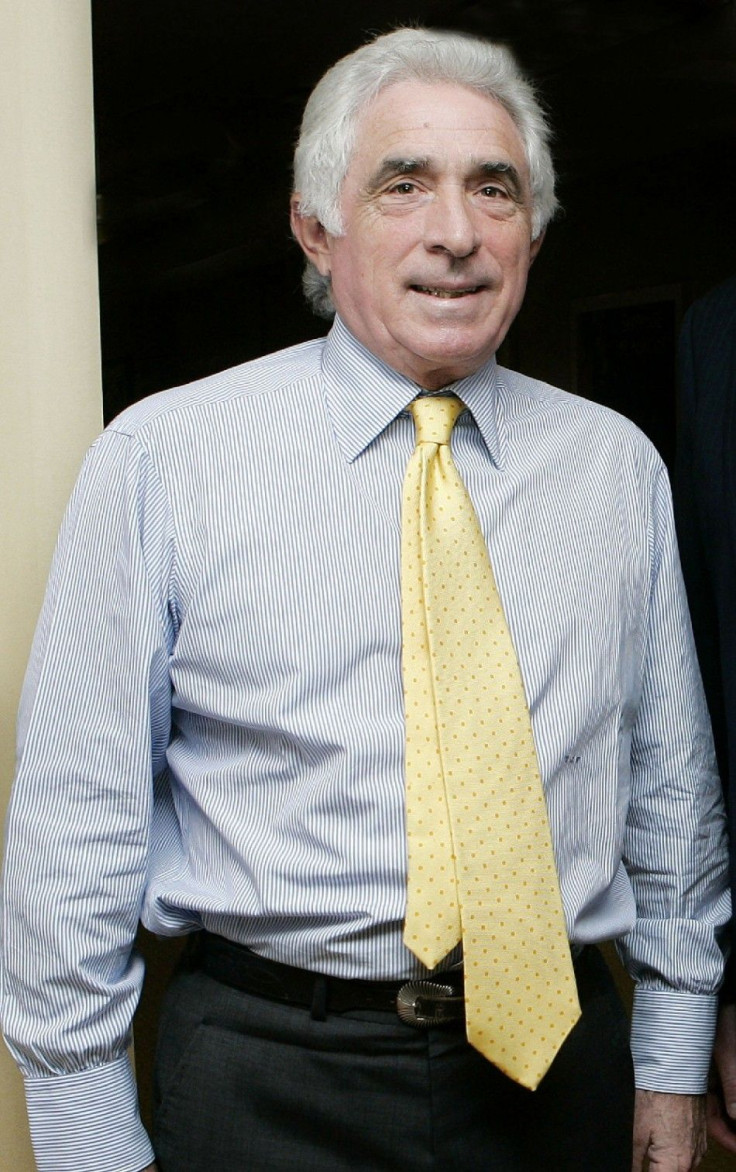

Ted Forstmann, Private Equity Pioneer and Philanthropist, Dies at 71

Ted Forstmann, a businessman and philanthropist who pioneered private equity and rubbed shoulders with Wall Street, Washington and Hollywood over his colorful life, died Nov. 20 at age 71 of brain cancer, his spokesman said.

Theodore J. Forstmann, who lived in Manhattan, was diagnosed with a malignant glioma earlier in 2011.

Private Equity Pioneer

One of six children, Theodore Teddy Forstmann grew up in Greenwich, Conn. as one of six children. Escaping an alcoholic father whose wool business went bankrupt in 1958, Mr. Forstmann played ice hockey at Yale, staying a lifelong sports fan, and put himself through Columbia law School with proceeds from gambling on bridge.

That competitive edge stuck with him. In the 1970s, Mr. Forstmann was one of the first executives to use debt to acquire a company, fix it and then sell it for millions-and sometimes billions-in profit. He bought companies by pooling money from wealthy investors, with large pension funds to back his acquisitions, taking 20 percent of the end profits.

This business model would go on to become known as private equity industry. Over the next three decades, Mr. Forstmann would buy, sell and turn around many dozens of companies, including Golfstream, Dr. Pepper and General Instrument.

Yet as buyout strategies grew in popularity, the mega-successful head of Forstmann Little & Company, founded with his brother Nicholas and investment banker Brian Little, grew more and more cautious about the industry. He began to call the heavy use of debt wampum and funny money.

In a 1988 op-ed in The Wall Street Journal, Mr. Forstmann criticized the rampant growth of fast buying and selling, and the relative inexperience those playing with millions of dollars seemed to be displaying.

Watching these deals get done, he wrote, is like watching a herd of drunk drivers take to the highway on New Year's Eve.

Hisprivate equity firm had a long stretch of beating his rivals, with over an annual average rate of return of 55 percent a year on its equity funds through 2001.

Outspoken Critic of Wall Street Excess

Once I decide to do something, I want to win in the worst way, Mr. Forstmann told the Washington Post in 1995. I will do anything within the law to win. His favorite sports, he said, were golf, tennis and deals.

Despite the cutting edge he brought to business however, the finance pioneer also believed in the importance of caution and moderation in the business world. He quickly became known who fighting rivals who financed their bids with high-yield, high-risk deals called junk bonds.

He believed the junk bonds perverted not only the LGBO industry, but Wall Street itself, Bryan Burrough and John Helywar wrote in their book Barbarians at the Gate, a phrase Mr. Forstmann himself coined.

The problem with junk bonds, in Mr. Forstmann's view, was that it worked on a system of continued indebtedness, paying interest in additional bonds and with soaring interest rates. He saw the phenomenon, which began in the 1980s, as a symptom of a greater problem on Wall Street.

Today's financial age has become a period of unbridled excess with accepted risk soaring out of proportion to possible reward, he wrote in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal in 1988. Every week, with ever-increasing levels of irresponsibility, many billions of dollars in American assets are being saddled with debt that has virtually no chance of being repaid.

A Downward Turn

Mr. Forstmann spent decades at the top of his field, his firm untouched by any financial fluctuations.

The start of the 21st century however, saw two telecommunications investments, XO Communications and McLeodUSA, go bust. Mr. Forstmann blamed himself for the investments, saying he delegated responsibility too much to those in the younger generation, whose fascination with the Internet he found baffling.

All these psychoanalytical things have been written about me that I'm insecure, Mr. Forstmann mused, in an interview with The Times. Maybe I'm very insecure. I thought the world had passed me by, O.K.? I really did. I didn't understand a word they were talking about. I don't use a computer today.

In 2004 the state of Connecticut, which had a pension fund invested in Forstmann & Little from the two busted 2011 investments, sued Mr. Forstmann for the loss of funds, alleging that his investments were too risky and beyond the scope of the type he promised to make. A jury found for the state but awarded no damages.

After the ruling, Mr. Forstmann announced that his current fund would be his last, saying he had become disappointed with the industry and its focus on size and fees.

The world has gone in a completely different direction, the private equity pioneer said. It is not for me. Even if things had never changed, I wanted to stop years ago.

Over the past seven years, he worked steadily on his last big investment: IMG, a sports, fashion and media agency representing celebrities like Tiger Wood and Roger Federer.

Wall Street Philanthropist

Mr. Forstmann joined many in the Wall Street circuit by being involved in politics, hobnobbing with Washington insiders and donating vast sums of money to Republican candidates and causes.

The private equity pioneer was co-chairman of George H.W. Bush's reelection campaign in 1992, and named several prominent Republican allies to run the businesses his firm acquired, including Donald Rumsfeld and Colin Powell as chief executive and board member at General Dynamics in 1990.

Mr. Forstmann was unusual in the Wall Street set however, for being an outspoken philanthropist, giving millions to found and support several prominent charities.

Almost all Mr. Forstmann's charity work centered on children and education, with the philanthropist being among the first to push for voucher programs and charter schools in the 1990s. In 1992, he founded Silver Lining Ranch, a camp for terminally ill kids, and for 25 years held a prominent charity tennis tournament called Huggy Bear at his summer home in Southampton, N.Y., raising over $20 million for children's charities.

In 1999, he co-founded the Children's Scholarship Fund with John T. Walton, the son of Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton, to get underprivileged children into private schools. Mr. Forstmann gave $50 million to get the charity started.

Mr. Forstmann was even more unusual among Wall Street philanthropists however, for reaching beyond Manhattan. In 1994, he flew to Bosnia to deliver millions of dollars' worth of medical supplies and emergency service personnel during the Bosnian War.

Earlier this year, Mr. Forstmann also signed the Giving Pledge, started by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates. The Giving Pledge is a promise by some of the nation's wealthiest people to give away at least half of their fortunes.

Gossip Rag Regular

Far more unusual than his extensive philanthropy work however, was the legendary financier's presence in the media circuit, from appearances on gossip pages to high-profile relationships with Hollywood stars.

He had a brief relationship with Diana, Princess of Wales, which he later said turned into a long-term friendship. Mr. Forstmann, who never married, was often been photographed arm-in-arm with an actress or model, including Elizabeth Hurley and Padma Lakshmi.

Mr. Forstmann had a complicated view of his bachelor lifestyle. In an interview with The Washingtin Post in 1995, he said he struggled with the idea of marriage, and said he would make a difficult husband.

He sees things differently, and that's part of his genius and part of his problem, you know? Barbara Hackett, a former girlfriend, explained in a Times interview in 2004.

Survived by Adopted Children, Siblings

The financier apparently split from Padma Lakshmi earlier this year, and never expressed any wish to marry before he died.

Mr. Forstmann did however, state his desire to adopt children in the 1995 Post interview. Two years later, after speaking with Nelson Mandela at the South African parliament on democratic capitalism, the financial wizard became involved in Mandela's orphanage work and met a young boy named Everest.

This kid is for me, that's it, he recalled about the moment they first met. In another visit two years later, he met another boy, Siya, who had become close to Everest. He brought them both to live with him in New York and became their guardian.

Mr. Forstmann is survived by Siya and Everest, and by siblings J. Anthony Forstmann, John Forstmann, Marina Forstmann Day and Elissa Forstmann Moran. His brother Nicholas died of small-cell lung cancer at age 54.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.