Vocational Education May Be Better Strategy Than College For Many Americans: Study

More Americans have college degrees than ever before, but a new paper suggests college may not be the best strategy for many young people.

A new working paper from the Cambridge, Massachusetts-based National Bureau of Economic Research suggests that some Americans may be better off attending vocational school than a four-year college. The four researchers compared the U.S. education system with Germany’s, highlighting the European nation’s widespread vocational education programs.

Germany’s Success

The general conclusion of the paper is that “improved access to better vocational education can probably contribute more [to the lives of lower-income people] than large increases in college attainment.” Within “the lower end of the income distribution,” the authors suggest, vocational training helps prevent job losses and lessens income inequality more effectively than four-year college education. “Pushing more students to degree-granting colleges may not be an efficient way to deal with the declining real incomes of the working poor,” write authors Joshua Aizenman, Yothin Jinjarak, Nam Ngo and Ilan Noy.

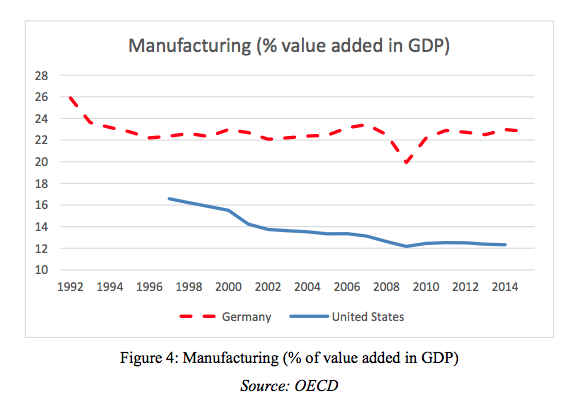

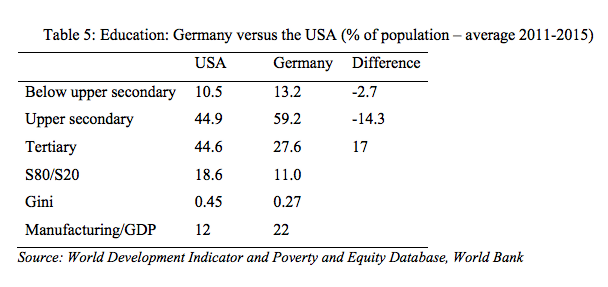

The paper, which also compares Thailand with Vietnam, focuses mainly on the differences between Germany and the U.S. Germany, like the U.S., has suffered job declines in manufacturing. But Germany’s manufacturing sector, the authors found, was able to weather the 2008 global financial crisis far better. In fact, despite job losses, manufacturing’s share of the country’s gross domestic product is back where it was before the recession, and worker productivity has increased. Meanwhile, manufacturing’s share of GDP in the U.S. has steadily declined; its share (12 percent) is roughly half of that in Germany’s (22 percent).

Technological advances have likely contributed to this discrepancy. But another key variable is the level of education obtained by the workers. Germany has a rate of “upper secondary,” or vocational, schooling that’s 15 percent higher than in the U.S., but the rate of “tertiary,” or four-year college, education is 17 percent lower.

The unemployment rate in Germany is at 3.6 percent, lower than the U.S.’s 4.2 percent.

Mounting Student Debt

One big financial burden on Americans is student debt. Total outstanding student loan debt is a colossal $1.4 trillion. The cost of education in the U.S. is far higher than in many comparable nations, including Germany. The authors find that the costs of attending four-year college in America are often “out of line with the expected employability and the financial return associated with college education,” although this problem is present, to a lesser degree, among two-year public institutions as well.

Plenty of Americans in the manufacturing sector have four-year college degrees, which often aren’t necessary for such jobs. Less expensive vocational school burdens students with less debt and prepares them better for the manufacturing jobs — a better return on investment.

The authors’ conclusion tracks with public opinion trends in the U.S. A recent survey found that 47 percent of Americans (up from 40 percent in 2013) now think four-year college is not worth the cost “because people often graduate without specific job skills and with a large amount of debt to pay off.” Among 18 to 34-year-olds, only 39 percent think four-year college is worth it.

Still, four-year college is emphasized in America, and students considering post-secondary education often aren’t informed of all of their options. At age 10, children in Germany choose an academic high school track, a vocational track, or something in between, but there are opportunities to switch tracks at a later date. While the U.S. system idealizes a four-year college program, Germany’s encourages those who are more interested in trade jobs to pursue those.

“Germany starts identifying students who are struggling in the ‘academic’ track in middle school (7th grade), and has various mechanisms in place to assist these students to succeed in [vocational employment training] programs,” write the authors. The country also has successful apprenticeship programs.

Germany has significantly lower income inequality than in the U.S. According to the World Bank, Germany has a Gini coefficient — an income inequality measure, with lower numbers indicating lower inequality — of 0.27, while the U.S. has an extremely high 0.45 coefficient, roughly equivalent to the latest figures for Djibouti and Peru, and higher than those of China and Russia. There are many reasons for America’s wide income and wealth inequality, but the authors suggest that a healthier manufacturing sector would mitigate this to some degree.

Surviving Hard Times

Another key conclusion is that a shallow social safety net in the U.S. is the reason manufacturing job losses generated more “social impact” than in Germany. The European nation, which has more robust public programs such as subsidized health care and inexpensive education, is a more hospitable place for the unemployed. The authors note “the first-ever decline in life expectancy in some parts of the US.” The situation in American “may resemble more the dynamics in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union and its own deindustrialization, rather than the dynamics observed in Germany.”

The authors conclude with an interesting political analysis. With fewer manufacturing jobs and expensive health care and education, something has got to give. If countries like the U.S. do not provide adequate vocational training and re-training, they will “either have to rapidly upgrade their safety net to avoid increasing destitution, or to face the consequences of the greater political instability and the social costs associated with the hollowing-out of the middle class — political instability that is most likely associated with such anomalies as the Brexit vote, the U.S. election of 2016, and other recent electoral surprises.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.