Russia's Ruble Stages Rebound Despite Western Sanctions

After a historic collapse in the wake of Russia's military offensive in Ukraine, the ruble has staged a spectacular bounceback, supported by strict capital controls and energy exports.

But analysts say that success is in many ways artificial and does not bode well for the health of the Russian economy.

The February 24 military operation triggered unprecedented Western sanctions on Moscow, sending the ruble into free-fall and accelerating already high inflation.

Four days after President Vladimir Putin sent troops into the pro-Western country, the central bank more than doubled its key interest rate to 20 percent to prop up the financial system.

In a surprise move on Friday, the central bank lowered the rate to 17 percent, saying risks to financial stability had "ceased to increase" for now.

"It's clear that the Central Bank of Russia assesses that Russia's economy is now emerging from the most acute phase of its crisis and that such restrictive monetary conditions are no longer warranted," said Liam Peach, emerging Europe economist at Capital Economics.

The ruble's return to levels last seen before the start of Moscow's military campaign is a sign that the economy may be adjusting to the sanctions, economists say.

Sofya Donets, chief economist at Renaissance Capital, said the ruble recovery has been aided by an unprecedented trade surplus amid high energy prices.

"There has been a decline in imports, partly because of sanctions, partly because of uncertainty and logistical disruptions," she told AFP.

"But exports are solid, and with commodity prices high we expect a historically high account surplus of $20-25 billion in March."

Oil and gas, Russia's main exports, keep flowing abroad, filling Russia's coffers.

The United States has banned Russian oil imports and the EU adopted a ban on Russian steel imports but those penalties have largely spared key Russian exports.

"It only affects five percent of Russian exports, so it's not that much," said Donets.

Robust exports have been supplemented by harsh capital controls introduced by the central bank.

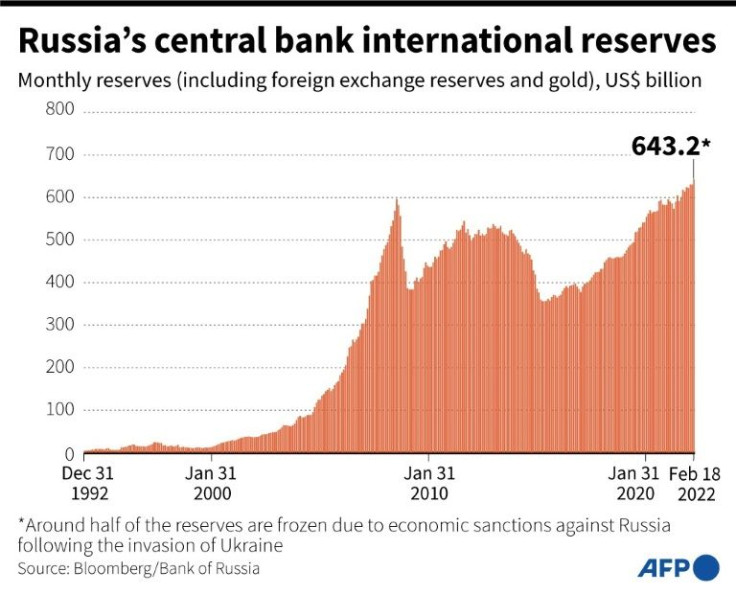

The West froze some $300 billion of Russia's foreign currency reserves abroad, a move that Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has described as "theft".

To counter the sanctions, exporting companies were forced to sell 80 percent of their export earnings to buy rubles.

Russians have also been barred from withdrawing more than $10,000 in foreign currency or taking more than that amount out of the country, and foreign investors have been banned from selling Russian assets.

Late Friday the central bank relaxed some curbs, saying that from April 18 it was scrapping the ban on buying dollars and euros introduced in early March.

The rapid ruble recovery does not equal a strong economy, however, analysts said.

"Russian equities and the ruble currently remain decoupled from global macro factors and news flow due to capital controls," Alfa Bank said in a note.

The lender estimates that the ruble will be trading at around 80-85 to the dollar in the near future.

Economists believe that the worst economic impact of the sanctions is still to come and expect Russia, which has relied heavily on imports of manufacturing equipment and consumer goods, to plunge into a deep recession.

Russia's inflation rate reached 16.7 percent year-on-year in March, the state statistics agency said on Friday, a level not seen since 2015, while food prices have risen even more steeply.

Capital Economics pointed out that the 7.6 percent month on month rise in consumer prices in Russia in March was "the highest monthly increase since the 1990s."

Renaissance Capital analysts predict that annual inflation will peak at 24 percent this summer.

Donets said that "the market is destroyed in a sense."

"We have a closed financial system now," she added.

"Where would the ruble rate be if there were no capital controls? It's very hard to say, there has been no precedent."

Timothy Ash, an emerging markets strategist at BlueBay Asset Management, was more blunt, saying the Bank of Russia was "heavily managing/manipulating this."

"It's not a liquid market," he told AFP in emailed comments.

"This is a PR campaign by the Central Bank of Russia as a tool of the Kremlin."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.