Shrapnel: The Terrible Fragments Of War

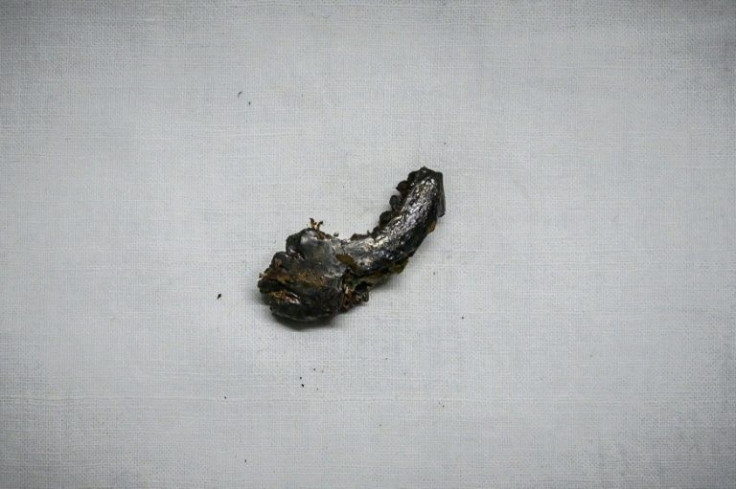

They differ in size and colour and some still have skin attached: the shrapnel extracted from the wounded at a military hospital in southern Ukraine are the cold reality of the country's war.

In this closely guarded building in the city of Zaporizhzhia, the windows are covered in tarpaulin to avoid drawing Russian fire and to protect patients if the windows shatter from a blast.

There is therefore near total darkness as surgeons come out of an operating theatre with their metallic haul -- two jam jars filled with the shrapnel taken out of soldiers and civilians undergoing treatment at the facility.

Some fragments are bottle green, others grey or brown.

"That's from a mine," said one of the doctors, Yury, pointing to a shard four or five centimetres long.

Every scrap of metal has a story.

Pointing to a particularly sharp shard, Yury said: "We took that one out of a leg. The soldier was in a stable condition and the operation was a success".

On his phone, he showed an X-ray of the wound as it was before the operation. The piece of metal stands out whiter than the muscle in which it was embedded.

Other X-rays show a bullet lodged in someone's jaw or a piece of shrapnel lodged in a pelvis.

"Our men are very strong. A large majority of the ones that we treat here, even those who are seriously injured, want to return to the frontline with their friends to support them," Yury said.

An orthopaedic surgeon, Farad Ali-Shakh, said that none of the wounded had died at the hospital and there had only been two limb amputations.

"Their injuries were putting their life in danger," he said.

He too showed a picture on his phone of a blown-off foot, attached to the rest of the body by some skin.

"We managed to restore the vessels and then fix the extremities," said the surgeon.

Ali-Shakh said he is working 20 hours a day.

"We basically live here," he said. "Sometimes I get home at 2 or 3 in the morning and then I come back".

Since the start of Russia's invasion on February 24, the hospital has treated more than 1,000 wounded, including both military and civilians, according to hospital director Viktor Pysanko.

The conflict that began in 2014 with Russia-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine had been "low intensity" and wounds were relatively simple.

The injuries are now much more complex and reflect the range of ordnance being used, Pysanko said, angrily branding Russian soldiers "animals".

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.