Technology Focus: Don’t Forget The Chips

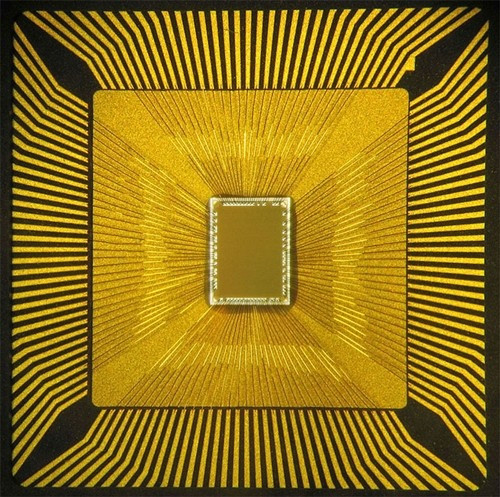

Amid the hoopla surrounding new product introductions by Apple (Nasdaq: AAPL), the initial public offering of Facebook (NYSE: FB) and what's new with Angry Birds, people forget to acknowledge the true brains of the whole business: the chip.

Consumers take for granted the applications on their desktop PCs with Internet access, audio and video, access to printers and the telecom network. Young people have no idea what life was before 1985, when the first U.S. mobile phone service began.

Credit the chip. Whether it was the x86 architecture devised by both Intel (Nasdaq: INTC) and Advanced Micro Devices (NYSE: AMD) or the Motorola 68000 processor designed into the first Macintosh, credit the semiconductor industry for just about all of it.

The industry, valued last year around $302.7 billion by the Semiconductor Industry Association, expects about 4 percent growth this year, with a better 2013, when revenue may reach $328.1 billion.

Considering that Intel by itself last year accounted for $54 billion in total revenue, its market power can't be underrated. Look at its shares: Over the past year, they've gained about 38 percent and 45 percent since 2007. That's without the current 21 cent-a-share dividend.

By contrast, shares of IBM (NYSE: IBM), the No. 2 computer company as well as one of the biggest chipmakers, have gained 29 percent over the past year and 116 percent since 2007.

Big Guns Exited the Field

There are handful of other huge chipmakers, such as Samsung Electronics, surely the most dynamic and impressive performer over the past 30 years; Texas Instruments (NYSE: TXN), Freescale Semiconductor (NYSE: FSL) and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing, which account for a greater share of global demand than ever.

Not long ago, AT&T (NYSE: T), General Electric (NYSE: GE) and Hewlett-Packard (NYSE: HPQ) made their own chips, but the research and development bill, coupled with the costs of building a new wafer fabrication plant, now topping $4 billion, made them quit.

Intel has been investing a fortune as it shifts to its smallest-ever Ultrabook chips in New Mexico. In Malta, N.Y., a $4.6 billion plant owned by GlobalFoundries of Abu Dhabi is shipping its first chips to IBM and AMD.

Will there be drawbacks from this concentration of manufacturing?

For some, like Intel, it looks as if marketing power will only increase. International Data Corp. estimates its share of the microprocessor sector last year was 80 percent, followed by AMD's 20 percent. That kind of power could lead to antitrust problems.

The next drawback is intellectual property. So many U.S. chip companies send all of their designs to Asian foundries like Taiwan Semiconductor or Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. in China that there will likely be serious IP leakage.

Not long ago, the pre-divestiture Motorola had to jump through barriers in Washington in order to sell some old manufacturing machines to SMIC; Washington worried about technology transfer and possible IP theft that could leave the U.S. chip sector vulnerable.

Mastering the Process

Of course, the chips and designs aren't the only knack: Chipmakers and their staffs need to master the process, which only gets more intricate as dimensions shrink. All the stolen IP in the world, say, wouldn't teach North Korean tyros how to copy Samsung's memory chips.

For years, semiconductor designers have pondered whether Moore's Law -- the number of transistors on an integrated circuit will double every 18 months -- can remain viable. The law's named for Intel co-founder Gordon Moore.

Each time it appears miniaturization has reached its limit, some new development inspires hope.

Whether it's new proof that quantum computing is viable at incredibly cold temperatures or a trillion-bit chip can be constructed from old 90-nanometer products, there's hope that the breakthroughs of great technologists like John Bardeen, William Shockley and Jack Kilby nearly 60 years ago will continue into the 21st century.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.