Road To Rio: Brazil’s Path To 2016 Summer Olympics Paved With Turmoil

Brazil was booming in 2009 when Rio de Janeiro won its bid to host the 2016 Summer Olympics. Now the country is gripped by political scandal and facing its worst recession since the 1930s.

Pinning business woes on a feckless government can sometimes stretch the bounds of logic, but Robert Mangels can make a pretty persuasive case from where he’s sitting in São Paulo.

The CEO of Mangels Industrial, a metalworking company, Mangels steered his family business into “judicial recuperation” — Brazil’s version of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code’s Chapter 11 — in late 2013. He then squeaked through 2015 by paying the firm’s creditors on time and paying careful attention to the bottom line.

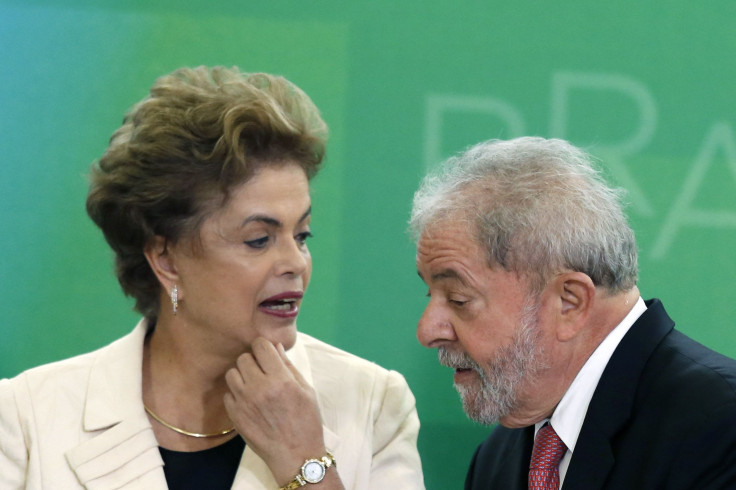

Mangels, whose business activities include making aluminum wheels for Toyota vehicles and refurbishing and making steel propane tanks, watched the Brazilian economy begin to crater in 2014 as prosecutors crept ever closer toward implicating President Dilma Rousseff in an unimaginably wide-ranging corruption scandal that has ensnared dozens of Brazil’s senior politicians. To him, cause and effect appear pretty obvious.

“We cannot blame anybody else for the recession but the government and Dilma,” Mangels said. “We have a recession because there’s a total lack of confidence among investors. Nobody in their right mind is investing in capacity to produce.”

When Brazil was awarded the Rio 2016 Summer Olympic Games in 2009, little appeared to stand in the way of the country achieving the potential that has seemed untapped for decades. It shrugged off the global financial crisis and powered ahead. But the last few years have been brutal. And Brazil has inflicted some Olympic-sized wounds since 2009, on itself.

Brazil has inflicted some Olympic-sized wounds on itself.

Of course, there are reasons for Brazil’s economic woes other than suspicions that Rousseff, a former Marxist guerrilla turned politician, wasn’t up to the task of governing the most populous country in South America. But the downturn on her watch, starting in 2011, would be striking for any nation that didn't erupt in civil strife, experience a major natural disaster or face an enemy invasion.

Rousseff’s troubles look set to deepen Wednesday when Brazil’s Senate will vote on whether to put her on trial for breaking budget rules. If her challengers win a simple majority of the 81 senators, Rousseff will be suspended for up to six months during the trial. Brazil’s Vice President Michel Temer will then assume power, and Rousseff will become the nation’s first leader in more than two decades to be removed from office.

For Brazil’s economy, the near future probably features a period of stagnation, as a government paralyzed by political crisis dodges the tough choices created by strong inflation, rising budget deficits and, at best, a touch of economic growth in 2017 after hitting rock bottom in 2016. That said, there are bright spots, such as Brazil’s highly competitive commodity producers, who should benefit as prices rebound. And the country remains attractive to bargain-hunting foreign investors who see a large, diversified economy, even though Brazilians like Mangels can’t abide Rousseff’s stewardship of it.

If protests constituted an Olympic sport, then Brazilians already would have clinched the gold medal in advance of the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro in August. Demonstrators have turned out in numbers larger than in 1984 — when Brazilians of all stripes united to throw off military rule— to demand Rousseff’s ouster, underscoring how far she and Brazil have fallen.

The year before Rousseff became president in 2010, Brazil won a global race to host the Olympics with visions of a celebration that would confirm the country’s arrival on the global stage. It had glimpsed self-sufficiency in energy as its national oil company, Petrobras, trained its sights on new offshore oil discoveries. And thanks to strong demand for commodities such as iron ore and soybeans, Brazil had ridden Asia’s prosperity to new heights of its own, brushing off the financial crisis ravaging American and European economies.

In 2015, Brazil’s economy shrank by a harrowing 3.8 percent, the result of nothing going right. The country got less for its exports because of sinking commodity prices. Business investment fell. And a government that failed to change during good times had no room for extra spending upon the arrival of bad times.

Stephen Jen, co-founder of SLJ Macro Partners, a London-based research firm, said Brazil — to Mangels’ point — has demonstrated why emerging markets without clean, credible governing institutions eventually get in trouble.

“The reality is that governance matters, even though bad governance could be temporarily hidden when there is a global commodity cycle or a global bubble,” Jen said. “When the tide recedes, the deep-rooted problems are exposed.”

On the plus side of the ledger, the global economy isn’t the only entity exposing Brazil’s problems. So is Brazil’s newly muscular collection of prosecutors, a younger generation that appears determined to root out political graft that was, in its own way, another sport at which Brazilians excelled in Olympic fashion. Even Mangels, who is not prone to kind words about anybody who draws a government paycheck, calls the prosecutors “utterly amazing.”

The Petrobras scandal has wormed its way from the bottom to the top of Brazilian politics. Legally, it’s about a $3 billion pot of bribes and kickbacks to Petrobras contractors, some of which flowed into the pockets of politicians when Rousseff was chairman of its board. More than 100 people have been indicted. Politically, it represents the moment when Brazilians rebelled against a certain way of doing business, one reason why the prosecutors who have pushed Operation Car Wash, the snappy name of the probe, have inspired public trust in a way that judges, lawmakers and administrators have not.

“In Brazil, the district attorneys are now the fourth power,” Mangels said. “I am convinced that they will stop at nothing. There is somebody looking out for Brazilians.”

To many economists’ dismay, there was nobody looking very far ahead for Brazil during the boom that characterized the administrations of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, aka Lula, and Rousseff, at least at the beginning of her tenure. The result is that the macroeconomic problems surrounding government spending are far larger than they needed to be.

“Brazil’s main fiscal problem is that the federal government’s primary expenses have been displaying an upward trend for many years while the primary revenues trend has been declining,” said Enestor Dos Santos, principal economist for Brazil and Latin America at BBVA Research, a unit of Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria.

The budget deficit that was about 3 percent during the boom years more than doubled in 2014 and hit 10.4 percent in 2015. While much of that change reflects lower growth, it is also a function of pension and wage increases that track inflation rigidly, and put the burden of lower spending on the small slice of the budget that can be adjusted.

Brazil can still borrow in its own currency, cutting the risk of a Greece-like boycott by international financial markets. Its floating exchange rate, a policy to which Lula’s government remained firmly attached, helped the country build up ample foreign-exchange reserves. A run on the real is unlikely.

But investors are still demanding rates of between 14 percent and 16 percent for 10-year bonds because inflation, which reached 9 percent in 2015, threatens to erode their value in the event it edges upward. And rising prices limit the central bank’s ability to ease rates to stimulate economic activity, creating a cycle that's hard to break.

In its last major review of Brazil’s policies in early 2015, the International Monetary Fund urged the country to rethink its indexing of pensions and wages to inflation, and also to reform the tax code to eliminate hidden subsidies. The IMF argued that would make room to maintain the social safety net that was a centerpiece of efforts by Rousseff’s Workers’ Party (PT) to ease vast inequality in Brazil.

“There was an easy-to-understand recipe already in place when the PT took power,” said Marcos Casarin, head of Latin America macro research at Oxford Economics. “That’s not there anymore,” he added.

When the PT took power, with Lula as president, Mangels, 64, reacted in horror, as did much of the São Paulo business class. Lula was a longtime communist, a reputation that was not going to disappear overnight. So, Mangels expressed himself sartorially. By nature a genial, beachgoing industrialist, he wore a black suit and black tie for weeks. “That was my protest,” he said.

Lula shocked Mangels, and most of his friends, with his hands-off approach to the economy. Lula appointed an orthodox central bank governor, Henrique de Campos Meirelles, and didn’t meddle in monetary policy. To Mangels’ mind, Lula’s sin came during his final days as president.

“The Lula years were very good,” Mangels said. “But he had the political capital to name the next president, and he chose Dilma.”

The owners of Mangels Industrial — Robert Mangels and his two siblings — will look back on the years from 2014 to 2016 with a mixture of dismay and relief. The abrupt falloff in business forced the company into bankruptcy, but the firm was able to restructure.

“So far, so good,” Mangels said. “It was a very scary moment. But I was quite convinced that it was the only option.”

Mangels Industrial has revenue of about 500 million Brazilian reais ($138 million), down substantially from the boom years. The reorganization cost Mangels the massive steel service center — which formulates and cuts steel to specifications for industrial customers — that it operated in São Paulo. It’s selling a 400,000-square-foot building and the 1 million square feet of land it sits on.

A mainstay business, one that has held up during the recession, has been the refurbishment of propane cylinders, which Mangels carries out at six facilities in Brazil. But the crown jewel of Mangels’ operation is surely its production of aluminum wheels for Toyota vehicles.

Legendarily supportive of its suppliers, the Japanese automaker has stuck with Mangels throughout the recession even as its own sales in Brazil suffered, Mangels said. Toyota has worked with Mangels to improve the quality of the product, which goes into Toyota’s pickups and SUVs made in Argentina, as well as its cars in Brazil.

“Toyota is a reference for us, too,” Mangels said. “If they’re a customer, you must be good.”

Mangels Industrial, and Toyota’s sustained interest in it, highlight the diversity of the Brazilian economy, home to 200 million people in the world’s fifth-largest nation by landmass. For all its weaknesses, the economy still has many small and midsize businesses, and a clutch of global and regional titans that would be the envy of any nation: Vale in mining, Itau Unibanco in banking, Embraer in aircraft. Even scandal-scarred Petrobras still pumps a lot of oil.

Foreign direct investment in Brazil, an indicator of how investors view the country’s longer-term prospects, has dipped in the past few years, but not hugely so, and much of the drop is due to the depreciating Brazilian currency, the real. FDI hit $64 billion in 2013 before declining to $62 billion the following year and $56 billion last year, according to Banco Santander.

The depreciation of the real during the past three years has reduced the cost of investing in Brazil, and the recession has created something of a fire sale in certain areas. Casarin of Oxford Economics pointed out that merger and acquisition activity over the past six months has been dominated by foreign firms.

Simon Whistler, the managing director for political and social risk in Latin America at the consultancy Control Risks, said his clients find prices attractive. “We are talking private-equity and foreign investors who have an interest in Brazil because everything is so cheap right now,” Whistler said.

The Carlyle Group, the Washington-based private-equity firm, bought an 8 percent stake in a Brazilian hospital operator, Rede D’Or, for $603 million last year. In late February, it completed the acquisition of a distance-learning company in a partnership with a Brazilian asset manager, for $285 million, and is looking through the political turmoil to the country’s longer-term future.

“We seek out companies that have the capacity to offer services that remain essential to Brazilians,” Fernando Borges, co-head of Carlyle South America Buyout group, said in a statement. “This is Carlyle’s first investment in Brazil’s education industry, whose fundamentals remain promising.”

Likewise, the sheer scale of Brazil’s commodity businesses means they are bound to profit from a global shakeout among less efficient producers.

This month, Roger Agnelli, who was CEO of the iron miner Vale from 2001 to 2011, died in a plane crash that also killed his wife and two children. But Agnelli’s work in turning the company into not only a Brazilian standout but also a global titan in its industry, will outlive him, another indicator of the country’s resilience.

“We cannot blame anybody else for the recession but the government and Dilma.”

Vale consolidated over 80 percent of Brazil’s iron ore production, and it owns rich, easy-to-mine deposits near the country’s northern coast. Given that its competitors’ less-efficient mines elsewhere in Brazil, Australia, Canada and the U.S. all shut down under the pressure of low prices, Vale stands to pick up market share.

“They can produce ore at so much lower costs,” said Cliff Smee, senior analyst for mining at Timetric, a London-based consultancy. The less-efficient producers “rode the boom of the Chinese demand story for the last 10 years.”

The trick for titans such as Vale and midsize businesses such as Mangels Industrial will be to steer through the political riptides.

Paul Domjan, managing director at Roubini Global Economics, an economic research firm, said the mix of political and economic challenges remain to be tackled. Dogged prosecutors are good, but they’ll uncover more rot in the Brazilian system before they are done.

“The business environment has been weakened by poor economic performance, and this could become an even bigger issue for firms operating in Brazil,” Domjan wrote in a recent report. “Even the potential upside from rooting out corruption is bringing significant collateral damage as cases work their way through the legal system.”

Mangels, out of bankruptcy and paying down debt, called his judicial filing a “scary moment” for his family business. Brazil, as a whole, may have a few more moments like that in the months ahead.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.