Totally Standard Hyperinflation

SO the FEDERAL RESERVE's second-round of quantitative easing, announced on November 3rd, was a shoo-in - a fait accompli - already decided when the policy team first sat down the previous day, writes Adrian Ash at BullionVault.

How come? As the minutes released this week show, Brian Sack - manager of the New York Fed's System Open Market Account (SOMA) - opened the meeting. And asked to judge the matter, he told the 64 other policy-wonks gathered in the Eccles Building that his team could purchase additional longer-term Treasury securities at a pace of about $75 billion per month while avoiding disruptions in market functioning.

Moreover...

Implementing a sizable increase in the System's holdings of Treasury securities most effectively likely would entail a temporary relaxation of the 35% per-issue limit on SOMA holdings under which the Desk had been operating.

Hey presto! The following day, and after apparently intensive debate, a monthly target of $75 billion in Treasury bond purchases - plus a relaxation of the 35% limit on Fed holdings of any particular bond issue - was announced.

Does that make the Fed meeting a sham? No matter. It's not as if the Fed is doing anything radical, says Princeton professor Paul Krugman. It's simply looking to boost the flow of economy-wide spending by changing the mix of privately-held assets, agrees Berkeley professor Brad DeLong.

It buys government bonds that pay interest in exchange for cash that does not. That is totally standard.

But totally standard where, exactly?

Sure, buying and selling government debt in the open-market is how central banks control short-term interest rates. That's why the Fed Funds rate is a target, and the actual outcome in the marketplace is instead known as the Effective Fed Funds. Bidding short-term bills higher (or lower) in price, the New York Fed thus pushes down (or up) the interest rate paid on those bills. But stuffing the market with money, in contrast, is a very different aim. Not least when you do it by buying longer-term bonds. And by only buying, rather than fine-tuning purchases with sales. And by doing it amid the heaviest net issuance of government debt in history. And by doing it so hard that, despite that record issuance, you still need to break your own limit on the proportion of any individual maturity-date you're allowed to own.

So again, we ask here at BullionVault: Where in the world is such money creation totally standard...?

I think using quantitative easing is a perfectly legitimate thing to do. And for heaven's sakes, it's not as if we're in any danger of inflation any time soon.

- White House advisor and former director of the Congressional Budget Office, Alice Rivlin, speaking to CNBC on 15 November 2010

We have no 'dangerous flood of paper'...On the contrary, our paper [money] circulation, though it shows a terrifying array of billions, is really not excessively high...

- Vossische Zietung newspaper, 16 August 1922

Several [Fed policy] participants saw a risk that a further increase in the size of the...monetary base could cause an undesirably large increase in inflation. However, it was noted that the Committee had in place tools that would enable it to remove policy accommodation quickly if necessary.

- Federal Reserve minutes from 3 November 2010

Even if the quantity of money were three times its present size, it would constitute no real obstacle to stabilization...

- Berliner Börsener newspaper, 18 August 1922

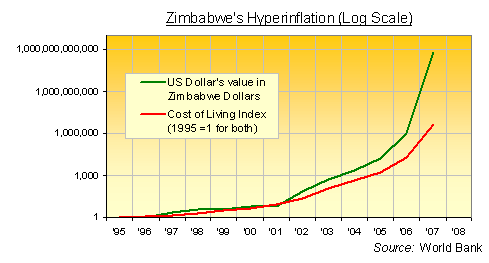

Okay, so pasting a couple of quotes next to each other doesn't mean the United States is headed straight for wheel-barrows and stormtroopers. Like everyone agrees, 1,000,000% inflation looks a long way off right now. But no central bank ever began a hyper-inflationary policy because it feared inflation. Such disasters always come because of vanished credit and economic depression. And whether in Germany nine decades ago, or in Argentina twenty years back, or in Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwe around the turn of this century, stuff actually gets cheaper - not more expensive - in real terms during hyperinflation. It's just that the local currency falls in value faster still, turning the money illusion we're all prey to into a livid nightmare.

Hence the daily flood of French citizens across the border at Strasbourg each day during the early stages of the Weimar madness, emptying the stores with their highly-prized Francs. Hence the real-estate bargains snapped up by wily speculators during Argentina's last-but-one collapse. Hence the zero-change in inflation - net net - for US Dollar earners during the early phase of Zimbabwe's hyperinflation, followed by massive a deflation, in US Dollar terms, even as prices in the local currency soared.

On the ground, amidst these crises, it was monetary contraction - not soaring prices - that most worried policy-makers. The lack of money [now] has a worse effect than the devaluation itself, said one Berlin newspaper in summer 1922, as the Weimar Republic began to run the presses 24/7.

The government printed notes to satisfy everyone, writes Adam Fergusson in his history of the disaster, When Money Dies, telling itself that as the granting of credit...had so greatly decreased, the actual currency in circulation had to be so much greater.

But let's not get perverse. The latest flat-lining in America's official Consumer Price Index does not mean that hyperinflation is in fact underway. The critical factors to watch out for remain a collapse in tax revenues, plus demands for immediate payment from foreign creditors. It bears repeating nevertheless, however, that - contrary to the worldview presented by academic economists and professional wonks - demand-push inflation is not how hyperinflation begins. Real values in fact fall as a genuine currency crisis takes hold.

And the fact that the Federal Reserve is so dead-set on its emergency response that it scarcely needs to meet to agree it, doesn't mean the Fed actually knows what it's doing.

Ready to Buy Gold today...?

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.