World's Oldest Artwork Uncovered In Indonesian Cave: Study

An Indonesian cave painting that depicts a prehistoric hunting scene could be the world's oldest figurative artwork dating back nearly 44,000 years, a discovery that points to an advanced artistic culture, according to new research.

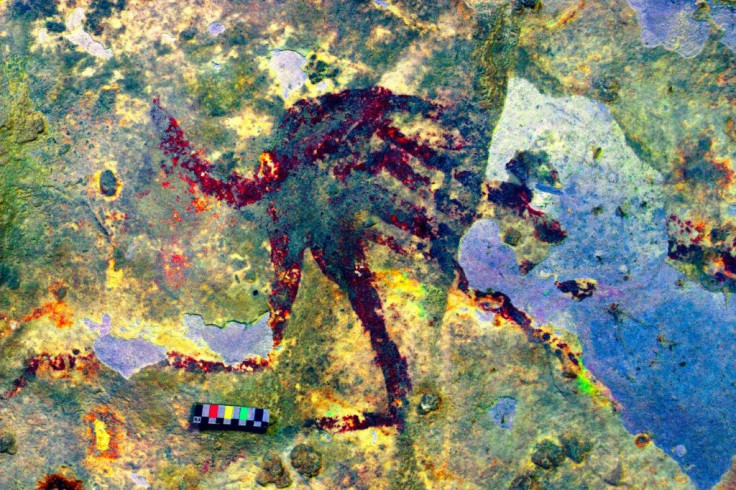

Spotted two years ago on the island of Sulawesi, the 4.5 metre (13 foot) wide painting features wild animals being chased by half-human hunters wielding what appear to be spears and ropes, said the study published in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

Using dating technology, the team at Australia's Griffith University said it had confirmed that the limestone cave painting dated back at least 43,900 years during the Upper Palaeolithic period.

"This hunting scene is -- to our knowledge -- currently the oldest pictorial record of storytelling and the earliest figurative artwork in the world," researchers said.

The discovery comes after a painting of an animal in a cave on the Indonesian island of Borneo was earlier determined to have been at least 40,000 years old, while in 2014, researchers dated figurative art on Sulawesi to 35,000 years ago.

"I've never seen anything like this before," Griffith University archaeologist Adam Brumm told Nature.

"I mean, we've seen hundreds of rock art sites in this region, but we've never seen anything like a hunting scene," he added.

For many years, cave art was thought to have emerged from Europe, but Indonesian paintings have challenged that thinking.

There are at least 242 caves or shelters with ancient imagery on Sulawesi alone, and new sites are being discovered annually, the team said.

In the latest dated scene, the animals appear to be wild pigs and small buffalo, while the hunters are depicted in reddish-brown colours with human bodies and the heads of animals including birds and reptiles.

The human-animal figures, known in mythology as therianthropes, suggested that early humans in the region were able to imagine things that did not exist in the world, the researchers said.

"We don't know what it means, but it seems to be about hunting and it seems to maybe have mythological or supernatural connotations," Brumm was quoted as saying.

A half-lion, half-human ivory figure found in Germany that was estimated to be some 40,000 years old was thought to be the oldest example of therianthropy, the article said.

The Sulawesi painting, which is in poor condition, suggests that a highly advanced artistic culture existed some 44,000 years ago, punctuated by folklore, religious myths and spiritual belief, the team said.

"(The scene) may be regarded not only as the earliest dated figurative art in the world but also as the oldest evidence for the communication of a narrative in Palaeolithic art," researchers said.

"This is noteworthy, given that the ability to invent fictional stories may have been the last and most crucial stage in the evolutionary history of human language and the development of modern-like patterns of cognition."

However, some scientists expressed scepticism about whether the latest find was actually one scene or a series of paintings done over possibly thousands of years.

Depictions of humans alongside animals did not become common in other parts of the world until about 10,000 years ago, one said.

"Whether it's a scene is questionable," Paul Pettitt, an archaeologist and rock-art specialist at Durham University in Britain, was quoted as saying.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.