Trappist-1 Exoplanets Have Too Much Water, Could Alien Life Survive There?

Water is widely considered to be one of the key ingredients of life. However, in the case of exoplanets such as those orbiting the ultra-cool red dwarf star Trappist-1, the presence of water in abundant amounts could likely be detrimental to the appearance or sustenance of alien life.

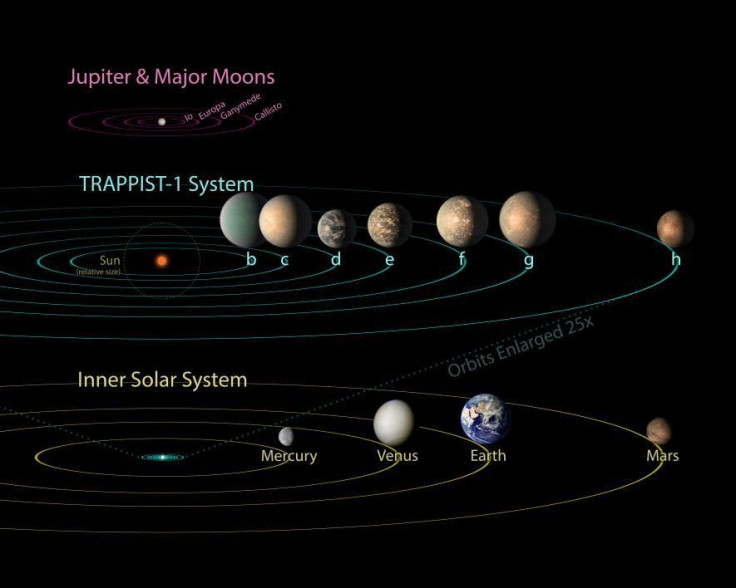

The discovery of Trappist-1, which is slightly bigger than Jupiter and is located in the Aquarius constellation, around 40 light years away from our sun, excited researchers, especially after seven exoplanets were spotted orbiting the star. Researchers have yet to find a planetary system with such a large number of exoplanets.

A team of interdisciplinary researchers, studying the Trappist-1 planet’s habitability, discovered new details about its composition. The research team, consisting of geoscientists and astrophysicists from the Arizona State University (ASU) and Vanderbilt University, found that the planets have an abundant low density component.

Although in the case of most other alien worlds, this low density component would consist of atmospheric gases, researchers believe that in the case of Trappist-1 planets, this component is likely water.

"TRAPPIST-1 planets are too small in mass to hold onto enough gas to make up the density deficit,” geoscientist Cayman Unterborn said in a statement. “Even if they were able to hold onto the gas, the amount needed to make up the density deficit would make the planet much puffier than we see.”

In order to ascertain how much water is present on the Trappist-1 planets, the researchers used a custom-developed software, created by Unterborn and fellow researcher Alejandro Lorenzo. The software, dubbed ExoPlex, makes use of state-of-the-art mineral physics calculators and allowed the researchers to combine all of the available data on the Trappist-1 system.

This data, which includes information relating to the chemical make-up of the star and more, was harvested from a data repository called the Hypatia Catalogue. The database was formed by the new study’s co-author Natalie Hinkel. It consists of information on the stellar abundances of stars close to our sun, derived from over 150 literary sources.

The scientists discovered that the comparatively “dry” Trappist-1 exoplanets, located close to the host star were found to contain less than 15 percent water by mass. However, the outer planets in the planetary system were found to have over 50 percent water by mass. To put this in perspective, Earth has 0.02 percent water by mass. In other words, these alien planets have enough water to make up hundreds of Earth-oceans.

“What we are seeing for the first time are Earth-sized planets that have a lot of water or ice on them,” said Steven Desch, an astrophysicist at ASU and co-author of the new study.

Researchers also discovered that the Trappist-1 planets are actually much closer to the host star than the “ice line”. In every solar system, the ice line is the distance from the star, past which water exists as ice and can be accreted into the planet. However, within the ice line, water exists as vapor and won’t be accreted. This allowed researchers to determine that the Trappist-1 planets likely formed far away from their host star and later migrated closer, before settling in to their current orbits.

“The earlier the planets formed,” Desch said, “the farther away from the star they needed to have formed to have so much ice.”

The Trappist-1 exoplanets are about the same size as Earth and are terrestrial in nature, which ideally makes them potentially optimal sources of possible habitability. Previous studies have indicated the presence of water in these alien worlds, which has led to speculation about whether these planets could host alien life.

However, the findings of the new research indicate that despite water’s life-giving and supporting qualities, an overabundance of it on Trappist-1 exoplanets could make it highly unlikely for scientists to find any evidence of extraterrestrial life.

“We typically think having liquid water on a planet as a way to start life, since life, as we know it on Earth, is composed mostly of water and requires it to live,” Hinkel said. “However, a planet that is a water world, or one that doesn't have any surface above the water, does not have the important geochemical or elemental cycles that are absolutely necessary for life.”

Although there may be no alien life on the Trappist-1 planets, scientists still hope to be able to study them further to better understand how such icy worlds are formed and what kind of planets could be better candidates in our search for life in space.

The new study was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.