Why Does Turkey Seek A Greater Role In War-torn Libya?

Turkey's parliament approved a security and military cooperation deal with Libya's UN-recognised unity government based in Tripoli on Saturday.

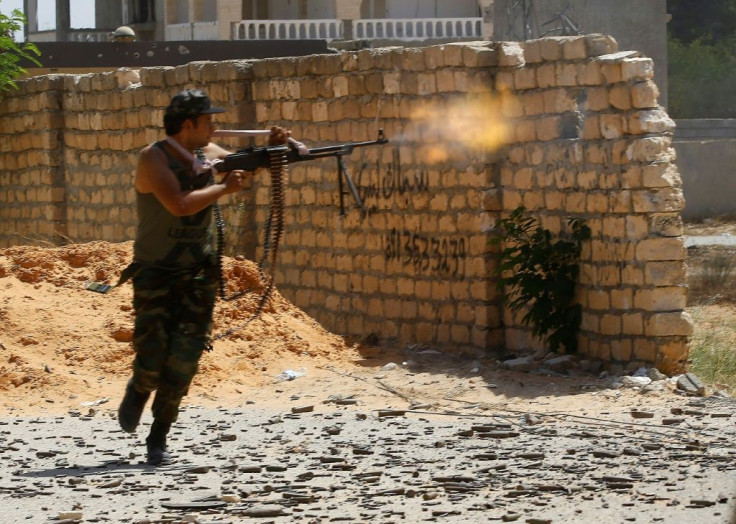

Oil-rich Libya has been mired in chaos since a NATO-backed uprising toppled and killed dictator Moamer Kadhafi eight years ago.

The North African country has since become split between bitterly opposed administrations in the east and west -- each backed by outside powers.

While Tripoli's Government of National Accord (GNA) in the west is supported by Turkey and Qatar, eastern-based strongman Khalifa Haftar has the backing of Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has said Ankara is ready to send troops into Libya if requested by Tripoli, but the current agreement would not allow Turkish combatant forces to go to Libya.

It would however allow military and police exchanges for training purposes and closer cooperation in fields including intelligence, counter-terrorism and defence exports.

While the GNA is desperate to repel Haftar's forces from the outskirts of Tripoli, analysts say Ankara has other geopolitical interests. Here are three questions and answers on the situation.

The GNA, with the support of armed groups from Misrata, 200 kilometres (125 miles) east of Tripoli, has managed to hold off Haftar's troops, who have been trying to seize the capital since April.

But while frontlines are stalemated, Haftar has dominated the skies with Chinese-made Wing Loong drones supplied by his main backer the UAE, according to the United Nations and analysts.

Turkey has sent the GNA Bayraktar drones to counter those of Haftar's forces, but these were low-cost in comparison and many were destroyed, said defence analyst Arnaud Delalande.

Reports say that on the ground, pro-Haftar forces have recently received support from contractors with Wagner -- a private military group believed to be controlled by an ally of Russian president Vladimir Putin. Russia has denied sending mercenaries to fight in Libya.

"The GNA has started to see the risk" that Haftar is gaining the advantage, Delalande said.

Turkey is likely to send the GNA air defence systems, including drone-jamming technology, Delalande said, alongside advisers and more modern drones.

Such support could "rebalance forces" on a battlefield where Wagner has reportedly deployed anti-drone systems that have brought down an American drone and an Italian one, Delalande said.

But Ankara is unlikely to deploy troops or send fighter jets to carry out strikes, Delalande said.

Turkey does not have an air base close enough to Libya to carry out strikes discreetly, as Delalande said the UAE does from Egypt.

Nonetheless, according to Libya expert Emad Badi, Turkish support for the GNA could be a "game-changer, depending on the form of military aid".

"Turkey's alignment with the GNA is dictated by a mix of factors" both geopolitical and ideological, said Badi, an analyst with the Middle East Institute.

Turkey is primarily interested in countering the influence of its regional rivals the UAE and Egypt, who support Haftar and oppose Islamist movements close to Ankara.

But it also has economic and strategic interests in supporting the GNA.

Tripoli recently signed a maritime agreement with Ankara, expanding Turkey's claims over a large area of the Mediterranean.

The discovery in recent years of vast gas reserves in the eastern Mediterranean has put Turkey at odds with littoral states Greece, Egypt, Israel and Cyprus.

While the European Union has threatened Ankara with sanctions for illegally drilling off the coast of Cyprus, Turkey hopes its accord with Tripoli will help legitimate its exploration.

Turkey, which has occupied the northern part of Cyprus since 1974, recently sent a military drone to the island, and has warned that it will block all gas exploration it does not approve of.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.