Taliban’s Differences From ISIS Are The Key To Its Success In Afghanistan

BEIRUT — For Kabul’s residents, springtime in Afghanistan brings three things: sunshine, rain showers and blood.

Over the past two decades, the end of winter has been marked by a renewed campaign of violence from the Taliban. The deadly tradition continued this year with Tuesday’s suicide bombing in the capital during morning rush hour. At least 64 people died and hundreds more were injured in a targeted attack in close proximity to the Ministry of Defense and other military compounds.

The explosion cleared the way for Taliban fighters to enter the area and initiate a fierce gun battle with Afghan security forces, a planned assault that followed a statement from the group published on its official propaganda website, Voice of Jihad, a week earlier: “With the advent of spring it is again time for us to renew our jihadi determination and operations.”

The Sunni militants have kept to their word, but this season of bloodshed is likely to be the most lethal yet because the armed insurgents are not the only jihadis in town.

The Islamic State group, also known as ISIS, is a relative newcomer to Afghanistan, declaring its presence by forming Khorasan province in December 2014. The declaration came at vulnerable time for the Taliban, which had recently confirmed the death of its founder and spiritual leader, Mullah Mohammed Omar, killed in Pakistan the previous year. Mullah Akhtar Mansour was chosen to replace him, with the backing of Al Qaeda’s global leader, Ayman Zawahiri. But even with Zawahiri’s support Mansour was not immediately accepted by some prominent Taliban leaders, who expressed their displeasure at Mansour’s appointment by defecting from the Taliban to ISIS.

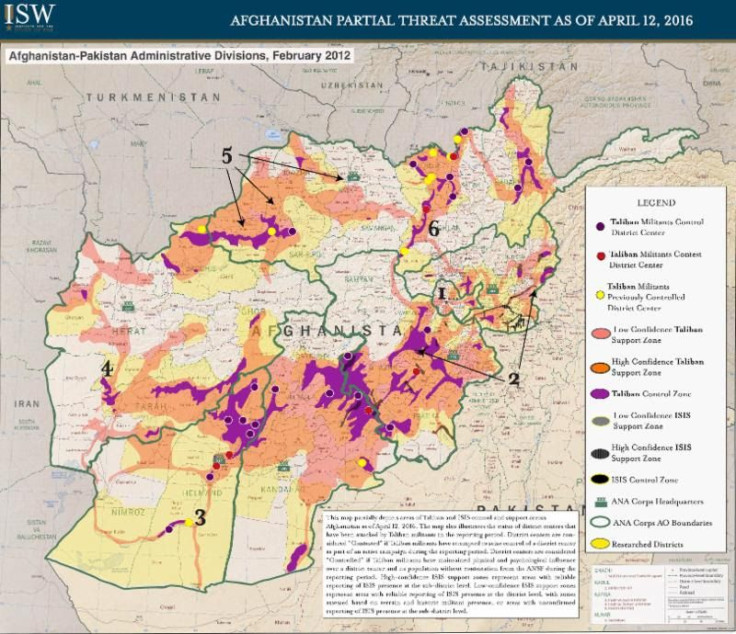

Part of ISIS’ success in recruiting fighters and absorbing existing groups is that it is appealing to an audience that wants to be a part of its so-called caliphate. For this to be sustainable, the group needs to control territory and win over support — by force if necessary — from the local population. But ISIS’ strategy hasn’t been as effective in Afghanistan, where the Taliban has undisputed territory to govern.

The Taliban governed almost the entire country from 1996 to 2001 until the U.S. led an invasion of Afghanistan to oust the armed political party. Since then, the Taliban’s main goal has been to overthrow the current government and rid the country of foreign forces. After President Barack Obama announced in 2014 that the U.S. would slowly be withdrawing its troops from Afghanistan, the resulting power vacuum enabled the Taliban to consolidate its position.

The group controls large swaths of the country — roughly 80 of Afghanistan’s 400 districts, according to the Long War Journal. ISIS has not been so successful — despite carrying out its first large-scale operation in January, in an attack on the Pakistani consulate in Jalalabad, the group has not been able to secure the territory or support needed to defeat its more established rivals.

Taliban fighters, fiercely tribal, are trained and educated by the group’s leaders from childhood. In contrast to ISIS, which will allow anyone to join, so long as he or she pledges allegiance to its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, an individual cannot simply decide to join the Taliban. To the Taliban, ISIS is a foreign entity trying to control Afghanistan, something the Taliban will not accept. ISIS claims primacy over other Sunni extremist groups and hopes to absorb them, but the Taliban is not looking to become a branch of ISIS’ global network, so it believes the two cannot coexist.

Last week, the Taliban issued a statement claiming that several (unnamed) members who formerly defected to ISIS had rejoined the insurgent group “due to the ambiguous blind policies of Daesh ... in short, not having a remedy for the wounds of the Afghans,” the statement said, using the Arabic acronym for ISIS.

“The defections spell problems for the Islamic State, which has struggled to gain a foothold in both Afghanistan and Pakistan,” according to the Long War Journal. “For the Taliban, the reunion with old members ... is a further strengthening of the group.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.