Scientists Discover Ancient Enzyme That Functions Without 'Decorations' In Humans

Enzymes — proteins that catalyze complex biochemical reactions — have been around for hundreds of millions of years. Some studies suggest that bacteria living over 3 billion years ago also possessed sophisticated enzymes — although they were less specialized than their present-day counterparts.

Modern enzymes are believed to have descended from these ancient ancestors, evolving, over billions of years, to perform a raft of functions in complex life forms, including in humans.

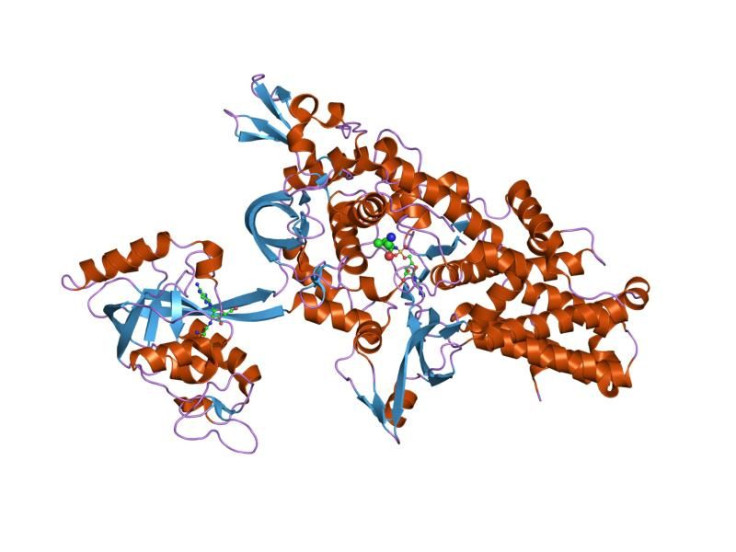

One such family of enzymes is the aminoacyl tRNA synthetase, which is responsible for catalyzing the reaction that "charges" transfer-RNA with an amino acid.

"Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases are associated with — and we believe needed for — the building of organismal complexity, such as making tissues and organs in humans," Paul Schimmel from the Scripps Research Institute in California explained in a statement released Friday.

This ancient enzyme serves its new functions with the help of additions — or "decorations" — that are lacking in bacteria. However, Schimmel and his colleagues have now discovered an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase called AlaRS that lacks any new decorations and can somehow still carry out its new role in humans without overhauling its basic architecture.

"AlaRS presented an exception to what we thought was a 'rule,'" Schimmel said.

So how does this ancient enzyme manage to perform the functions that lie beyond its original scope? By reshaping part of a structure known C-Ala in a way the researchers compared to reshaping an airplane’s wing to serve as its tail.

Scientists believe further studies investigating the function of the reshaped C-Ala may shed light on diseases linked to mutations in aminoacyl tRNA synthetases.

"This work illustrates nature’s efficiency — how it can take one thing and convert it to another, with a tweak here and a tweak there," Schimmel said. "Nature has provided ways for reshaping objects, like C-Ala, and when that happens, new functions occur."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.