What Is An Exocomet? NASA’s Hubble Telescope Found Them Plunging Into A Young Star

It is only 23 million years old, and for a star so young, HD 172555 is seeing some pretty interesting activity: a rain of comets.

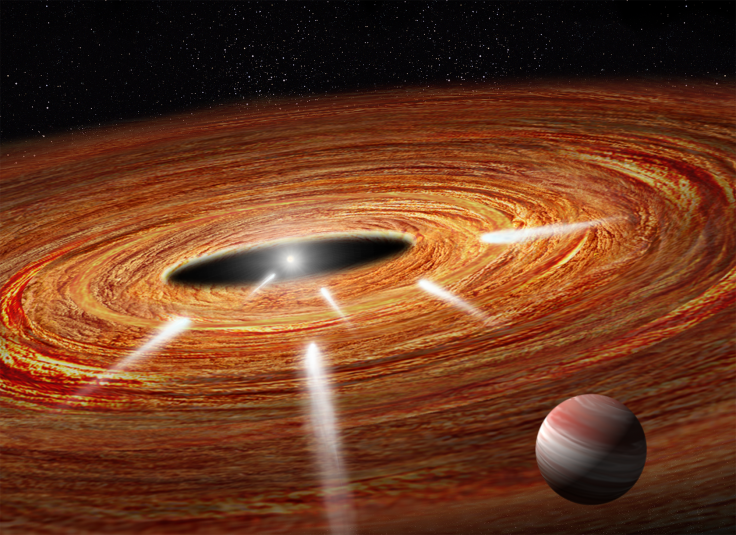

Using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have detected numerous exocomets — comets outside our solar system — plunging into the star which is about 95 light-years from Earth. These exocomets were not seen directly but their erstwhile presence was inferred by the gases their icy nuclei left behind as they vaporized.

Such phenomenon has been observed in two other star systems, both of them under 40 million years old, as well as in our own solar system, which dates back about 5 billion years.

“This activity at its peak represents a star’s active teenage years. Watching these events gives us insight into what probably went on in the early days of our solar system, when comets were pelting the inner solar system bodies, including Earth. In fact, these star-grazing comets may make life possible, because they carry water and other life-forming elements, such as carbon, to terrestrial planets,” Carol Grady of Eureka Scientific Inc. in Oakland, California, and NASA's Goddard Spaceflight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in a statement.

The presence of these comets plunging to their deaths is indicative of “gravitational stirring” by a large Jupiter-sized planet whose gravity deflects the exocomets toward their doom. And the presence of inward-falling comets in other star systems could also mean that similar activity in our solar system was responsible for transporting water to Earth and the other inner planets.

The exocomets transiting HD 172555 were first discovered by French astronomers, who used spectrograph equipment of the European Southern Observatory to detect traces of calcium imprinted in the starlight. Grady’s team, following up on that discovery, found additional signs of silicon and carbon gas in the starlight, moving at about 360,000 miles an hour across the star’s face. And now, her team wants to look for hydrogen and oxygen as well.

“Hubble shows that these star-grazers look and move like comets, but until we determine their composition, we cannot confirm they are comets. We need additional data to establish whether our star-grazers are icy like comets or more rocky like asteroids,” Grady said in the statement.

Grady and her team that made the latest exocomet observations presented its findings at the ongoing 229th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Grapevine, Texas.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.