Road To Rio: Police Sweep Away ‘Street Children’ Ahead Of Brazil Olympics

With a faltering economy and an $11 billion investment at stake, Brazil wants nothing more than to stage a successful Olympic Games come August. The government is building new transportation and sports venues, hiring security guards and deploying soldiers, and sprucing up Rio de Janeiro’s most-visited areas. But “cleaning the streets,” as the project is euphemistically known, is not an effort to haul garbage but to sweep away homeless people and drug dealers — including the often drug-addicted children who live on the sidewalks of some of Rio’s wealthiest neighborhoods.

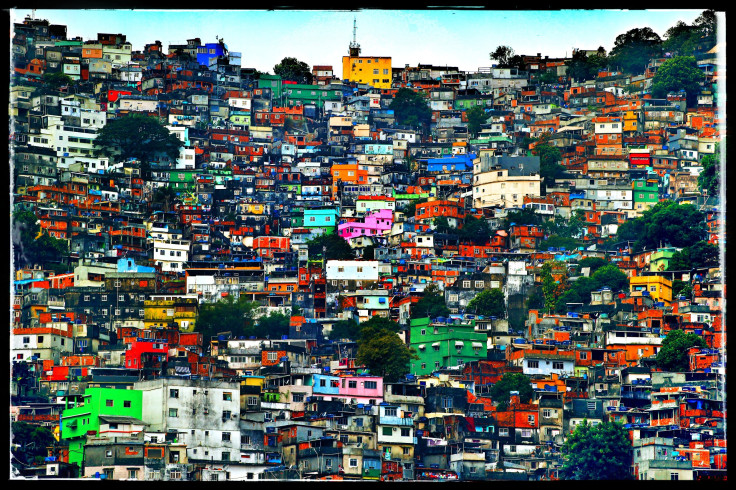

In the Copacabana and Maracanã areas, two of the neighborhoods preparing to host the Olympics, teenagers and children as young as 7 sleep by the roadside or beg for change. Boys often join gangs and sell drugs to survive while girls frequently turn to prostitution. Many smoke crack or sniff glue. Some live on the streets full time; others spend nights in the favelas, or nearby shantytowns.

It’s a side of Brazil that the government is hoping to hide from cameras this summer. As Rio prepares for the spotlight the Games will bring, advocates for homeless youth say children are being detained arbitrarily by police — or in some cases simply vanishing. They warn that the “cleanup” is likely to make life worse than ever for the thousands of children who have already been forced out of their homes by abuse or desperate poverty.

“They’re trying to give the image that Brazil is safe, that we are nice, that we are happy, that everything is all right. But it’s just a big lie.”

“The government will make a plan — a huge plan for the Olympic games — with the police, with the army, to clean the area, to let no poor person come in, to make sure no child is on the streets, to make everything beautiful,” said Daniel Medeiros, an advocate for street children who volunteers for Happy Child International, which operates a safe-house for girls in Recife. “They’re trying to give the image that Brazil is safe, that we are nice, that we are happy, that everything is all right. But it’s just a big lie.”

These are tough days for Brazil. The government is paralyzed by a major corruption scandal over allegations President Dilma Rousseff, who faces potential impeachment, manipulated numbers to hide an expanding budget deficit. The country has experienced its worst recession since the 1930s.

Just seven years ago, when Rio won the Olympic bid, the economy was booming and Brazil was billed a “country of the future.” The economy grew some 7.5 percent in 2010. During Rousseff’s first term (2011-14), the economy slowed with an average of 2.2 percent growth year-after-year. Last year, in her second term, gross domestic product shrank by 3.8 percent.

For the 2 1/2-week Games (followed by an 11-day Paralympics), Rio expects some 15,000 athletes, 45,000 volunteers, 93,000 staffers and 380,000 tourists to pour cash into local coffers. Despite some setbacks, including slow ticket sales, hotels are reportedly nearly booked and organizers say they are optimistic.

But the financial benefit of hosting a massive sporting event remains in dispute. The government spent around $11 billion on the World Cup in 2014 for new infrastructure and transportation, but the event failed to generate the lasting business growth or tourist interest that was predicted. A $550 million stadium in Brasilia that was constructed for the Cup was, a year later, being used as a parking lot. And while the number of foreigners searching for trips to Brazil shot up in the months ahead of the World Cup, it leveled back to normal pretty quickly thereafter. Still, tourism during the events brought in more than $1 billion, the Rio Times reported.

Government officials say the security preparations — including clearing out street kids — are critical to ensuring tourist safety. About 85,000 policemen and soldiers will be used for the games, about twice the number of security personnel present for the London Olympics in 2012. Rio authorities have said street children (there are an estimated 24,000 of them nationwide) are being detained for causing mischief.

The authorities concern is not unfounded. Last year, for example, local television showed gangs of youngsters swarming Rio’s famed Copacabana and Ipanema beaches, snatching cell phones, backpacks and other valuables, sending tourists fleeing in panic. Responding to the robberies, Copacabana residents set up “vigilante” groups and on at least one occasion, they stopped a city bus, smashed its windows and beat up a passenger they accused of stealing. A private security service made up of police officers recently sprang up in wealthy southern parts of the city, offering to clear neighborhoods of homeless people for about $250 per month.

Specifics about Rio’s police roundups remain scarce and the scale of official detentions unknown. The United Nations has expressed concern that street children are being taken to police stations “under unfounded suspicions and being arbitrarily placed in younger offenders institutions” without proper legal protections. Legal analysts say they are being treated as criminals without being convicted of any crimes. Brazilian jails are notoriously overcrowded, as the prison population has swelled in the past few years, and abuses by jail guards have been reported at facilities intended for adolescent rehabilitation.

Graphic: Carla Astudillo / International Business Times

“Certain areas where children used to be on the street, they’ve disappeared,” said Beth McLoughlin, a Brazil-based journalist working with the international child-advocacy group Terre des Hommes. “I think [the government’s] main concern is to present an image of harmony to the world, but not to necessarily create that harmony.”

After civil rights advocates condemned the mass arrest of more than 100 young people headed to a Rio beach last summer, Luiz Fernando Pezão, the state’s governor, told media: “How many beach gang assaults have been committed by minors? I am not saying that every minor on the bus was a potential offender, but a lot of them had already been mapped and arrested more than five, eight, 10 or 15 times.”

Twenty-five human rights and community organizations signed a letter in February denouncing the round-ups of street children and questioning government claims that the children were guilty of minor crimes.

“Just thinking they may commit a crime isn’t a reason to put them in a detention center,” McLoughlin said. “This has been a really long-going problem and obviously ahead of these Games it’s becoming even more critical to stop it from happening."

It is in fact a matter of life and death.

Brazil has the second highest rate of child homicide in the world, second only to Nigeria. Unicef, the U.N. children’s agency, reports the number of children killed by violence in Brazil has doubled in the last two decades. As of 2013, the number of youth homicides in the country hit 10,500 per year. And Amnesty International says about 16 percent of Rio’s homicides are carried out by police.

The enforcers appear to operate with impunity. A year ago, Eduardo de Jesus, 10, was sitting by the front door of his home in Rio’s impoverished Complexo do Alemao neighborhood, playing with his cell phone. His mother, Terezinha Maria de Jesus, heard a gunshot and ran outside. Her boy was lying dead on the ground.

“You killed my son, you bastard!” she yelled at a group of military police standing by. One of them answered, she told Amnesty International: “Just as I killed your son, I could easily kill you, because I killed the son of a crook, the son of a lowlife.”

Advocates said such deaths underscored the rampant discrimination against impoverished and dark-skinned Brazilians. Medeiros and others said while wealthy, light-skinned Brazilians can be publicly drunk or rowdy, black and poor youth are regarded with suspicion.

“The number of adolescent homicides is very high, the situation is very, very bad,” said Fabiana Gorenstein, a protection officer for Unicef. “This issue is unfortunately underreported … and the clock is already ticking. We need to stop this.”

But many Brazilians approve of the crackdown. Vinicius Miguel, who works with the rights group Defense for Children International, said the authorities’ harsh tactics ahead of the Olympics reflect a deep-seated animosity toward street children among the broader public.

“There is a widespread appeal for removing them because they are looked at as criminal — a minor criminal — and not just as children with rights,” Miguel said. “Many of these children are in street situations because they are trying to escape a home full of abuses, sexual violence or extreme poverty. And then they face more abuses in the street, sexual exploitation, police violence.”

The official manhandling of Rio’s street kids ahead of the World Cup in 2014 and this summer’s Olympic Games has only added to an extensive list of grievances against the International Olympics Committee and the Brazilian government. Critics of the IOC say the events offer short-term profits for private businesses and industries, but end up hurting many of the host-countries’ most disenfranchised populations.

Already, the ongoing political and economic crises are weakening the safety net. Rousseff’s leftist Workers’ Party, which came to power vowing to combat poverty, is cutting back on social services. The government announced plans last year to hike up taxes and decrease spending by delaying wage increases for civil servants and cutting back on programs that provide sanitation, housing and technical training, intended to save some $5.8 billion a year.

“Image is everything for these events and for politicians and they want to sweep [their problems] under the carpet,” said Christopher Gaffney, a senior research fellow in the Department of Geography at the University of Zurich, who was based for six years in Brazil and studied the official handling of major public events. “We know street children will be rounded up, moved out of tourist areas ... and the police will act with extreme prejudice to maintain an image. These events seem to exacerbate pre-existing conditions.”

The tensions around street children are indeed a pre-existing condition in Rio. The country’s second largest city is often called Cidade Maravilhosa, or the Marvelous City. Its fine white sand beaches are backed by luxurious, high-rise hotels and flanked by looming mountains. Yet the city’s wealth is in sharp contrast to the sprawling shanty towns straddling the distant hilltops, where gang-violence and police abuses run rampant.

Over two decades ago, dozens of kids slept on the steps of Rio’s magnificent Candelária church. The area surrounding the church was something of a makeshift encampment for homeless youth, as church workers offered food and education. The vicinity had become known for its high-levels of crime, including pick-pocketing, prostitution and drugs.

Around midnight on July 23, 1993, two cars came to a screeching halt in front of the church’s steps and a gang of masked men opened fire on the children. Some hid; some ran for cover. Eight boys and girls were killed in what became known as the Candelária massacre.

Some of those responsible for the killings were off-duty military police officers. Only three of the nine suspects were convicted, and the killings sparked a heated debate over youth homelessness and criminality. Human rights advocates argued it was far from an isolated incident — from 1988 to 1991, nearly 6,000 street children were killed in Brazil.

Even a decade earlier, advocates were trying in vain to protect the country’s most vulnerable young. Claudia Cabral’s first job was at a crammed shelter for at-risk youth, some of them just newborns, in downtown Rio de Janeiro. She was studying psychology at the time, and her work with the children, mostly babies and toddlers, was all-consuming: There were more than 80 children under the staff’s care.

Most of them were placed in the shelter by government mandate because they came from poor, favela communities. Their parents would visit on the weekend. But one day, government officials paid an unexpected visit: They ordered all of the children more than 3 years of age to board a bus and drove them away. Neither parents nor shelter staff members were told where the children were being taken.

“The children began to cry as they entered into the bus,” Cabral said. “In my feeling, at that moment, children were not [seen as] people. They were things. They were objects. You put the children here; you put the children there.”

That was 1977. Today, Cabral heads the child-advocacy group Terra Dos Homens, which aims to prevent favela children from falling into homelessness and offers rehabilitation services, including family therapy, for estranged youth. Many of those kids lead lives plagued by drug addiction, violence and sexual exploitation.

It’s a cycle, dating back generations, which Cabral’s organization hopes to break. She sees parallels between the shelter children of the 1970s and the street children and other at-risk youth her organization deals with today.

“When they are in gangs, when they are together and when they are on the streets, just wandering and joking, a lot of people are afraid of them,” Cabral said. “Even for small events, but national events [too], there is always something that they [government officials] do to clean the city and not to show the problem.”

“We have several cases of children being killed, no one knows by who, and considering they have no family, no documents, there are no investigations, no one looks for it.”

Gorenstein, the Unicef researcher, said few cases of street children being killed have appeared in her research, which is based on the latest statistics available from 2013. But such cases are rarely reported, other experts said. And as the Olympics approach, many worry the children who have gone missing could be at risk of physical violence.

“We have several cases of children being killed — no one knows by who — and considering they have no family, no documents, there are no investigations, no one looks for it,” Miguel said.

Human rights advocates, including Andrea Florence of Terre des Hommes, have called on the International Olympic Committee to adopt measures that ensure human rights as a prerequisite to hosting the Olympics.

“We ask they adopt a series of policies,” Florence said. “As a first step, make a commitment and a policy around human rights, and then to take human rights into account in the awarding of the game. And include it in the contracts so it becomes binding on the parties that they report, remedy and assess and have due diligence in place to make sure violations don’t occur before, during or after the events.”

After allegations of abuses linked to both the Beijing and Sochi games, the IOC vowed to require hosts contractually to adopt measures to ensure human rights. Advocates, arguing the promised reforms are overly vague, want a strengthened means of monitoring and evaluating the human rights situations in host-nations. The clause does not come into effect until winter 2022 in any case.

Ahead of the summer Games, Terre des Hommes was one of the organizations that teamed up with Street Child United, a London organization, for an Olympic-style event promoting children’s rights, called the Street Child Games. Teenagers from nine countries, including Mozambique, India, Egypt, Burundi and Pakistan, traveled to Rio for athletic events and a congress on protecting at-risk children.

The events, held over several days last month, finished off with children writing a message to IOC President Thomas Bach, asking him for a “clear public human rights commitment.”

Even advocates don’t see an easy solution. “As a nation, we are blinded — we are so used to the poverty. It’s always here. And we think that’s the only way,” said Medeiros, who volunteers at the Recife safe house. “But these are just children. ... It’s just to find a way to heal a broken heart, to give them a father and mother who love them. They need a family — not a safe house.”

Hosting the Olympics may draw attention to the tragedy of Brazil’s street kids — but also delay any real effort to address the problem.

“The government will do whatever is in its power to clean or to make that area safe just for the Olympic Games,” Medeiros said. “After the Olympic games, okay — that’s it. Everyone can head back.”

“They will mask the truth,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.