What Are The Chances You'll Soon Encounter A Drone? The FAA, Boeing (BA), Lockheed Martin (LMT) And Northrup Grumman (NOC) Will Help Decide

Inside a dark metal box on the outskirts of Las Vegas, a team of Air Force drone controllers orchestrates a strategic, unmanned strike, killing a car full of Taliban soldiers in Afghanistan almost 8,000 miles away. Then they order pizza, which is delivered to their compound gate by… drone.

Which part of this scenario seems unrealistic?

In fact, both could be true in the near future, though for now it’s more likely that a drone will be used to kill than to deliver a large Meat Feast Supreme.

What began as a secretive military operation at the Ground Control Station at Nellis Air Force Base near Las Vegas -- the center for drone operations in the United States – is in the process of going public in a big way, which has expanded an already divisive debate over unmanned aircraft, for whatever use.

However, whether you believe drones should be used for long-distance killing or short-distance UPS shipments, this much is undisputed: Domestic drones will be a major part of American life in the very near future. The Federal Aviation Administration hopes to draft new legislation governing the use of drones in U.S. airspace by 2015, potentially opening the skies for up to 10,000 long-range unmanned aircraft by 2017.

The United States has actually been slow to enact comprehensive federal legislation governing drone use, though such craft have been put into civilian use elsewhere in the world in the service of agriculture, archaeology, search and rescue, fighting forest fires, wildlife conservation, 3D mapping and even mail delivery, which is a far cry from the craft’s origins as a vehicle for remote-controlled precision ambushes of Taliban fighters in the foothills of the Hindu Kush.

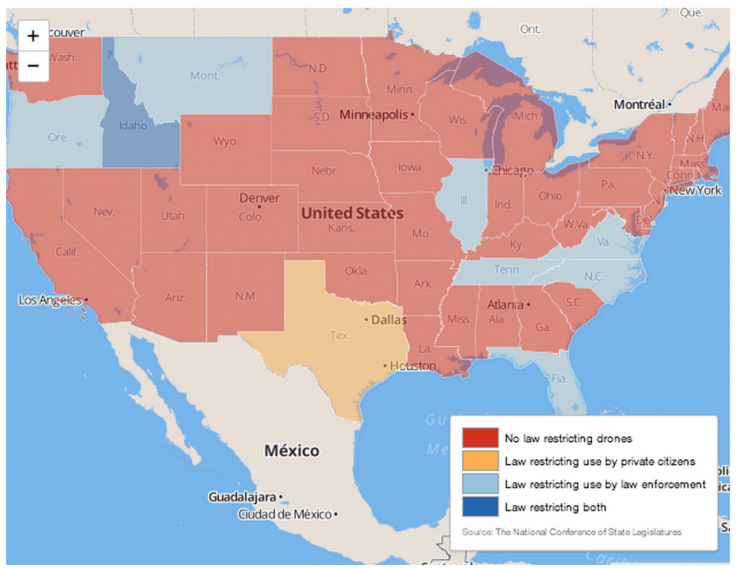

Current U.S. laws governing drones – officially, UAV, for unmanned aerial vehicle – vary from state to state, but federal law already restricts them to flying at less than 400 feet in altitude to minimize interference with conventional aviation. Beneath that height, hobbyists are free to fly what they like, provided the craft weights less than 55 pounds and the operator has the drone in his continuous line of sight.

Essentially, drones are regulated much the same as model airplanes, though they are autonomous (meaning they fly themselves once their destination coordinates are entered), as opposed to remote-controlled aircraft of the type one occasionally sees hobbyists flying over parks. Until more-comprehensive federal rules are established, and unless otherwise restricted by state or local laws, private citizens are more or less free to buy and use drones.

Commercial drone use, on the other hand, has been illegal since 2007. Companies (as well as universities and fire departments) can get around this limitation by convincing the FAA that they have extenuating reasons for using a drone, such as for research or for testing drone products. As of December, there were 545 active FAA releases, most of which were awarded for research and demonstration purposes to academia and drone manufacturers.

It’s unclear what legislation the FAA will propose in 2015, but it will probably include expanded use of drones by law enforcement authorities, which already fly them with some frequency. The Department of Homeland Security loaned to local police departments as many as 700 drones between 2010 and 2012, according to the Electronic Frontier Foundation. And on Jan. 14, 2014, a North Dakota man was found guilty of terrorizing police officers who were trying to arrest him at his ranch in 2011 after a 16-hour standoff that included use of a drone loaned by Homeland Security to observe the armed man and his movements from above using infrared imaging (the first case of a drone helping to arrest a U.S. national).

To use drones, law enforcement authorities also must apply to the FAA for a waiver from current restrictions against non-military and non-civilian operation of the devices. The waiver is not easy to obtain and requires an extensive application to the FAA, which must include a vast amount of technical and operational data, as well as topographical and physical maps of the area where the drone is to be used. Depending upon the application, the FAA may add caveats or rulings, such as that the drone can fly only during the day or below a certain elevation. Opponents of police drone activity, including the American Civil Liberties Union, have called on the FAA to formulate clear and permanent rules that would allow law enforcement to deploy drones only if they are granted a warrant, in an emergency or when there is specific proof that a drone will enable the collection of evidence relating to a criminal act. Also, the ACLU wants to ensure that drones in American skies do not carry weaponry.

Oregon, Montana, Illinois, Tennessee, Virginia, North Carolina and Florida have banned drone use by law enforcement. Idaho has made it illegal for police or private citizens to use drones, and Texas is the sole state to have banned only private citizens. Despite this hodgepodge of rules, most experts say that it is difficult to track questionable or outright illegal drone use, potentially making the FAA’s attempt to regulate the activity moot. For example, in Illinois, where it is illegal to use drones to interfere with hunting or fishing, animal rights group PETA has said it will continue to put drones in the air to harass illegal hunters. After all, a sportsman would be hard-pressed to prove that the drone scaring off the hunted animals came from PETA, or even that there was a drone in the area. Similarly, if a drone appeared in your backyard and appeared to be cruising for who knows what, what is the likelihood it would still be there when the police arrived, or that it would bear markings indicating its owner’s name and address?

The FAA has, in fact, sent out 12 cease-and-desist orders to individuals caught illegally flying drones, but those have involved minor violations. FAA spokesperson Les Dorr said that most commercial drone use was resolved via an informal letter or visit from the FAA. For example, some real estate developers in the U.S. have been told by the agency to stop using drones for photographic surveys of property. A Naperville, Ill., real estate agent resident received an FAA cease-and-desist letter after the agency spotted a video of his on YouTube (a simple search on the site for “real estate drones” brought up nearly 30,000 results).

To some, these relatively innocuous incidents represent the lighter side of a situation that threatens to get out of control in the coming years unless closely regulated. Brian Hearing, co-inventor of Drone Shield, a drone detection technology, told IBTimes that drones have already been implicated in drug smuggling along the southern U.S. border. The Public Security Secretariat of Mexico announced in 2011 that cartels had adopted this new way of sending cocaine to the U.S., though the craft used are not of familiar designs but custom-built to resemble something akin to flying rickshaws. In 2011, the last year for which figures are available from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 223 unknown flights were detected going across the border, double from the year before. Border patrol agents have 10 drones of their own, mostly along the Mexico-Texas border. Could drone air fights in that corridor be far behind?

A 2013 report by the Congressional Research Service titled “Integration of Drones into Domestic Airspace: Selected Legal Issues” warned that “traditional crimes such as stalking, harassment, voyeurism and wiretapping may all be committed through the operation of a drone. As drones are further introduced into the national airspace, courts will have to work this new form of technology into their jurisprudence, and legislatures might amend these various statutes to expressly include crimes committed with a drone.”

Even Hearing acknowledges the potentially insidious nature of private drones. His product, Drone Shield, which detects the noise that drones emit to ensure that they are not used in secret, was hatched when his business partner’s drone accidently flew into a nearby garden and provided unobstructed shots of the interior of his neighbor’s house. The homeowners, meanwhile, were completely unaware that they were being watched.

So far, surveys have found that the American public tends to support the use of drones in foreign combat zones. For instance, a March 2013 Pew Research poll found that 64 percent of Americans favored drone use overseas. Thirty percent disagreed. But it is uncertain how thousands and thousands of drones over the U.S. mainland – and the prospect of all 18,000 police precincts in the U.S. having this equipment – will be greeted.

It may not matter. Drones have the potential to mean big profits in the U.S., which offers businesses – and the government officials they lobby -- real motivation to pursue their expansion. By 2025, the drone equipment business is projected to be worth $82 billion and employ around 100,000 workers, according to the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International. And although the FAA projects that there will be 10,000 drones in civilian use by 2017, some experts say the actual figure will be nearly double that.

Many large corporations have already shown that they are willing to put their money behind an all-out blitz to further legalize drones. In 2013, several drone manufacturers -- Northrup Grumman Corporation (NYSE:NOC), Lockheed Martin Corporation (NYSE:LMT), The Boeing Company (NYSE:BA) and General Atomics -- ploughed nearly $26 million into the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), the lobby that is supporting the advancement of unmanned systems and robotics, according to Opensecrets.org. Medea Benjamin, author of "Drone Warfare: Killing by Remote Control" and founder of Code Pink, a grassroots peace initiative, says the AUVSI pushed Congress to get the FAA to make changes to drone restrictions. “AUVSI is an association of companies, and they’ve become a very powerful lobby and have the ear of Congress and the administration driving this agenda,” Benjamin said.

The payback could be significant: A General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper, which is an unmanned combat drone used by the U.S. military, U.S. Homeland Security, and a number of other countries including the United Kingdom and France, costs more than $11 million.

Still, companies that can afford the devices are already expressing interest in incorporating them into their business plans. E-commerce giant Amazon.com Inc. (NASDAQ:AMZN) and Domino’s Pizza Inc. (NYSE:DPZ) have said that they would launch a drone-based delivery service after the FAA approves these commercial activities. And police departments are getting used to this equipment now; it’s likely that they will invest in newer, state-of-the-art drones as the technology evolves.

If drone use continues to expand and Congress passes related FAA-sponsored legislation, glitches and accidents will inevitably occur, as they did following the invention of the car. And that begs the question of how people will feel about seeing a picture of themselves on the Internet taken by an inconspicuous drone, or if a drone collides with their car, bus or one of the many helicopters that whizz around major cities on any given day. What if someone gets tired of being buzzed and shoots down the offending drone? How about the 400-foot limit when delivering packages to people who live at high elevations? And what even happens to pizza at those elevations?

Those questions remain unanswered, but the chances are we’re going to find out sooner rather than later.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.