Syrian Refugees Heading To Europe Are Big Business For Lebanon's Travel Agents

TRIPOLI, Lebanon -- For the first time in her three short years, Hanan didn’t wake up in a country at war. The night before, on Saturday evening, Hanan’s parents bundled her up to execute their escape from the ruins of Aleppo in northwestern Syria. The little girl took only what she considered essentials: white, gemstone-encrusted shoes, earphones and purple polka-dotted sunglasses. By the morning, she was listening to music with her parents, sitting at a pink plastic table at a makeshift cafe outside the port in Lebanon’s second city, Tripoli.

Many Syrians have fled war-torn cities before them. But unlike the 1.7 million Syrians who have settled in for a long stay in Lebanon, Hanan’s family is just stopping in Tripoli for one day before joining the mass exodus of refugees taking ferry boats to Turkey, hoping to reach northern Europe.

Since January, more than 640,000 refugees and migrants have arrived in Europe, more than half of whom are Syrians “moving from host countries in the region or from Syria transiting through host countries in the region,” with a “spike” in refugees coming from Syria directly, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Roughly 2,500 passengers depart from Tripoli port every day, port director Ahmad Tamer told China's Xinhua News. In August alone, 28,000 passengers took the ferry to Turkey from Tripoli, a massive jump from 2014, when the annual number of passengers making the same journey was 54,000. The majority of passengers come straight from Syria, but others are Syrian refugees who have been living in Lebanon since the war began.

International Business Times visited a Lebanese army unit in Tripoli to determine the exact number coming directly from Syria, but the officer on duty said he was not able to share that information. However, Lebanese officials told the Washington Post that the number of Syrians taking ferries to Turkey more than doubled between July and August of this year, with each ship transporting between 300 and 1000 people.

The majority of Syrians traveling through Lebanon to catch the ferry to Turkey are doing so legally, planning their route based on the advice of family and friends who went before them, and paying companies who handle the entire process. Even formerly affluent civilians in areas considered relatively safe are now fleeing, nearly penniless, as foreign powers become increasingly embroiled in the conflict, after more than four years of civil war.

“There’s no one left in Aleppo between the ages of 18 and 35,” said Morhaf, Hanan’s father. “Everyone is in Turkey, including my brothers and my sisters. My father is the only one left.”

Hanan and her parents made their way from a regime-controlled area of Aleppo to the Syrian capital of Damascus before taking a taxi across the border to Tripoli. Privately owned Syrian and Lebanese taxi companies make dozens of these trips every day, charging some $100 a person. They family aimed to meet Morhaf’s family in Turkey before joining Hanan’s maternal grandparents in Germany. Aside from Hanan’s favorite toys, the family left with only their clothing packed into four suitcases.

The journey from Syria to Lebanon is legal, but safe passage is a challenge. Lebanon has taken the highest number of Syrian refugees per capita, and since the start of the Syrian conflict, roughly 1.2 million Syrians have registered with the UNHCR, the primary international body in charge of Lebanon’s refugees. The actual number of refugees living in Lebanon is believed to be much higher since the Lebanese government banned the UNHCR from registering anyone new as of May, forcing some Syrians traveling to Lebanon to do so illegally, or to only stay for a few days before leaving for Turkey.

Under the new law, Syrian refugees entering Lebanon have to prove they’re staying in a hotel, or have a Lebanese citizen willing to sign off as a sponsor, agreeing to be financially responsible for them. This has made it increasingly difficult for refugees to enter or leave Lebanon without proper documentation, which has resulted in what UNHCR described as a “spike” in Syrian refugees trying to get to Europe from Syria directly, like Hanan and her family.

“Even a cat is not allowed to leave without his passport,” joked Abdullah, a skinny 23-year-old Lebanese mechanic whose shop is next door to Tripoli port.

Enterprising companies are taking advantage of the large number of refugees transiting through Tripoli by offering complete travel packages from Syria to Turkey. Many refugees IBT spoke to use Altair Shipping Agency, a privately owned Lebanese company that operates both cargo and passenger vessels. The company owns and operates the tri-weekly ferries that leave from Tripoli and arrive, 12 hours later, in Mersin, a port on the Mediterranean where thousands of Syrian refugees have landed since the war began.

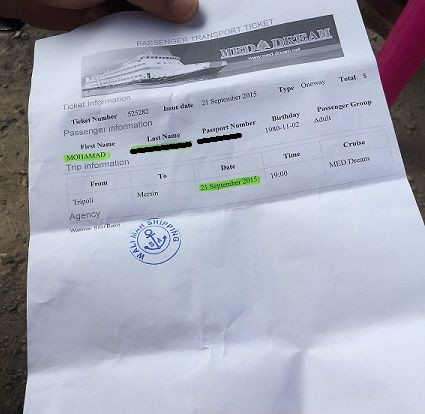

A one-way ticket on an Altair ferry costs $195, and it operates Monday, Wednesday and Friday, according to a company employee. Refugees who travel on Tuesday or Thursday go through Walimar Shipping, another Lebanese transport company that operates ferries from Tripoli to Turkey, at a charge of $180 for a one-way ticket.

For those Syrians who are merely transiting through Lebanon, Altair provides mediation services at the border. Though the trip is legal, some refugees worry that purchasing a one-way ticket will arouse suspicion at immigration control in both Turkey and Lebanon. When asked if this could be a problem for Syrian refugees, an employee of Altair responded that it wouldn’t be an issue if travelers have passports valid for the next six months, since getting documents stamped at immigration “is our responsibility.”

Passengers are required to book their trip from Syria before their departure so that Altair can provide their names to Lebanese immigration for assured entry. Refugees who choose this itinerary are sometimes charged an extra fee, Abdullah said.

Only Altair’s Damascus office, once one of 16 in Syria, remains open after the Syrian government shut the others down for allegedly lacking the required business permits. Despite this setback, Altair is going from strength to strength. The company now provides buses for refugees coming in at two Lebanese border crossings.

Altair has outsourced some of its newly booming refugee operation to local businesses, including Abdullah’s mechanic shop next to the Tripoli port. Abdullah’s storefront is decorated with the German, Turkish, Greek and Italian flags, which he initially said were souvenirs from the 2014 World Cup. Later he admitted that he hung the flags when he started working with Altair, helping refugees book ferry tickets and acting as a middleman between them and immigration authorities.

When refugees arrive at the port, they go to see Abdullah with their passports. He then contacts the nearest Altair office so an agent can collect the documents to get them stamped at Lebanese immigration. Once the documents have been approved, the agent brings everything back to Abdullah, who then distributes tickets and passports to the refugees. Abdullah gets a cut of Altair’s profits, but would not disclose how much, insisting it was minimal.

“I’m making a small amount of money from the tickets,” Abdullah said. “But I’m making more money when they come and sit here and buy things.”

That’s what Hanan’s family is doing at another makeshift café set up on a patch of pavement in front of the port’s entryway. By lunchtime several other Syrians have joined them at the neon plastic tables.

Hanan’s mother Rand is spreading luncheon meat, bought at the café outside the port, on a cracker for Hanan. Her husband, Morhaf, is smoking a nargileh, a water pipe common to most households, cafés and restaurants in both Syria and Lebanon. Later they planned to go to a nearby convenience store to buy food for their long trip to Turkey.

Rand, a native of Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, and a former bioengineering student, is simply relieved to have escaped. She introduces her daughter to the other Syrians sitting outside the port and tells her to wave. It’s less than a day since they’ve left home, but they couldn’t stop smiling. Their ferry to Turkey is not scheduled to leave for another 12 hours, but Rand is prepared to wait at the port all night if that’s what it takes to leave, she tells IBT.

“I’m so happy. If anything happens, I can swim,” Rand said. “I was poor in Aleppo and I can’t take it anymore.”

In addition to the privations of war, Syrians must contend with exorbitant living costs that are unaffordable for even the most affluent Syrians.

“Things got much worse now in Aleppo; we have no water, no electricity, no gas and no diesel. The cost of living is so high, but there’s nothing to do to make money,” said Morhaf. “You’re not safe anywhere in Syria, but the main reason we’re leaving is the living situation.”

Morhaf graduated from a university where he studied to be an architect, but he made a living selling pharmaceuticals because he couldn’t find a job in his field when the war began. The situation is now even worse and three months ago, a lack of customers forced him to shut down his business. Morhaf put his family’s house up for sale in Aleppo and cashed out what remained in his bank account. He changed his money into U.S. dollars to ensure he had enough cash for the various companies and smugglers that would demand payment on his family’s trip from Syria to Europe.

Syrian currency isn’t accepted in most countries or exchange bureaus, which means the majority of refugees are forced to travel with their savings in cash.

Mikaeel Zaitoon, 27, borrowed some $5,000 from relatives to flee Syria. Sunday morning, he took four taxis from Beirut to reach the port in Tripoli, a roughly 1.5-hour ride, and arrived several hours before the ferry’s scheduled departure time.

“Life is a disaster [in Syria]. We had hope that the situation was going to get better, but things are getting worse. Everything is expensive. You can’t afford anything,” Zaitoon said. “We have no electricity and no diesel. They even cut down all the trees in my village for heat this winter.”

Traveling with large sums of cash means most refugees choose to brave the perils of the refugee route to Europe in large groups to avoid robberies. That risk means most refugees travel light. Zaitoon is not even bringing his cell phone.

“I heard a lot of stories of robberies. I know it’s very dangerous carrying $4,000 to $5,000 in my pocket, but there’s no other choice,” Zaitoon said. “I will find another way to get in touch with family because I don’t want to bring anything with me.”

Zaitoon chose to book a hotel room in Tripoli for a week, which gave him a weeklong entry visa to Lebanon, and then bought a ferry ticket that cost $220. His hometown outside of Homs has been under control of Syrian President Bashar Assad’s regime since the start of the war and has seen little violence. Despite the relative safety of his Christian village, Zaitoon fled Syria because he had recently been called up for military service. Not wanting to risk death or endure killing his countrymen, he decided to escape.

His journey so far has been straightforward. “When you pay money, everything works out,” he said.

But by 3:30 p.m. on a Sunday, Zaitoon is still waiting at the port for three relatives who had left Syria at 7:30 a.m. They were on their way to Tripoli to join him on the ferry to Turkey, but were stuck on one of 13 buses filled with refugees waiting at the border. The trip on one of these privately owned buses costs roughly 5,000 Syrian pounds -- less than $30.

None of the Syrians waiting at the port had plans to remain in Turkey, and all hoped to reach Europe. Hanan and her parents and Zaitoon and his relatives would go their separate ways; each had a family member or close friend waiting for them who promised to help find a way to Europe.

“I know someone in Greece, a family member who’s going to introduce me to a smuggler,” Zaitoon said. “Even if the war ends, I’m not going back. I hate it there now.”

The ferry didn’t end up leaving Tripoli until 12:30 a.m. (instead of the scheduled 7:30 p.m.) the next morning and arrived in the Turkish port of Mersin that night. The trip was long, Rand said, but she was pleased Hanan had slept most of the way. Their escape to Europe was delayed after family members in Turkey explained the many dangers of such a trip.

Moftar isn’t too bothered by the delay -- he sees this journey as a temporary fix until the family can return to Syria. He hopes to return once the situation has settled, which is why, he says, he’s rented his home rather than sell it. But his wife disagrees; for her Europe is the only secure place to live now.

“We don’t have anyone there anymore. You’re going back?” she asked her husband with a scoff. “I’m not going.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.