WWI 100th Anniversary: UK Taxpayers Still Paying £2bn War Loans to Secret Bankers

It's a century since the outbreak of the First World War but British taxpayers are still paying for their country's part in it -- and a handful of banks is cashing in on hundreds of millions of pounds.

Every year £136 million is shelled out in coupon payments to holders of the government debt – War Loans – used to fund the role of troops from the British Empire in WWI.

And the owners of 99% of the £1.94bn (€2.4bn, $3.26bn) WWI debt still around are a secret group of financial institutions.

The UK government's Debt Management Office (DMO) told IBTimes UK that there are over 120,000 War Loan holdings in existence yielding their 3.5% bi-annual coupon payments.

Over 100,000 are worth less than £1,000 in nominal value and held by ordinary members of the public.

"But this large number of holders accounted for only around 1% of the total nominal in issue. So, most of the nominal amount in issue is held by a relatively few financial institutions," said a DMO spokesman.

The DMO declined to reveal the names of the institutions with the five largest holdings of the 3.5% War Loan following a Freedom of Information request, citing various exemptions under the law.

But it did say that the top five holders are nominee companies that own 47.6%, or £923m, of the amount outstanding.

War Loans

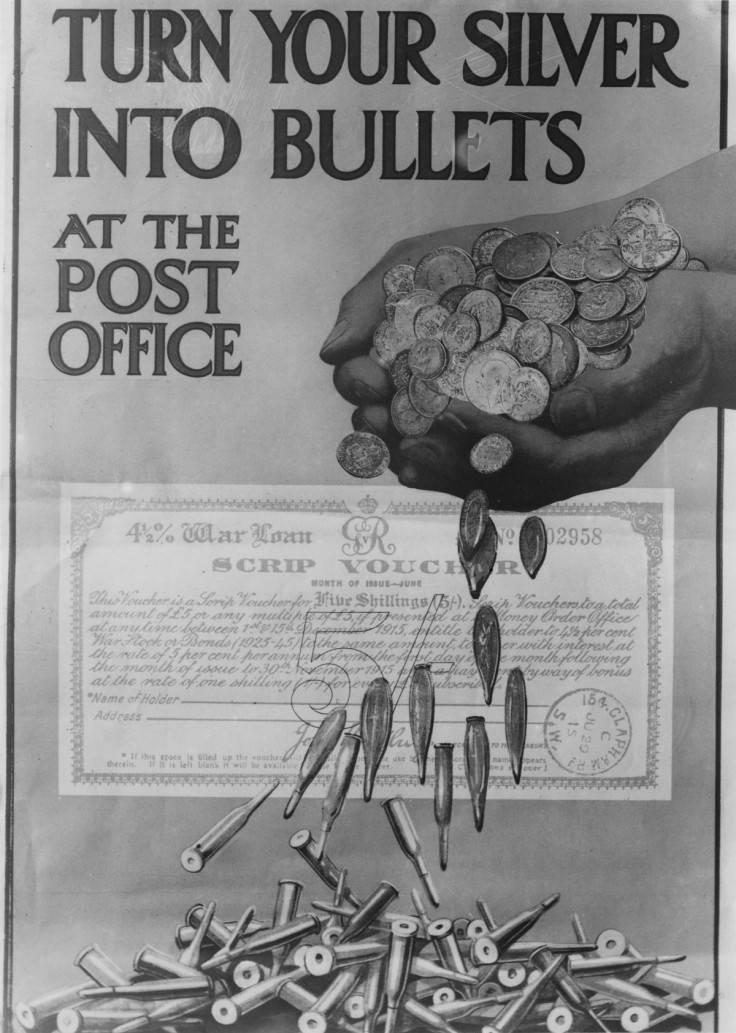

Between 1914 and 1918, the British public were asked to fund the country's war efforts with their savings.

They bought up bonds by the millions, called War Loans, as the government went cap in hand to the people to fund the hugely expensive cost of battle. Arms, ammunition, pay for soldiers – the rhetoric of war is cheap, but the reality of it is not.

The first two lots of War Loanswere issued in 1914 and 1916 and matured in the following decade.

Then came the third push in 1917. These bonds paid out twice a year on coupons worth 5% of the loan's total value. Around 3,000,000 Britons invested.

The bonds were supposed to be redeemed by 1947, having given Britons three decades of half-decent returns in exchange for theirfinancial support in the war.

But in 1932, concerned about the cost of servicing its War Loan debt and unable to redeem it all because of the economic depression, the then chancellor Neville Chamberlain changed the terms.

He redeemed the loans of all those holders who wanted to cash in, even giving a financial bonus to those who acted early.

And for those who wanted to carry on, he cut the coupon payment to 3.5% and converted them to a perpetual maturity date, to be redeemed at some point by a government in the future.

That is why the government is still paying out millions of pounds every year to people and institutions still in possession of these century-old bonds, because it has left them untouched.

Inflation

The problem for holders of War Loans is that their nominal value stays the same. So with every year of inflation, the less valuable the bonds become.

Ordinarily, bonds are relatively short term. So as long as the couponpayments beat inflation, and the nominal amount is redeemed after a few years, the investment is sound.

Over a century, however, inflation has destroyed much of the War Loan's original value.

As it stands, War Loans are being traded at around 85p each – well under their nominal £1 value.

Refinancing?

Now seems like the best opportunity for the government to refinancethis war debt. Gilt yields are near to record lows.

This is in part thanks to the Bank of England's massive quantitative easing programme, which saw it buy up £375bn worth of UK sovereign debt from the markets.

And investors have flocked to reliable UK gilts, a safe haven in the markets, to protect their money from the global financial and economic turmoil around them.

Britain's government can sell 20-year gilts at a rate of 3.34%, at the time of writing. On 30-year gilts, it's 3.45%.

So why not raise the £1.94bn needed to redeem War Loans and pay a lower rate on the debt – cutting the coupon cost for taxpayers – until the bonds come to their natural end years down the line?

The UK Treasury told IBTimes UK it has no plans to refinance WarLoans, though it keeps them under review.

"Any such decision to redeem undated gilts would be taken in accordance with the government's debt management objective, which is to minimise over the long term the costs of meeting the government's financing needs, subject to risk," a spokesman for the UK Treasury said.

"Presently, the government's stock of undated gilts offers relatively low-cost long-term financing with no refinancing risk to the taxpayer.

"Consequently, HM Treasury would need to make a long-term value-for-money judgment that the yields at which it could refinance the War Loan would be likely to remain below the coupon rates on these undated gilts for a sustained period of time."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.