Trump’s New Iranian Oil Sanctions May Inflict Pain At Home

The Trump administration has formally imposed new sanctions on Iran aimed at hindering Iran’s oil exports – a move that had been in the works for six months.

The U.S. government has also made a second, more surprising, announcement: It’s granting eight countries waivers that will let them keep on buying Iranian petroleum.

Since I’m a historian of energy and U.S.-Iranian relations, I’ve been monitoring how the Trump administration’s policy toward Iran has affected global oil markets. I believe that these new sanctions do not serve U.S. energy interests because they may spark price increases that would punish American consumers. More generally, this move illustrates what I see as the incoherence of Trump’s energy policies and international diplomacy.

Taking aim at oil exports

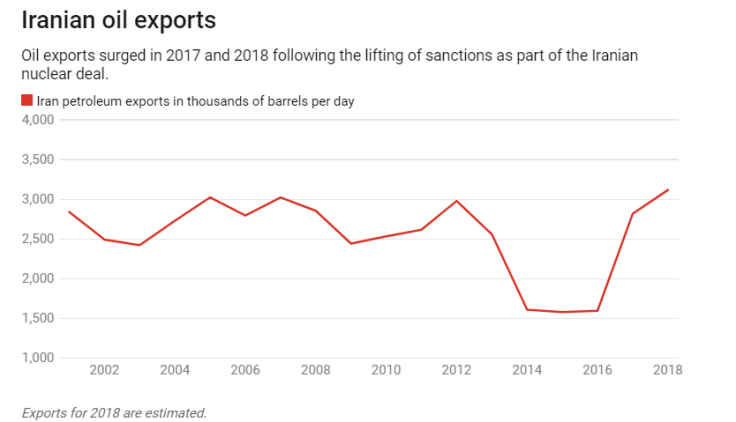

Since Iran first became a major oil producer in the 1930s, its government has depended on oil and gas revenue for most of its budget. When the Obama administration imposed tough economic sanctions on Iran in 2012, to force Tehran to the nuclear bargaining table, the Middle Eastern country’s exports declined sharply.

The U.S. lifted those sanctions after Iran agreed to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, an international agreement that placed restraints on Iran’s nuclear program. As a result, its overseas oil sales shot up in 2016 and 2017.

But now President Donald Trump, who has derided the agreement since his electoral campaign, is bringing the hammer back down.

Shortly after withdrawing from the nuclear deal in May 2018, the administration announced that it would re-impose sanctions and attempt to reduce Iran’s oil exports to “zero.”

Trump’s team also vowed that it would retaliate against any countries that kept buying Iranian oil after Nov. 5. Iran’s oil exports then slid from 2.6 million barrels per day to about 1.7 million by September.

Panic over prices at the pump

The administration claims that it wants to change Iran’s behavior and that the sanctions are intended to pressure the Iranian government to stop supporting terrorism. Many analysts have speculated that the U.S. intends to exert pressure on Iran until the regime collapses.

Sanctions may bring about pain and suffering for the Iranian people, but I agree with other experts who doubt that they will weaken the most entrenched and conservative elements of Iran’s government – let alone dislodge its leadership.

What’s more, negotiators of the original nuclear accord doubt that Iran will agree to anything new. It’s more likely that further confrontation with the U.S. will strengthen Iranian hardliners and neuter chances of further negotiation, just as heightened tensions doomed talks between George W. Bush’s administration and the reformist government of Mohammad Khatami in the early 2000s.

Regardless of the political effect on Iran, Trump’s effort to squeeze Iranian oil exports have affected global oil markets.

The reduction in Iranian shipments has put pressure on global oil prices, propelling them for a while above US$80 a barrel for the first time in four years. Oil prices then tumbled once the Trump administrated granted the waivers. U.S. gasoline prices were falling when the sanctions were imposed yet averaging $2.74 per gallon, which is higher than they’ve been in years.

Trump has fumed about this spike, blaming the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries for not pumping enough to meet worldwide demand.

But OPEC is not responsible for this upswing. Its members have been producing more oil lately to make up for declines in Iran and Venezuela. In fact, its spare capacity, which could be vital in the event of a major disruption, is running low.

Saudi Arabia claims it can pump an extra 2 million barrels per day. But data from the Energy Information Administration indicates that Saudi Arabia will only have the potential to increase its daily production by 1.2 million barrels in 2019. That’s a dangerously slim margin.

Energy dominance

The Trump administration has an insurance policy against the tightening oil market: its “energy dominance” policy and higher domestic production levels.

Domestic production has doubled in a single decade, thanks to a boom in drilling that began during the Obama administration following groundwork from George W. Bush’s presidency.

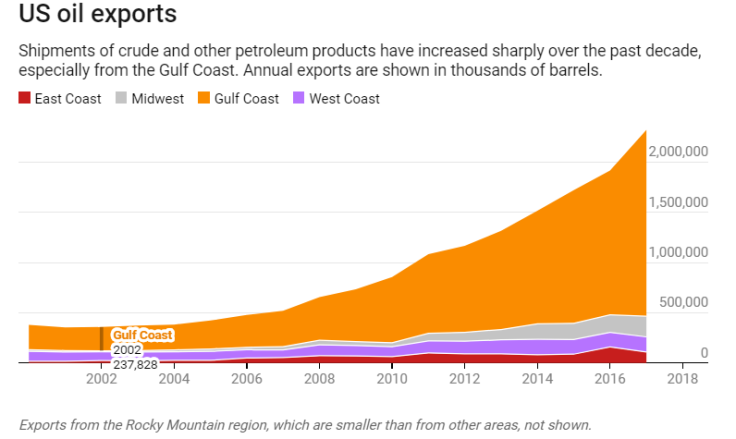

Crude oil exports are way up too, thanks to the repeal of a 40-year ban on most of those shipments in late 2015.

With domestic production booming, there’s a chance that the U.S. could be insulated from shocks to the global oil market.

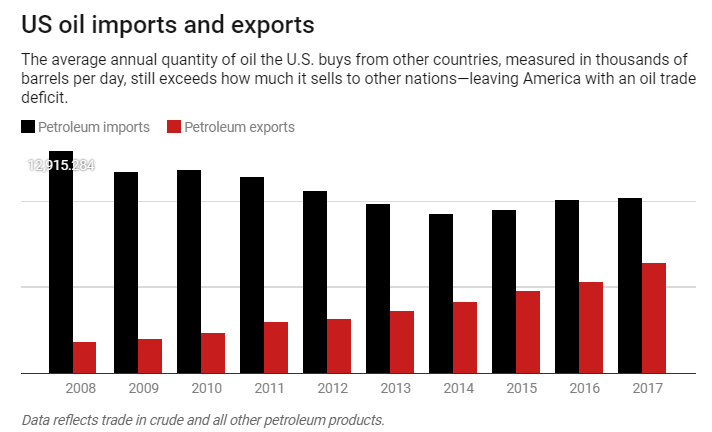

But compared to Saudi Arabia, Russia and other major producers, America still sells relatively little crude to other countries and it imports far more oil than it exports.

What’s more, U.S. oil comes from hundreds of smaller fields, which makes it hard to easily cut or increase output. As a result, the notion that the U.S. can serve as a “swing producer” to restrain global oil price volatility is, in my opinion, unrealistic.

One way that the Trump administration could help is by encouraging energy conservation. Instead, it’s done the opposite by encouraging more fossil fuel investment than ever. Developing more oil fields may boost U.S. production, but it will also deepen American dependence on gasoline and diesel, making the U.S. economy more vulnerable to disruptions in the global market.

No end game

So why did the Trump administration give eight of Iran’s biggest customers, China, South Korea, Taiwan, India, Greece, Turkey, Japan and Italy waivers?

Perhaps it recognized the risks tied to squeezing Iran’s oil out of the markets altogether. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that waivers were granted after each country promised to continue cutting Iranian imports over time.

Trump has admitted that he was “going a bit slower” on Iran. “I don’t want to lift oil prices,” he said.

He took this position despite reported protests among Iran hard-liners like National Security adviser John Bolton. Pompeo, another hardliner, defended the waivers as part of a broader strategy of pressure on Iran. He rejected the idea that this was a retreat.

Whatever the intent, this move did soothe fears of a supply shortage.

With these waivers in place, Iran’s oil exports are likely to rebound slightly in the coming months.

But should the Trump administration change course again, cutting off much more of Iran’s access to global oil markets at a time when the world’s spare capacity is dangerously low, it could lead to much higher gas prices in the U.S. and elsewhere.

And that’s the fundamental contradiction at the heart of U.S. oil policy. Punishing Iran by choking off its access to global petroleum markets will end up punishing U.S. consumers. They will have to pay more at the pump and higher oil prices will make just about every purchase more expensive.

Gregory Brew is a postdoctoral fellow at Center for Presidential History, Southern Methodist University.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the original article here.