For Russian Prisoners, Letters Provide Rare 'Moment Of Joy'

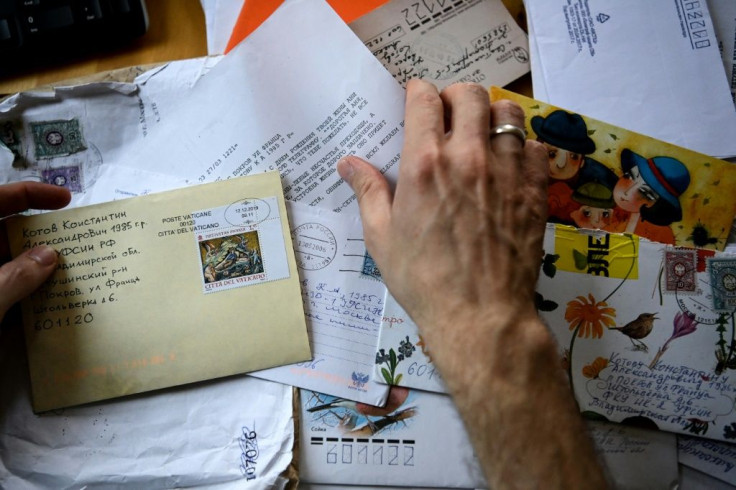

In a cottage outside Moscow, Konstantin Kotov goes through a handful of the hundreds of letters he received when he spent more than a year behind bars for violating Russian protest rules.

The opposition activist served his sentence in Penal Colony No. 2 in Pokrov -- a notorious prison 100 kilometres (60 miles) outside Moscow where opposition leader Alexei Navalny is currently held.

Kotov, who was released last December, says he endured a "wall of silence" after prison authorities banned other inmates from speaking to him.

Now a free man, the 36-year-old says the letters -- most of them hand-written -- stopped him from "breaking down".

Phone calls and visits are limited in the Russian prison system and contact with the outside world is particularly restricted for political prisoners, who are often subjected to greater isolation than ordinary inmates.

With letters being the only effective means to communicate, activists have taken to social media to encourage Russians to write to those they consider to be political prisoners.

Kotov recalls having an hour a day under strict surveillance to read the letters.

"It was always a moment of joy," he says. "It allowed me to preserve the freedom inside me that they tried to take away."

Kotov, who was jailed for participating in multiple protests during anti-Kremlin demonstrations in the summer of 2019, says he would often receive letters several months late, as they had to go through prison censors first.

Critical references to President Vladimir Putin were blotted out from the letters, he says.

Tired of reading and censoring his flow of letters, prison authorities offered Kotov better conditions if he stopped replying to them. Kotov refused.

Navalny -- who has compared the Pokrov prison to a concentration camp -- also complained about the censors in a satirical message published by his team on Instagram earlier this year.

"I'm like Harry Potter in the first book, remember the letters from Hogwarts?" he said, referring to the fantasy series' hero having his letters taken away from him.

"It's the same for me but without the owls and wizards."

In the post, he called on his supporters to write to other political prisoners in Russia so they "do not feel alone".

AFP asked Russia's Federal Penitentiary Service for comment on the censoring of prisoners' letters but did not receive a reply.

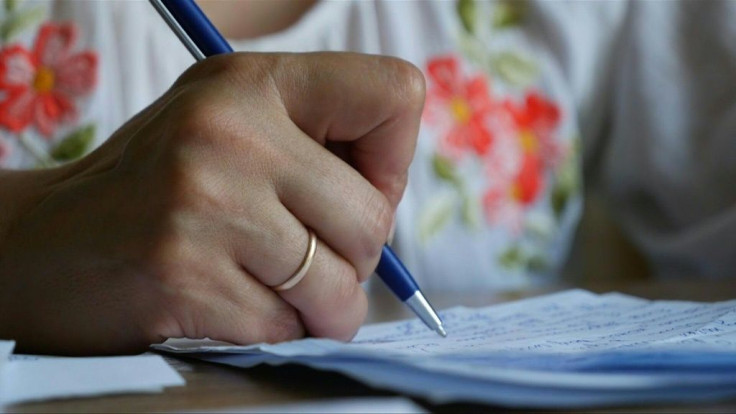

Irina Vladimirova, a 50-year-old former university lecturer, is one of many volunteers writing to the country's growing list of political prisoners.

She gets their addresses from social media, where activists share a database of who they consider to be political prisoners and where they are serving their sentences.

Writing in her small Moscow kitchen, Vladimirova estimates she wrote around 600 letters to prisoners in six years, calling it her personal act of protest.

When AFP visited her apartment, she was writing to five inmates recognised as political prisoners by local rights group Memorial, including a retired Ukrainian captain, a historian and a student arrested over protests.

"I hope a star shines bright for you," she wrote in one of the letters.

She puts extra stamps and paper inside each envelope so the prisoners have a chance to write back.

Yuri Dmitriyev is one of those who does.

A historian who uncovers Stalinist crimes, Dmitriyev was sentenced to 13 years in prison on controversial paedophilia charges that rights groups deem political.

"He tells me not to worry," Vladimirova says.

Olga Romanova, who runs the Rus Sidyashchaya (Russia Behind Bars) group providing legal help for prisoners, says the letters can help protect from physical violence.

"The more letters a political prisoner receives, the more he is protected," she says, adding that guards are afraid to "touch" inmates who receive attention from the outside world.

"Letters are a very important (support) instrument," the 55-year-old says.

"I do what I can," she says. "I write letters."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.