Scottish Independence Vote Reignites Separatists Across Europe

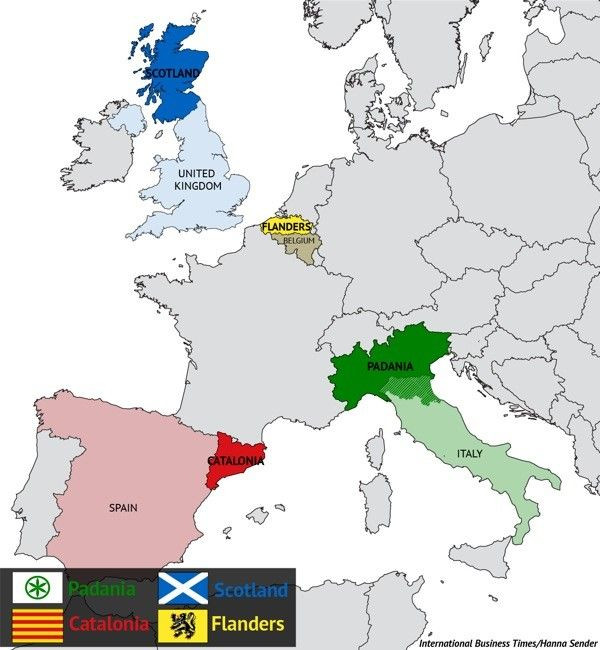

With just two days to go before Scotland votes on its independence, separatist movements across Europe have become energized by the real possibility that the United Kingdom could be about to split. Europe is awash with a number of pro-independence entities, but those in Spain, Belgium and Italy have seized the moment to reignite their own agendas.

“If Scotland wins it will be a breath of fresh air for Europe,” said Matteo Salvini, the leader of Italy’s Northern League. “There will be [in Scotland’s footsteps] Veneto, Lombardy and Salento [the southernmost tip of the heel of Italy]. The fact alone that Scotland is voting is historical unto itself. It’s an important step towards democracy. We never stopped the independence fight against the European regimes and the regime in Rome,” he said on Saturday.

His words could be taken as an avatar for many of Europe's separatists, who plan to use the Scottish referendum -- regardless of the result -- as a springboard to achieve their goal of a small, independent republic. The crisis that has wrecked European economies since 2008, with rising unemployment and falling standards of living, has bolstered many of the continent's independence movements, giving credibility to the argument that central governments and a distant, bureaucratic European Union in Brussels are an obstacle imposed on areas that would otherwise do well economically.

In that context, we'll examine the three independence movements that have been the most active in pursuing gains from the Scottish referendum.

Italy: The Rich North Wants Out

The separatist Northern League, which has often said it wants the North of Italy to break off from the rest of the nation, has lost some of the clout it had in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when it was a national governing force allied with Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and managed to push through a federalist reform that devolved some powers, especially tax revenues, to Italy's local governments.

Its fortunes have floundered since its popularity peaked in 1996, when it captured 10 percent of the Italian vote and was the largest party in Northern Italy. Hit hard by an embezzlement scandal in 2012 that brought down its founder, Umberto Bossi, the League is now in the opposition, but is still a force to be reckoned with nationwide, garnering 1.7 million votes in this year's European Parliament election.

In practice it has generally acted as a federalist party, pursuing more powers for Italy's 20 regional governments and thousands of city administrations, and lately taking on an especially tough stance against immigration and the euro. Some of its members have been known for racist statements: A promiment League senator compared Italy's first black government minister to an orangutan, and one of its deputies at the European Parliament reacted to Barack Obama's 2012 victory by lauding the Ku Klux Klan and Confederate soldiers.

The League has in fact never held a secession referendum. Yet its formal name remains "Northern League for the Independence of Padania," and the threat of secession is often part of the League's political rhetoric.

The economic reasons behind language like Salvini's are obvious. Unemployment in the South of Italy reaches 15 percent, while it's just around 5 percent in the industrial North, which also transfers wealth via taxes to the South, a net recipient of public funding. GDP per capita in Lombardy, the North's richest region, is 32,000 euros, above the national average, but only half that in most Southern regions.

There's a major problem, though, with any push for independence the League may choose to support: No one really knows what Padania is. The term is, somewhat ironically, derived from the Latin Padus, the name the Romans gave to the Po River that bisects Northern Italy; the League, whose trademark slogan lambasts "Rome The Thief" for taking Northern taxes, never had any qualms about using a name coined by Roman colonizers. It also never really defined which regions would be part of an independent Padania.

Belgium: Two Languages, Feeble Governments

Another European nation rattled by a nationalist movement is Belgium, where the Dutch-speaking Flanders region has aspirations to break away from their considerably poorer French-speaking countrymen in Wallonia.

While the idea of partition is relatively new, it has come to the fore after years of political uncertainty in the country, which -- despite being the seat of the European parliament and of the European Commission, the executive arm of the EU -- has seen governments fall regularly as multiparty coalitions continuously disagree. Between 2008 and 2011, for example, the country had four different prime ministers, with one serving twice after a gap of just one year. In addition, the country undertook what may have been the longest formation of government in history, taking 589 days of negotiations before finally forming a government in December 2011. (The previous record was held by Cambodia.)

To underline the internal strife, ex-Prime Minister Yves Leterme said in 2010, amid the most volatile period in Belgian politics, that the country was an “accident of history” and that it had amounted to nothing more than “the king, the national football team and certain brands of beer.”

This uncertainty has left Wallonia particularly concerned by the possible partition of Belgium. So much so that its main political party has suggested the region might join France if Belgium splits.

But the Flemish appetite to separate, while steeped in cultural differences -- Flanders is culturally Dutch, Wallonia sees itself as close to France -- is largely to settle political uncertainty. There hasn't been a serious consensus to split since around 2007, another time when the country struggled to form a working government. Even then, only around 49 percent favored a split. Today, Flemish separatist party Vlaams Belang has just three seats out of 150 in the federal parliament, six out of 124 in the Flemish parliament, and has effectively been isolated from power. The more moderate New Flemish Alliance has 20 percent of the 150 seats in parliament, but a fragmented representation means the numbers for a coalition supporting independence for Flanders just are not there.

Spain: A Popular Movement, A Reluctant Madrid

Perhaps the biggest and most popular separatist movement can be found in Northern Spain, where the Catalans have been attempting to gain independence for decades. There is a clear support for separation with more than 55 percent of Catalans in favor, but those aspirations have, to some extent, been undermined by the terrorist group that has long supported independence for the nearby Basque region, ETA.

Madrid, the decision maker, has no stomach to further fuel the aspirations of the Basque people (who reject ETA tactics by a large majority, to be sure) by allowing Catalonia to go it alone. Madrid is so opposed to independence by any of Spain's autonomous regional entities that it has actively campaigned through the European Union to stop Scotland ever being able to join the EU if it were to become independent, even though it has been part of the EU through the U.K. for 40 years.

The Madrid government views separation as anathema, and has said that it has absolutely no agenda to hold any kind of referendum that would see the country potentially split.

The Catalan argument is far simpler and more clear cut than either Scotland’s or Belgium’s: The people are deeply passionate about Catalonia being an independent state. Over the last 17 years, Catalans have consistently voted for independence in mock referendums. On Nov. 9 there will be another referendum, asking two questions: “Do you want Catalonia to become a state?" and "In case of an affirmative response, do you want this state to be independent?" The only problem is, the vote is not politically binding, and the Madrid government has vowed to stop it from happening in the first place.

The Catalans contend that they would financially prosper as an independent state. In nominal gross domestic product terms, the Catalan economy would, in fact, be bigger than Scotland's, according to government statistics.

Support for independence is around 50 percent of the electorate, according to a 2012 poll. On Sept. 11, a demonstration for independence in Barcelona, the Catalan capital, attracted hundreds of thousands of people.

That mass demonstration was peaceful, just as the Flemish and Northern Italian demands have not been accompanied by violence.

And should Scotland gain its independence, it will have done so in a way that Europe has rarely seen: without war. Since the beginning of the 19th century the only splits agreed upon peacefully, not counting the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, have been Norway's from Sweden in 1905 and the separation of Czechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1993 after the 1989 Velvet Revolution. The other countries that have gained independence in Europe have done so through war.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.