Which Is The World’s Most Spoken Language? Terpene. What’s That, You Ask?

China, the most populous country in the world, has close to one billion people that speak Mandarin. Spanish is spoken by a less than half that number, primarily in Mexico, Spain and the countries in South America. English follows close behind, with Hindi in India and Arabic in the Middle East making up the top five. Or so you would think.

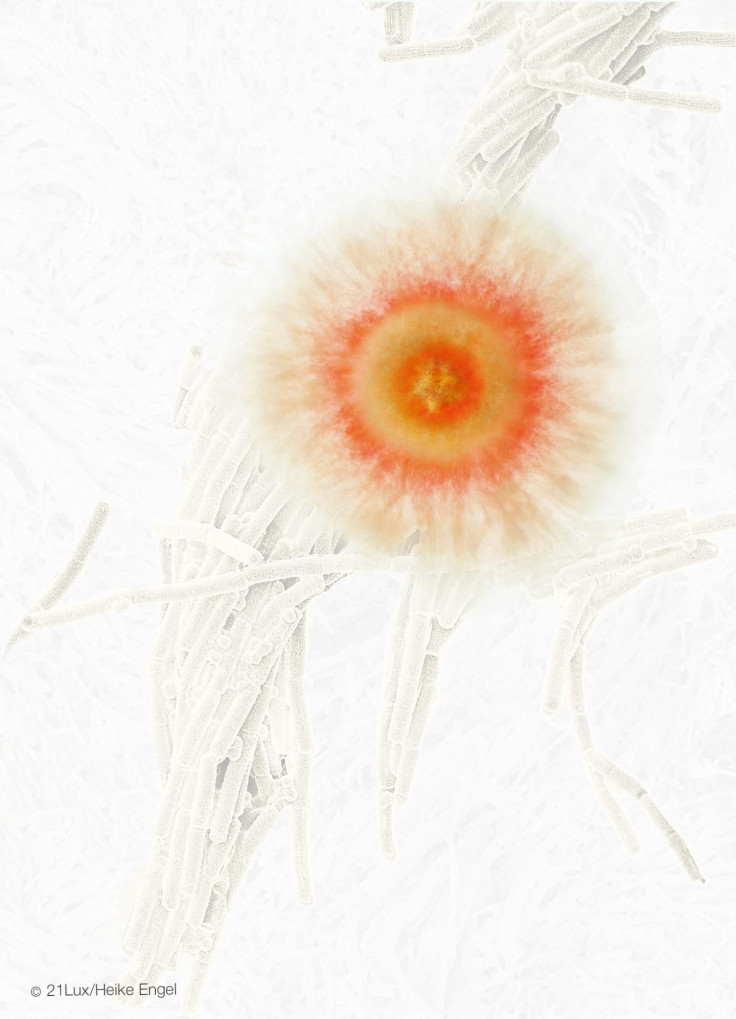

The most common language in the world is actually not human at all. In fact, it is not even spoken. Research has shown that micro-organisms communicate with each other, and that bacteria and fungi — which far outnumber all animals and plants on Earth, by several hundreds of orders of magnitude — talk among themselves and to each other using fragrances, especially terpenes.

Read: Terpene Analysis Helps Identify Marijuana Flavor

Researchers from the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO) and their colleagues published a paper Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports that discusses how chemical communication using smells perhaps works for a very large number of life forms. They also demonstrate in the open-access paper, titled “Fungal volatile compounds induce production of the secondary metabolite Sodorifen in Serratia plymuthica PRI-2C,” that bacteria and fungi respond to each other.

Terpenes are compounds produced by a large variety of plants and fungi, as well as by some insects, and they have long been known as a means of communication between plants and insects. They are a large class of organic compounds that usually have a strong smell, and their applications are being considered in a wide variety of fields, including creation of designer marijuana.

By studying the genes that were expressed in a bacterium, as well as the proteins and fragrance it began to produce, during interaction with a fungus, the researchers arrived at their conclusion.

Paolina Garbeva of NIOO, leader of the research group and one of the senior authors of the paper, explained in a statement: “Serratia, a soil bacterium, can ‘smell’ the fragrant terpenes produced by Fusarium, a plant pathogenic fungus. It responds by becoming motile and producing a terpene of its own. … Such fragrances – or volatile organic compounds – are not just some waste product, they are instruments targeted specifically at long-distance communication between these minute fungi and bacteria.”

Terpenes were not the only volatile organic compound used by micro-organisms to communicate with each other.

Ruth Schmidt, a PhD student under Garbeva at NIOO and lead author of the paper, said: “Organisms are multilingual, but ‘terpene’ is the one that’s used most often.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.