Senate Set To Approve The Trans-Pacific Partnership, But What Exactly Is It?

These days it is called the TPP-11 or, more formally, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans Pacific Partnership.

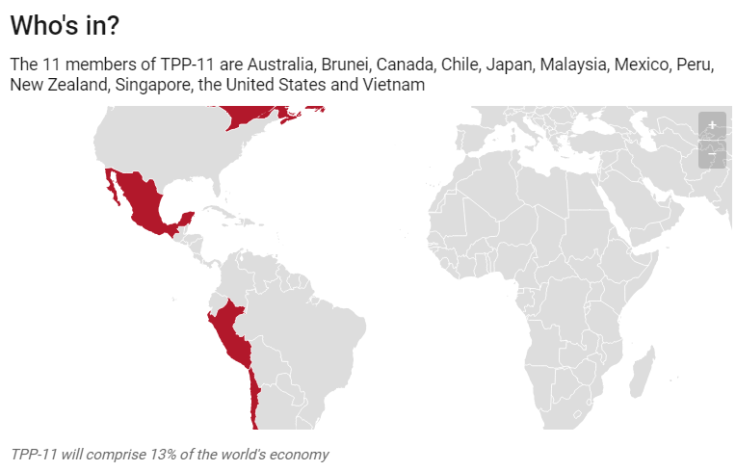

It is what was left of the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership after President Donald Trump pulled out the US, after a decade of negotiation, in 2017.

Still in it are Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Japan, Brunei, Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam. It’ll cover 13% of the world’s economy rather than 30%.

What’s in it for us?

It is hard to know exactly what it will do for us, because the Australian government hasn’t commissioned independent modelling, either of the TPP-11 before the Senate or the original TPP-12.

A report commissioned by business organisations, including the Minerals Council, the Business Council, the Food and Grocery Council, the Australian Industry Group and the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, finds the gains for Australia are negligible, eventually amounting to 0.4% of national income (instead of 0.5% under the TPP-12).

The report says:

The reason is simple: Australia already benefits from extensive past liberalisation, especially with Asia-Pacific partners.

But it says bigger gains would come from expanding TPP-11 to many more members, all using “common rules” and the same “predictable regulatory environment”.

Gradual deregulation

Setting up that predictable environment takes an unprecedented 30 chapters, covering topics including temporary workers, trade in services, financial services, telecommunications, electronic commerce, competition policy, state-owned enterprises and regulatory coherence.

Most treat regulation as something to be frozen and reduced over time, and never increased.

It’s a regime that suits global businesses, but will make it harder for future governments to re-regulate should they decide they need to.

Our experience of the global financial crisis, the banking royal commission, escalating climate change and the exploitation of vulnerable temporary workers tells us that from time to time governments do need to be able to re-regulate in the public interest.

International ISDS tribunals

And some decisions will be beyond our control. In addition to the normal state-to-state dispute processes in all trade agreements, the TPP-11 contains so-called Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) provisions that allow private corporations to bypass national courts and seek compensation from extraterritorial tribunals if they believe a change in the law or policy has harmed their investments.

Only tobacco cases are clearly excluded.

ISDS clauses will benefit some Australian-based firms. They will be able to take action against foreign governments that pass laws that threaten their investments, although until now there have been only four cases. John Howard did not include ISDS in the 2004 Australia-US FTA, following strong public reaction against it.

Known ISDS cases have increased from less than 10 in 1994 to 850 in 2017, and many are against health, environment, indigenous rights and other public interest regulations.

If, after the TPP-11 is in force, a future government wants to introduce new regulations requiring mining or energy companies to reduce their carbon emissions, it is not beyond the bounds of possibility that companies headquartered in TPP-11 members might launch cases to object.

Legal firms specialising in ISDS are already canvassing those options.

Even where governments win such cases, it takes years and tens of millions of dollars in legal and arbitration fees to defend them. It took an FOI decision to discover that the Australian government spent $39 million in legal costs to defend its tobacco plain packaging laws in the Philip Morris case. The percentage of those costs recovered by the government is still not known.

A limited role for parliament

The text of trade agreements such as TPP-11 remains secret until the moment they are signed. After that it’s then tabled in parliament and reviewed by a parliamentary committee.

But the parliament can’t change the text. It can only approve or reject the legislation before it.

In another oddity, that legislation doesn’t cover the whole agreement, merely those parts of it that are necessary to do things such as cut tariffs.

The parliament won’t be asked to vote on Australia’s decision to subject itself to ISDS, or on many of the other measures in the agreement that purport to restrict the government’s ability to impose future regulations.

Could Labor approve it, then change it?

In the midst of internal opposition to TPP-11, the Labor opposition has decided to endorse it and then try to negotiate changes if it wins government.

In government it has promised to release the text of future agreements before they are signed, and to subject them to independent analysis.

And it says it will legislate to outlaw ISDS and temporary labour provisions in future agreements.

But renegotiation won’t be easy. Labour will have to try to negotiate side letters with each of the other TPP governments. If the TPP-11 gets through the Senate, Labor is likely to be stuck with it.

Pat Ranald is a research associate at the University of Sydney.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the original article here.