World AIDS Day 2012: In Nigeria, A Matter Of Time And Money

The West African colossus of Nigeria, already burdened by militant violence, widespread poverty and endemic political corruption, is also beset by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. At least 3.3 million people in the country are suffering from the disease – the second-largest such absolute figure in the world, after only South Africa.

As in South Africa, the numbers are stark and sobering.

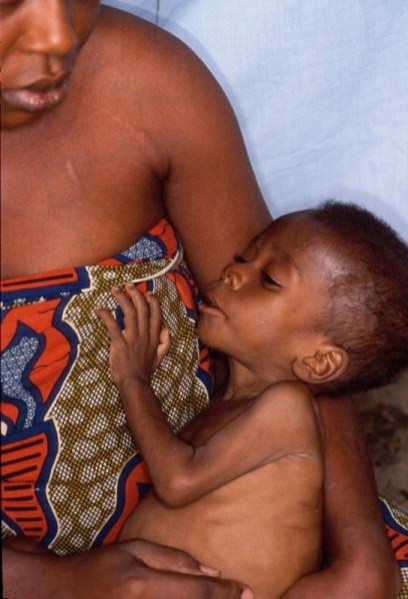

Nigeria has the world’s highest rate of mother-to-child HIV transmission.

Nearly one-third (32 percent) of Nigerians afflicted with HIV work in the sex industry, according to Prof. John Idoko, the director-general for the country’s National Agency for the Control of AIDS.

About 200,000 to 300,000 Nigerians die annually from the disease, leading to a reduction in average life expectancy to only 52 years.

Idoko noted, though, the overall rates of HIV/AIDS infection have fallen slightly, from 4.6 percent to 4.1 percent between 2008 and 2010.

Moreover, over the past decade, the prevalence of HIV in Nigeria has declined by 25 percent.

But the battle against the virus is far from over.

Idoko pointed out that only one-third of the estimated 1.5 million infected Nigerians in dire and immediate need of anti-retroviral drugs have access to such medication.

Hundreds of millions of dollars – some of it from the World Bank – will be spent on HIV/AIDS education and treatment programs over the next few years. Indeed, Idoko has made the ambitious declaration that he wants to wipe out the virus from Nigeria within a few decades.

Like many African nations, Nigeria dragged its heels in facing the gathering storm. The first cases of HIV infection were reported in 1985 – but the Federal Ministry of Health waited six years before examining the prevalence of the virus, by which time 1.8 percent of the population was already infected. That figure jumped to 5.8 percent in 2001, followed by a steady decline.

Still, access to life-saving anti-retroviral drugs has been sporadic at best – by 2006 only 10 percent of HIV-infected Nigerians were receiving antiretroviral therapy, while just 7 percent of pregnant women were getting such treatment.

Part of the problem of providing quality health care to HIV-infected Nigerians has to do with the country’s immense poverty; another factor is the government’s chronic corruption and mismanagement.

In 2010, Nigeria had only 1.4 HIV testing facilities for every 100,000 adults; only 11.7 percent of people aged 15-49 had received an HIV test and come back to learn the results.

This paucity of testing, combined with the high cost of medicine, men's refusal to wear condoms and the reluctance of homosexuals to admit their orientation, has created a massive health crisis.

The AIDS Healthcare Foundation said in a statement this week: “As of today, less than 20 percent of Nigerians have conducted an HIV/AIDS test.”

Now, under President Goodluck Jonathan, Nigerian health advocates, state officials and NGOs are mobilizing to tackle the disease comprehensively.

Michel Sidibe, the executive director of the U.N. Program on HIV and AIDS, said Nigeria will be one of 10 countries that will be the target of a new U.N.-directed plan to encourage preventative treatments of tuberculosis and HIV.

“TB/HIV is a deadly combination; we can stop people from dying of HIV/TB co-infection through integration and simplification of HIV and TB services,’’ Sidibe said.

Dr. Lucica Ditiu, executive secretary of the Stop TB Partnership, commented: “TB is preventable and curable at low cost, yet we still have one in four AIDS-related deaths caused by TB, and this is outrageous.”

Ditiu explained that people living with HIV are 20 to 30 times more likely to contract active TB than people not infected by HIV.

In 2011, she noted, 25 percent of all AIDS-related deaths in Nigeria were caused by HIV-associated tuberculosis.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.