Young Refugees: In Hungary, Doctor Studies X-Rays To Determine Refugees' Ages -- And Fates

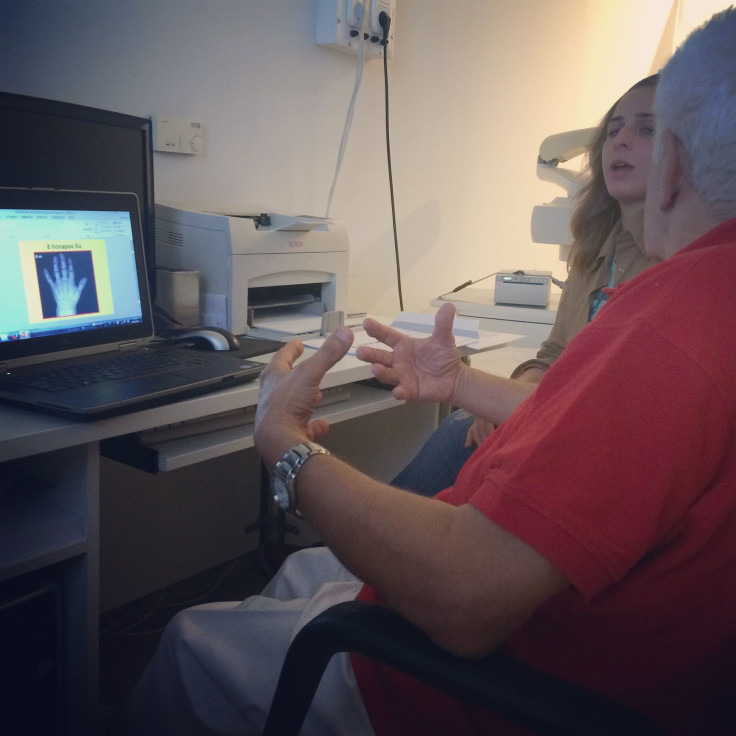

BUDAPEST, Hungary – Dr. Viczena Pal, a 76-year-old radiologist at one of Budapest’s public hospitals, swivels around in his chair inside an empty patient room and clicks open a file on his computer. The file holds X-rays taken of hundreds of the refugee children who have shown up in Hungary without any parents this year. Pal is the doctor -- the only one in the country, he said -- who examines unaccompanied young people’s X-ray scans in order to determine their age -- and therefore their fate.

In what has quickly become one of the worst humanitarian disasters in recent history, European countries are struggling to find the funding and other resources to deal with an influx of refugees from the Middle East and Africa. One of the biggest and most costly tasks is tracking and integrating unaccompanied minors into local welfare systems in Europe. Because of the cost and to avoid overcrowding in state-run children’s homes, the Hungarian government wants to know a child’s age: National policy is that refugees under age 18 receive government protection, including food, shelter and schooling, while adults must fend for themselves.

Many refugees who come to Hungary on their own claim to be younger than 18 in order to receive support from the government, according to Pal and Istvan Kadas, executive director of the largest children's home in the country.

So much rides on Pal’s decision, yet he never actually comes into contact with any of the children. He only reads their X-ray scans. Once he makes his decision about the individual’s age, he sends his report to government officials who make the final call.

Using scans to pinpoint age is not an exact science, Pal concedes. There’s always a margin of error. It is difficult to tell the difference between a 17-year-old and someone who may have recently turned 18, for example.

Pal opened a folder to display the X-ray of an 8-month-old boy. He pointed to the dark spaces between the child’s finger bones. “You see how they aren’t connected? That is how we know he is so young,” Pal said. He flipped to the next X-ray. “Here we have what I concluded after studying the scans is a 17-year-old boy,” he said. “Look at how his bone in his wrist has fused with the cartilage around it. But he could be 18 or maybe even a little older. We can’t tell for sure.”

There are several methods doctors can use to determine age, Pal said, but Hungary can afford to use only one of them. Some countries use a mix of psychological tests, bone density tests, X-rays, as well as other physical exams that require high-end scanning equipment. Hungarian officials must rely on X-rays.

“Every method is susceptible to mistakes, especially with younger children. The younger the child, the more doctors make mistakes,” Pal said. “Using X-rays is a pretty good, cheap and reliable method. But we don’t have a lot to compare the X-rays to because our database for this kind of thing isn’t big enough.”

When unaccompanied minors enter Hungary, the authorities register them in the official system by taking their fingerprints. Then, they transfer them to a state-run children’s home where they stay until officials get them started with the process of verifying their age, country of origin and reason for leaving their home. The medical portion of the process includes getting X-rays, though not every unaccompanied minor is scanned. The only refugee children that get tested by doctors are those that physically look “too close to call,” Pal said, or those who could be older than 18.

Without 100 percent certainty about the age of a given refugee, Pal said, Hungarian authorities must still decide when to let children go and when to keep them under state protection. Inevitably, someone under age 18 could be inaccurately labeled as an adult.

“It happens rarely,” he said. “But it does happen.”

From June through July, the police in Hungary registered 1,397 unaccompanied minors, according to the U.N. refugee agency in Budapest. A children’s home in Fot, the one Kadas oversees, received hundreds of those children, most of them from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq and Syria.

With an official capacity of only 34, the home hosted as many as 300 children at a time, according to a U.N. report obtained by International Business Times. Since then, hundreds of children have fled to other parts of northern Europe to reach a country, such as Germany, better equipped to care for them.

Pal said he read scans for only a few of the Fot home’s refugees because many fled the country before he had the chance.

“I had more last year and the year before that because those scans were of children who actually wanted to stay in the country,” Pal said. “Now, the children coming into the country want to leave right away.”

Still, though, refugees continue to pour into Hungary from Serbia. Authorities here say they expect another 40,000 to reach Budapest by next week. The most vulnerable refugees are the unaccompanied minors, but they are often the hardest to protect, said Babar Baloch, a spokesman for the U.N. refugee agency in Central Europe.

“The Hungarian authorities are in charge of the unaccompanied minors process,” Baloch said. “We try to stay on top of it but we don’t have accurate numbers and it is really hard to track them. What we know about the refugee children in the country comes from the government.”

The Hungarian government’s response has, in general, been one of apathy. Local humanitarian organizations are leading the aid effort. [The government, instead, is building a high fence along the country's southern border with Serbia.]

“We don’t have the money to be doing more scans than we are already doing,” Pal said. “We have a lot of people in the country with cancer. It’s not like we can go up to them and say, ‘Hey, we let 500 Afghanis into the country and we need to give them scans first.’”

As tens of thousands of refugees continue to flow into Hungary, Pal worries he will have to find a way to speed up his efforts -- without hurting his accuracy.

“People’s bones are so different,” he said while clicking through his database. “You can examine the X-rays of a 15-year-old middle-class boy in the U.S. and his bones will look completely different than a 15-year-old boy from, let’s say, Eritrea.” Pal said he is given only the gender of a child, not the country of origin; bones’ appearance is affected not only by genetics, but also by nutrition and other environmental factors.

Pal stopped suddenly on one image in a PowerPoint presentation he said he often shares at conferences. The picture is of the smallest woman on Earth, he said, as registered officially by Guinness World Records. “See? How can her bones be the same as our bones? This picture shows just how tough this process can be.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.