in the long run by offering the possibility for economic innovation. Economists point to foreign-born founders of successful American companies (like Google's Sergey Brin) and the disproportionate level of entrepreneurship by U.S. immigrants when making their arguments in the Brazilian press.

“One of Brazil’s major weaknesses is that is has a very low innovative capacity and its productivity is very, very low. I think we just need many, many more immigrants who could help revive the economy,” Stuenkel of the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, said. “I think the economic crisis in Brazil reduces the attractiveness of the country, but it actually increases the imperative to bring in more.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.