With Streets Silent, Latin American Activists Use Walls To Speak Out

Coronavirus lockdowns may have largely silenced various social movements but a new form of protest is spreading on the walls of buildings in Colombia and elsewhere in Latin America.

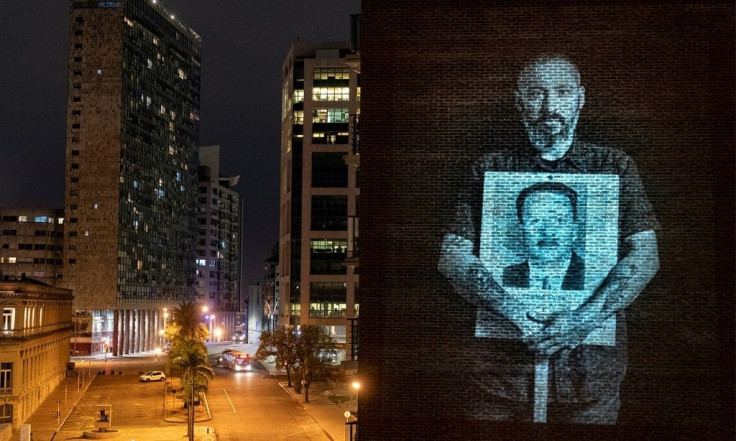

Social activists are beginning to find their voice again, projecting words and punchy images onto the walls of towering buildings.

These include everything from "Bolsonaro Out" slogans against the Brazilian president in Sao Paulo, to "No one is above the law" hailing the arrest this month of former Colombian president Alvaro Uribe.

"We decided that it was a nice idea to keep that protest spirit alive and not let the coronavirus overshadow things that continue to happen and that need to remain in the national conversation," said Laura Mora, a 39-year-old filmmaker using this new form of expression in Medellin, Colombia.

"And if we can no longer go out on the streets the walls serve as a printing press."

On an April evening, months into Colombia's lockdown, Mora and her 42-year-old musician friend Sergio Parsons climbed onto the roof terrace of their apartment building to break the monotony of confinement with an open-air cinema screening for friends.

A neighbor set up a projector. "But there was a crazy gust of wind," which blew their screen away.

"But we realized we had this wall," she said, pointing to the building opposite, and the messenger had her medium.

"We're inspired by the spirit of the events of late 2019," said the director. "A lot of people have written to me. One of them said, 'I've got a projector, let's join forces.'"

The following Sunday, the walls of several Medellin neighborhoods lit up in the night -- the work of street artists, illustrators, publishers, musicians.

Until then, they had never met. Now, with half a dozen projectors, they are making walls talk in Colombia's second-largest city.

The messages are disparate, ranging from the sign-of-the-times standard "Everything's strange" to slogans like "Public health for all" to calls for the legalization of abortion or denouncements of Colombia's "narco-democracy."

"We think it's very interesting to keep shouting what there is to say," adds Juan David Mesa, 29, a film producer who projects images and slogans onto the walls of Medellin's cathedral from the Plaza Bolivar below.

The activists are also sharing their messages on social media.

"By putting it here our neighbors can see it but the good thing about social media is that it makes it permanent," said Tatiana Rios, a visual designer.

As countries have withdrawn into themselves during the pandemic, this new form of protest has jumped borders, reaching cities across Latin America via social networks.

"We're connected with a projection initiative in Sao Paulo in Brazil, another in Chile, a girl in Uruguay. There are others in Mexico who have a mobile projector and move around," said Mora.

The movement is still in its infancy in Colombia, having just reached the capital Bogota where a political scientist projected images from her balcony but was asked to turn it off by a neighbor.

So far, the silent protests have largely been well received by the public.

"People notice the reflections, turn around, stop, read, take photos and look for the source of the projection. Sometimes they laugh and wave," said Maritza Sanchez, 37, a journalist with an alternative radio station.

The biggest impact has come via social media. Mora's Instagram account @lanuevabandadelaterraza has attracted more than 8,000 subscribers in three months.

That evening, a projection showed a portrait of the influential right-wing leader with his face decomposing, alongside a slogan about him being put behind bars.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.