Water On Mars: Greenhouse Gas-Fueled Climate Cycles May Explain How Canyons And Valleys On Mars Formed

It is a question that has long vexed scientists studying Mars — how did water-carved canyons and valleys on the red planet form roughly 3.8 billion years ago, when our current understanding tells us that this was a time when the planet was frozen over? The answer, according to a study published in the Earth and Planetary Science Letters, could have to do with dramatic fluctuations in ancient Mars' temperature caused by the build-up of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere.

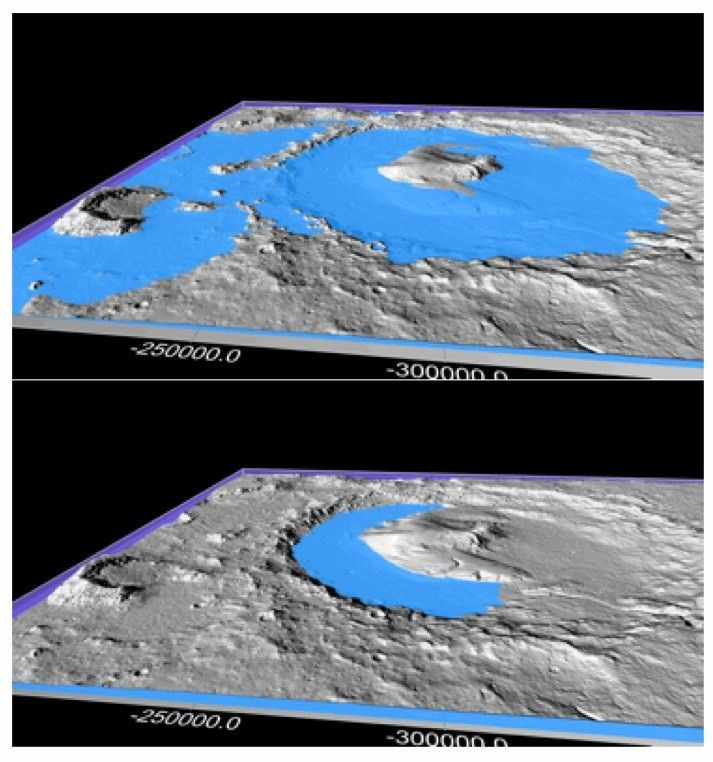

The study, based on climate models of the red planet, suggests that Mars may once have experienced long-lasting cycles of warm periods caused by a thick atmosphere rich in carbon dioxide and hydrogen. These warm periods — some of which are believed to have lasted as long as 10 million years — may have allowed liquid water to flow long enough to create the geological features that are still visible.

"With the cycling hypothesis, you get these long periods of warmth that give you sufficient time to form all the different Martian valley networks," study co-author Natasha Batalha, a graduate student at the Pennsylvania State University, said in a statement.

The researchers believe that the greenhouse gasses in Mars' atmosphere may have come from Volcanic eruptions. As these gasses accumulated in the atmosphere, the greenhouse effect caused the planet to heat up, which, in turn, increased precipitation and returned some of these gasses to the surface. Over a period of time, this process — known as chemical weathering — cooled the planet back down, and ushered in another ice age.

"Mars is in this precarious position where it's at the outer edge of the habitable zone," Batalha said. "It's receiving less solar flux, so you start at a glaciated state. There is volcanic outgassing, but because you are colder, you don't get the same deposition of carbon back into the planet's surface. Instead, you get this atmospheric buildup and your planet slowly starts to rise in temperature."

We already know that Mars, currently a dusty and barren wasteland, was not always so. Data collected by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Curiosity rover has bolstered the theory that roughly 4.3 billion years ago, Mars had enough water to cover its entire surface in a liquid layer about 450 feet deep.

Evidence also suggests that long after solar winds stripped the red planet of its atmosphere, turning it into the cold, arid world it is today, lakes of water and snowmelt-fed streams still existed on its surface.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.