Rugby League: A Sport At The Beating Heart Of Communities

Rugby league does not boast a global reach or the deep pockets of other sports as it attempts to navigate its way through the financially perilous coronavirus crisis.

But clubs in the heartland of the English game have an enduring and profound connection with the northern, working-class communities in which they are based.

The sport was handed a lifeline this month when the government announced the Rugby Football League would receive a ?16 million ($20 million) cash injection.

RFL chief executive Ralph Rimmer told AFP the loan was crucial for clubs, which he said operated like another arm of social services, running programmes in areas such as autism, dementia and mental health.

He described the clubs as "the heartbeats of their communities".

That role was underlined by last year's Rugby League Dividend Report, commissioned by the RFL, which highlighted the positive social and economic impact of the sport in disadvantaged areas.

"It was about the level of impact clubs and their works had on communities and, cutting through to the quick, they said that for every pound you spend you get four pounds back," said Rimmer.

Many rugby league clubs have well-established charitable programmes and have adapted these to help the vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic.

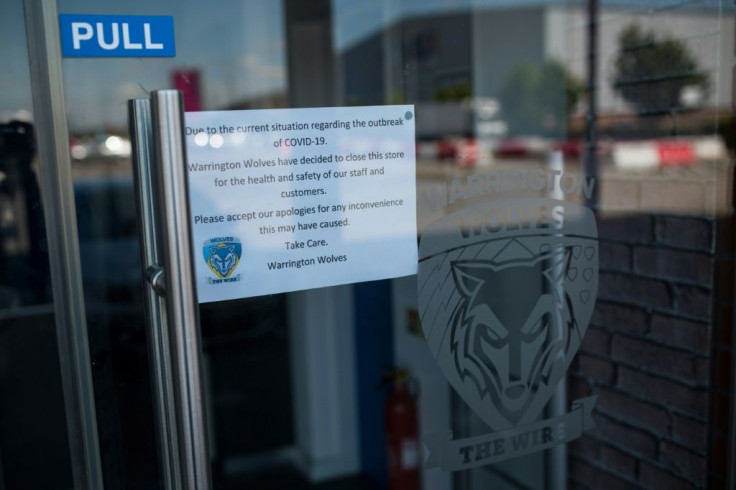

Hull have delivered food parcels to elderly people who are self-isolating, while players from Widnes and Warrington have been calling supporters to check on their wellbeing.

Rimmer highlighted food deliveries being made by former Great Britain captain Paul Sculthorpe and the work of Bradford Bulls Women's player Amy Hardcastle, who has a health service role.

Rugby league historian Tony Collins says rugby league clubs are just as important to their local communities as when the sport began in 1895, after a split from rugby union.

"The club is the only thing in some of these towns that gives them a sense of identity," said Collins, who added that the sport had faced "existential problems before", but nothing on the scale of the coronavirus pandemic.

"Look at most of the towns where there are clubs and through no fault of their own there is very little else that gives those towns any sense of civic identity on a national scale.

"However, ask anybody in the street what they think of when you mention Wigan and they will say rugby league, same with St Helens and Widnes."

Collins said rugby league was "as much a social movement as a sporting movement". Most players have been amateurs, living and working alongside those who would watch them each week.

He uses the example of the role clubs played during the bitter miners' strike in Britain in the mid-1980s.

"In 1984-85 rugby league clubhouses the miners' families would pick up food parcels and they would hold community meetings," said Collins.

"Many pit villages in Yorkshire and Lancashire, the only thing these villages would have would be a pit, a pub and a rugby league club."

Collins fears for the future of lower-tier clubs even if there is a resumption of the season behind closed doors because of the lack of TV money and the absence of fans but he said there were rays of hope.

He is confident that the needs of the rugby league heartlands are on the government's agenda after many voters switched sides to vote for Boris Johnson's Conservatives in December's general election.

"There is an element of payback," he said. "When the election was announced one Conservative think-tank highlighted 'Workington man', a voter from a former industrial town and a strong rugby league supporter.

"So you can factor that in as well."

And Collins says that when clubs are under threat of closure fans traditionally rally round.

"It goes back to the Depression," he said. "Clubs had their backs against the wall and people went out into the community and raised money.

"The fact it is strong in the community, it is unlikely even when under tremendous financial pressure that it will die."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.