US Is In Recession, Says Noted Economist; Why The Obama Economic Recovery Plan Has Faltered

Forget the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Ignore the S&P 500. The records that they’ve recently set, although impressive at first blush, tell us almost nothing about the state of the U.S. economy.

Indeed, the U.S. is four years into a rebound from a recession that began in 2007 and ended some 24 months later, and still some of the most important economic metrics -- those that affect individuals much more than the performance of the stock market does -- are below pre-recession levels; in other words, this is a slow, febrile recovery unlike any before.

“It is unprecedented this far into an expansion to have all these major components still making up for lost time,” said David A. Rosenberg, chief economist and strategist for Gluskin + Sheff Associates Inc.

He’s talking about, for example, employment numbers. The March report issued by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed an abysmal 88,000 jobs created; but worse yet, total employment remained at about 3 million less than pre-recession levels. Moreover, participation in the labor force fell to 63.5 percent, the lowest it's been since 1979.

But employment numbers are just the beginning; the weakness of this recovery infects virtually every important aspect of the economy:

· Annual median household income fell to $45,018 in 2012, down from $51,144 in 2010, according to the Census Bureau.

· Factory output fell 20 percent from late 2007 to June 2009 and by last month had recovered only about three-fourths of this decline, the Federal Reserve reports. In addition, the Fed notes that production of consumer goods in the U.S., which decreased 14 percent during the recession, is still at about half of its pre-recession peak.

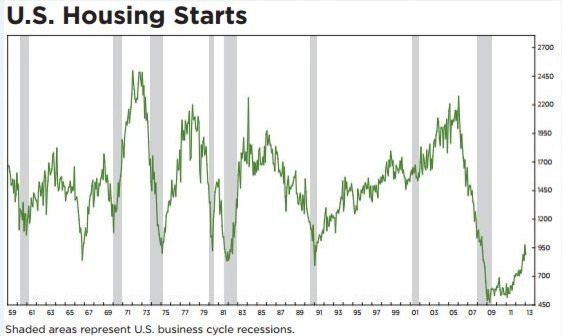

· Existing home sales on an annualized basis are 10 percent below their highest levels, and new home sales are down by nearly 20 percent.

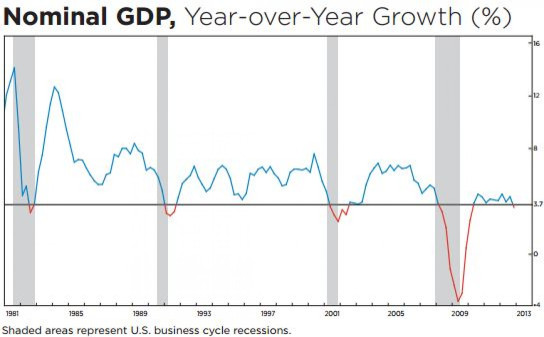

· Growth in the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) is actually slowing, the opposite of what would be expected in a recovery. In the last three months of 2012, U.S. GDP grew an anemic 0.1 percent. For all of last year, the GDP was up only 1.7 percent. By contrast, in 2011, U.S. GDP climbed 2 percent, and in 2008 it was up 2.2 percent.

These numbers are clearly not what the government bargained for when Washington pumped trillions of dollars in taxpayer money into the economy to turn it around. On the monetary side, the U.S. Federal Reserve has slashed interest rates by purchasing huge amounts of bonds and other forms of debt in hopes of giving businesses cheap money with which to expand and hire new workers. At the end of last month the Fed had $3.25 trillion of debt on its books, up from about $800 billion at the end of 2008. And on the fiscal side, President Obama pushed through in 2009 an $800-billion-plus stimulus package, a mixture of tax cuts and job programs.

Still, despite the cheap and loose money, private sector job creation has lagged. And although the White House promised that the government’s economic growth strategies would cut unemployment to nearly 5 percent, from 8.3 percent in 2009, unemployment kept rising that year to 10 percent in October and only recently has slowly descended to its current 7.7 percent.

Faced with this unusually weak recovery and the government’s relative impotence, at least one team of economists who carry a significant amount of weight believe that the U.S. is, in fact, in recession -- perhaps not the garden variety recession we are used to (namely, two consecutive quarters of declining gross national product) but a recession nonetheless.

This group, the Economic Cycle Research Institute (ECRI), a non-partisan outfit that forecasts turning points in economic growth and inflation, defines recession as “a self-reinforcing downturn in economic activity, when a drop in spending leads to cutbacks in production and thus jobs, triggering a loss of income that spreads across the country and from industry to industry, hurting sales and in turn feeding back into a further drop in production.”

Or, put less technically, a vicious cycle. Based on this definition, “it is ECRI’s view that the economy is currently in a recession that began in 2012,” said Lakshman Achuthan, ECRI Chief Operating Officer, in an email to International Business Times.

According to a paper Achuthan wrote last month, after the U.S. came out of the housing bubble recession, the economy proceeded to zigzag until it fell into a backward trajectory around the middle of last year.

Among the many metrics that Achuthan used to reach his conclusion that the U.S. has descended back into recession are the weak recent GDP numbers. In the last 65 years nominal GDP growth below 3.7 percent always occurred in a recessionary context, “without exception,” according to Achuthan. In other words, 3.7 percent GDP growth is an economy’s virtual stall speed, below which it cannot climb or even maintain level flight. Yet, by the middle of last year, year-over-year nominal GDP growth had slipped to 3.5 percent.

In addition, Achuthan points to a slightly different measure used by the Fed: gross domestic income (GDI), or the amount of money that producers get for their products or services. When the annualized GDI growth rate falls below 2 percent, it often means the country is in recession. In the second quarter, 2012 GDI growth dipped to 1.5 percent and in the next quarter it dropped further to 0.4 percent.

In Acuthan’s view, three other essential indicators -- industrial production, personal income and sales -- peaked last summer and “U.S. job growth is worsening, not getting better,” he says.

“We are not seeing signs of an imminent growth upturn that so many claim to see,” the report concludes.

ECRI is in the minority in saying that the U.S. is in recession currently, but the group’s conclusions shouldn’t be taken lightly, no matter how unpopular those conclusions are. They’ve been accurate before when others thought differently. Here’s what the New York Times wrote in 2011 about ECRI: “Over the last 15 years, (ECRI) has gotten all of its recession calls right, while issuing no false alarms.”

In many ways it doesn’t matter if the U.S. is in recession or not; after all, even the economy’s most optimistic observers are having a difficult time putting a rosy hue on its recent performance. So, if there is at least consensus among economists that serious challenges remain before the U.S. can return to full economic health, two critical questions are raised:

· Has the federal government failed in its efforts to overcome the worst downturn since the 1930s or is the U.S. and indeed the rest of the world facing structural and fundamental economic forces that are impossible to mitigate with old ideas?

· What should businesses and investors do in this type of confounding economic environment?

As the slow recovery or recession tightens its hold on the U.S. economy, an increasing number of experts are reaching the conclusion that Washington bears some blame for the failure of the economy to rebound. For one thing, they argue, the government’s spending initiatives have diverted capital from employers and entrepreneurs. And the Federal Reserve’s lavish money printing has buoyed too-big-to-fail banks, super-charged U.S. stock markets and punished savers -- while failing to lend to businesses sufficiently enough to grow the economy substantially.

And then there is the proliferation of costly regulations. The Obama administration has approved far more than [George] Bush did in his first three years in office. According to a report from the [White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs] report, Obama approved 37 “major” regulations between Jan. 20, 2009, when Obama was sworn into office and Sept. 30, 2011, including 29 that cost more than $100 million, according to FactCheck.org. "During a similar span at the start of the Bush administration, Bush had approved nine — six of which cost more than $100 million. The estimated cost of Obama’s major regulations also far outweighed the cost of major regulations approved by Bush, $18.8 billion to $4.3 billion," FactCheck.org said.

It estimates that the cost of Obama's major regulations cost $18.8 billion, compared with $4.3 billion for Bush.

Indeed, the World Economic Forum noted Washington's increasing tendency to meddle in the business sector when it explained why it lowered its rating of the U.S. over the last three years from No. 2 to No. 5 in its annual ranking of global competitiveness. “The business community remains concerned about the government’s ability to maintain arms-length relationships with the private sector and considers that the government spends its resources relatively wastefully,” the WEF wrote.

This point of view is amplified by Salim Furth, a senior policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation, who attributes the economy’s continuing weakness to high fixed costs, which inhibit startups -- the main source of new hiring -- from taking on more workers. “With new regulations and business requirements in health insurance, small-business finance, environment, energy and tax compliance, not to mention the ever-expanding reach of state licensure boards, it is expensive to open a business,” he writes. “High fixed costs and onerous regulations are textbook ‘barriers to entry.’”

To be sure, more liberal, Keynesian economists, who believe that government spending is a strategic weapon in the fight against unemployment and stagnation, contend that the Obama administration and the Fed have not gone far enough to jump-start the economy with their stimulus and monetary initiatives.

"After successfully arresting the economy’s free-fall with expansionary fiscal and monetary policy, policymakers’ failures on the fiscal side have exacerbated the anemic economic recovery in the United States,” said Andrew Fieldhouse, federal budget policy analyst with the progressive Economic Policy Institute, who has elaborated on his views in a paper with co-author Josh Bivens.

“The United States is mired in a liquidity trap and depressed $975 billion (5.8 percent) below potential output -- in this context expansionary fiscal policy is the only means of ensuring a full economic recovery and avoiding a Japanese-style lost decade (we’re already half way there in terms of output, more than a decade there in terms of middle class incomes)," he said. "The pace of trend U.S. economic growth has markedly decelerated as expiring fiscal stimulus has been replaced with austerity, and growth prospects for 2013 imply renewed labor market deterioration, particularly if sequestration remains in effect.”

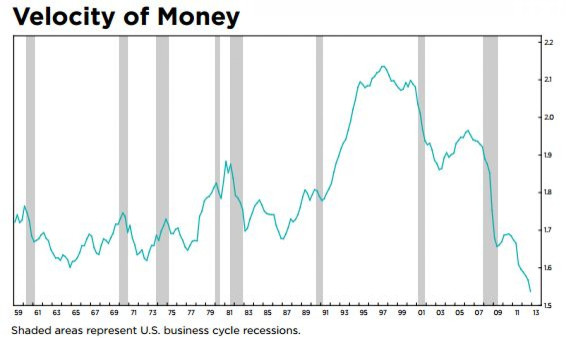

But while there is some historical evidence for the effectiveness of that type of approach, much of it is decades old, coming from a time when the U.S. had an insular economy and virtually every dollar rolled into the money supply stayed in the country to pay for consumer purchases, personal and corporate investments, wages, and commercial or agricultural production; this government money directly impacted economic growth. In a globalized economy, however, Keynesian principles are not that easy to apply effectively as they once were.

For example, when the government pours money into the economy now, much of it ends up being spent on products made in other countries; in a sense, the money is exported, often to return to the U.S. as currency used by overseas investors to buy American treasury bonds that fund the deficit. That’s the simplest illustration of globalization’s impact on national economies and how difficult it is these days to address local economic concerns with local and traditional solutions.

Add to this the complexity and interwoven relationships involved in international derivative transactions, currency swaps and other tangled and unfathomable equity and capital arrangements, and it’s little surprise that government economic policymakers are increasingly feeling hamstrung and powerless.

The impact of globalization has produced an intriguing but little-known long-term drift toward economic weakness in the developed world that takes at least some of the heat off the government for its inability to drive greater growth over the last four years.

At least since the 1970s, because of structural changes in global economic fundamentals, “growth in GDP and jobs has been stair-stepping down in successive economic expansions,” ECRI’s Achuthan told IBTimes. He elaborates on this in a 2012 study and concludes that the U.S. economy and its cousins in Europe can expect more frequent recessions in the future followed by less than satisfactory rebounds.

That may offer some answers to economists like Gluskin + Sheff's Rosenberg, who are perplexed by the current weak recovery despite economic activity that would have in the past generated robust overall gains.

“This includes the wealth effect [from the stock market]," says Rosenberg, "the wonders of shale gas; the manufacturing renaissance; more than four years of 0 percent policy rates; and a tripling of the Fed balance sheet. This includes all the bailout stimulus. It includes the ballyhooed housing recovery. And it includes four straight years of $1 trillion deficits. Epic.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.