Tax Policy Center Says Romney Tax Plan Still Doesn't Add Up

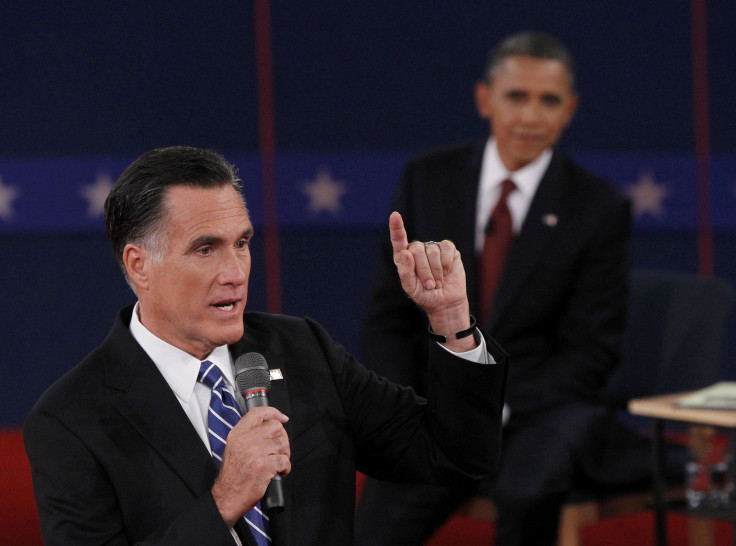

Mitt Romney may have insisted “the numbers add up” while discussing his tax reform proposal during the second presidential debate, but on Wednesday the Tax Policy Center released yet another analysis that concludes it is mathematically impossible to put the GOP presidential nominee’s plan in place without either raising taxes or adding to the federal budget deficit.

The nonpartisan organization completed an updated examination of the plan after Romney, during Tuesday night’s debate at Hofstra University, suggested he could pay for most of the rate reduction and other tax cuts in his proposal by imposing a $25,000 cap on itemized tax deductions.

To review: Romney wants to lower all individual rates by 20 percent and cut the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 25 percent while also completely eliminating the estate tax, the Alternative Minimum Tax and capital gains taxes. And the former Massachusetts governor is also committed to extending the Bush-era tax cuts for incomes above $250,000.

Romney has pledged to do that without adding to the deficit, raising taxes on the middle class or reducing the tax burden on the most affluent Americans.

According to the Tax Policy Center, while capping deductions could potentially raise revenue in a progressive way, it really depends on how high that cap is and whether deductions would be phased out entirely -- as Romney suggested during the debate -- for high-income taxpayers. But on its own, the strategy would not raise enough revenue to compensate for the slashed income tax rate.

“Suggesting limits on deductions was Governor Romney’s first public statement about how he might offset the revenue lost by cutting tax rates. Without more specifics, we can’t say how much revenue such limits would actually raise,” reports the organization. “But these new estimates suggest that Romney will need to do much more than capping itemized deductions to pay for the roughly $5 trillion in rate cuts and other tax benefits he has proposed.”

Romney has, at various points, proposed capping deductions at $17,000, $25,000 or $50,000. Because itemized deductions tend to disproportionately benefit high-income taxpayers (who can claim more), the authors of the analysis concluded Romney’s proposed cap would raise revenue in a “highly progressive” way. But that doesn’t change the fact that it would not create enough additional revenue to offset his proposed tax cuts.

The center reports a $25,000 cap would raise revenue about $1.3 trillion over a 10-year period, covering roughly a quarter of the 10-year cost of Romney’s tax plan. If that cap was set at a tighter $17,000, $1.7 trillion would be raised, while a $50,000 cap would bring in $760 billion.

The Romney campaign has called the new report “misleading and deceitful.” Pierce Scranton, the campaign’s economic policy director, in a blog post questioned the legitimacy of the study and claimed the Tax Policy Center “completely ignored any impact that increased economic growth would have.”

Romney has often said he expects part of his tax cut would be paid for by additional revenue created as a result of the faster economic growth those cuts would encourage. But economists have disagreed about whether a cut like the one proposed by Romney would increase that kind of growth.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.