'We Made It': Iraqi Refugee Family Is Home At Last

He sought safety. She wanted freedom. They were dreams they could have died for.

From a first date that ended in bloody carnage in Baghdad, to finally receiving the keys to a new home in The Netherlands, theirs is an epic tale of courage, survival and love.

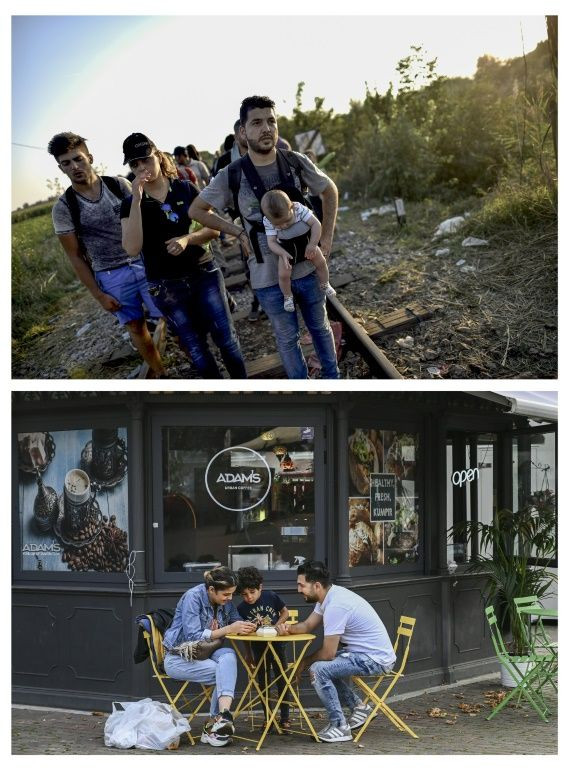

In 2015, with four-month-old Adam strapped to his father's chest in a baby carrier, Iraqi couple Ahmad and Alia, now 32 and 31, joined the million migrants who crossed the Mediterranean to Europe's shores.

They faced death at sea, indignity on the road and a torturously long wait for asylum -- all for a chance at life in "peace and safety" for their child.

One family among so many, an AFP team met them on a sunny day in September 2015 in Gevgelija, a quiet town on the border between what is now called North Macedonia and Greece.

Hundreds of mainly Syrians, Iraqis and Afghans, men, women, children, elderly people, mothers with newborns and war-wounded amputees, all squeezed into a train headed for Serbia and the European Union.

Over five years, three AFP journalists in text, photo and video have followed Ahmad and Alia's every step towards their new life, travelling with them that September by train, bus, smugglers' cars and on foot across borders at night.

Later that year, they caught up with them in a migrant shelter in The Netherlands, where the couple already had family, as they filed their first asylum claim.

Now, as the family settles into life in the eastern town of Duiven, they all meet up again.

Out of concern for the safety of relatives still in Iraq, Ahmad and Alia have asked to be identified by their first names only.

Here is their story.

In August 2019, the phone rings.

Alia answers and receives the earth-shattering news that she has been granted refugee status.

On the other end of the phone, the lawyer who helped her make her claim explains she has won the right of residence and that her husband and son will automatically follow.

Ahmad, who has dark brown hair, and hazel-eyed Alia kiss, celebrating the news that will forever change their lives.

"I shouted, wept and laughed all at once," says Alia. "It was even happier than our wedding day."

It was "the moment we had been dreaming of, right from when we had set out from Iraq," Ahmad says.

Within weeks, the family has residence cards and travel documents. They are no longer undocumented migrants. They have the right to a home, to work and travel.

"At last we could have everything we wanted: a normal life like any other family in The Netherlands," Ahmad says.

The decision to flee Iraq came after Ahmad, then an upscale fashion store owner, took Alia, daughter of a university chemistry professor, to Mr Chicken, a Baghdad restaurant.

It was their first date since becoming engaged in February 2014.

As they ate, a bomb blast tore the place apart. The shards of glass that they say killed other diners have left still visible scars on Alia's face.

"I saw death that day. Had we been sitting at a different table we might not have survived," Ahmad says.

They led middle-class lives and were close to their families.

"I adore my country," Ahmad says, watching a Snapchat video of Baghdad's sun-drenched streets.

But "in Iraq, when you go to work in the morning, you don't know whether you will come back alive."

For the couple, Adam's birth in 2015 brought everything into sharp focus: he deserved better.

Ahmad sold his shop and his share of the property he had inherited to fund the journey ahead.

He had already been a refugee, having fled to Syria with his family like thousands of other Iraqis in 2006 at the height of the sectarian war, only to return six years later when Syria also descended into conflict.

"But year after year, the situation in Iraq just kept getting worse. Corruption and militias took over," Ahmad says.

The rise of the Islamic State group in 2014 and a myriad of powerful armed factions sparked a new wave of displacement, the UNHCR says.

In 2015, 88,757 Iraqis crossed the Mediterranean to Greece and Italy, UNHCR data shows.

As of 2019, there were around 214,000 Iraqi refugees in the European Union.

"We were forced to migrate. We never had a choice," Ahmad says.

Today, the family lives in a two-bedroom house with a brown brick tile roof and a back garden in leafy Duiven, near the Dutch border with Germany.

They have painted the walls white, laid dark brown floor panels, hung rose print curtains, bought Adam a loft bed with a desk and planted tomatoes outside.

For the entrance, they picked a doormat that reads "home".

"We made it," Ahmad smiles, sipping coffee sweetened with condensed milk, rays of autumn light shining through the large living room windows.

Thanks to their new status, the family receives a monthly government stipend of 1,400 euros ($1,630). Duiven town hall gave them a 3,500-euro home improvement loan which they are paying back in monthly instalments.

From their stipend, they pay rent, social security, insurance, electricity, phone and internet bills.

Twice a week, the adults take language lessons at a nearby academy. Their textbooks are in Dutch and Arabic, which helps them learn faster.

Ahmad speaks basic Dutch while Alia just about gets by, though switches into English for longer conversations.

But it is their curly-haired, brown-eyed son who is most in tune with his surroundings.

Adam speaks fluent Dutch, Arabic and English, and says he feels "half-Iraqi, half-Dutch."

Now five years old, he rides his bicycle every morning to the local Montessori school.

Dutch weather permitting, he plays football at a nearby park with his school friends.

Duiven is safe enough to allow the children out alone.

While his early childhood was far from conventional, he is doing well, head teacher Marike Ketelaars says.

"Adam is a child like any other child. He wants to play outside and wants to make friends," she says.

Once he goes to bed, the parents watch Netflix shows like "Game of Thrones" -- with Arabic subtitles to help them keep up.

Until recently, such simple pleasures felt beyond reach.

The couple will never forget the fear and exhaustion of their journey to get there, with the constant dread of failure and having to go back to Iraq.

Most of the 9,000 euros ($10,500) they carried in their backpacks went within a week, largely to smugglers who got them across the Mediterranean, the Serbian-Hungarian border and the Austrian frontier.

The scariest part was crossing into the European Union, as, that autumn, Hungary erected razor wire fences on its border with Serbia to try to stem the migrant influx.

Under the light of a full moon, an Iraqi Kurdish smuggler led the pair and their companions through a field, evading police.

As they followed in silence, the women and children in the middle of the group, they narrowly escaped an ambush, the AFP journalists with them saw, when some men suddenly appeared in what looked like police uniforms.

Several migrants brandished tree branches and the likely would-be thieves vanished again into the darkness.

Alia was terrified every step of the way.

In Budapest, they cradled Adam to sleep in an alley when no hotel or even a brothel would accept their money in return for a room.

When they arrived in The Netherlands, the relief they felt didn't last long.

The next four years were lost in a soulless administrative maze, shifted from one migrant shelter to another, including a former women's prison.

In December 2015, the AFP team visited them in an exhibition centre-turned-shelter in Leeuwarden, in the north.

Their temporary "home" was a plywood cubicle with no door or ceiling.

"This isn't life. How can I explain it?" Ahmad said at the time. "It's like a bird in a cage."

Their relatives in The Netherlands did not give them the welcome they expected, leaving them feeling abandoned to their fate.

While they waited for asylum, they could not earn a living, rent a house or plan for the future.

Much to their shock, two asylum requests were turned down because Ahmad returned from Syria to Iraq in 2012 -- an apparent contradiction with his claim that he is unsafe in his homeland.

They filed appeals on the grounds that neither Syria nor Iraq is safe -- but in vain.

For nearly a year, they lived as undocumented migrants in a string of acquaintances' flats.

"I couldn't do anything that required showing ID," Ahmad recalls. "I couldn't go to the bank, I couldn't take Alia to hospital when she was sick. Everyone I knew looked down on me, like I was less worthy than them."

The anguish of that period weighed particularly heavily on Alia, who suffered stress-induced hair loss.

"There were moments when the pressure was more than I could bear," she says.

Ahmad loves the wet Dutch weather. "This is a beautiful, green country," he says, smoking a cigarette in the garden under the drizzle.

They do most of their shopping at a Lidl supermarket and once a month take the bus to the nearby town of Arnhem to stock up on Arabic bread and spices.

In Iraq, Alia relied on her mum to cook for the whole family. Now, she uses YouTube tutorials to learn how to make both Iraqi and Dutch meals.

Adam's favourite after-school snack is fluffy Dutch pancakes with fruit.

While they are a sociable family, the Covid-19 pandemic has forced them to isolate themselves more than they would have liked.

Nonetheless, they are friendly with other parents at Adam's school, greeting them every day with a smile and a "goedemorgen" (good morning).

Still perhaps in the honeymoon period of their new Dutch life, the pair struggle to find any faults when asked what is strange or difficult.

They have experienced occasional hints of xenophobia -- the odd comment such as "it might be OK where you come from but not here".

And Ahmad questions why they and so many like them had to put their lives on the line just for a shot at applying for residency in Europe.

But since receiving their papers "for the most part, Dutch people have welcomed us warmly," he says.

In 2015, The Netherlands received 58,880 asylum applications, nearly half of them from Syrians, according to the Dutch Immigration and Naturalisation Service (IND).

"Even though we waited for so long to obtain asylum, I don't have any hard feelings towards this country," he says.

"This is the country we have chosen to call home."

Today, Alia is a changed woman from the often hesitant and worried person she seemed during the journey, torn between hope and fear.

All energy, irreverence and spark, she was saved from depression by making friends with a group of Venezuelan asylum seekers and a Polish woman.

With them, she started to see The Netherlands with new eyes, going out and having fun for the first time in years.

"They became my new family," says Alia, a huge Arabic pop and Latin American reggaeton music fan. "We went through everything together -- the good and the bad."

Feeling stronger than ever, she took a leap of faith.

Unlike her husband, she had never left Iraq.

She had also dropped out of high school in Baghdad after Islamists threatened her over her refusal to wear the veil.

With the help of a lawyer, she filed an asylum application in her name, which the authorities accepted.

The longer they're in the country, the wider she spreads her wings. The rental contract is in her name, as are the bank account and household bills.

She is glad to live in a place where women's rights are respected, as she never espoused the Middle East's conservative social mores.

"Here, I am free from all that," says Alia, whose hair is two-tone bleach and brown, like UK pop star Dua Lipa's on the cover of her "Future Nostalgia" album.

Her eyes well up with tears for the relatives she misses in Iraq, but, she says: "I no longer have any regrets."

Alia says she will always be proud of her Iraqi roots, and she passes that pride on to Adam through stories, the use of Arabic at home, and daily Facetime conversations with his grandmothers.

"He will grow up here. But he has to know where he comes from," says Alia, who plans on training as a make-up artist or a hair colour specialist.

Ahmad is now studying for his driving test and dreams of starting his own business, possibly in the transport sector.

"The road ahead is long, but the worst is behind us," he says. "Now, everything is possible."

And Alia is pregnant with their second child, who like its parents will one day become a European citizen.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.