Currency Wars 2013: Japan’s Weak Yen Strikes Big Blow, US Dollar, South Korean Won, Euro Join In The Fray; Global Economies Could Feel The Pain

Although Japanese leaders won’t admit it, the country has quietly declared war on the rest of the world.

After treading economic water for more than 20 years and watching its gross domestic product contract for six of the last eight quarters, Japan has decided to use its currency as a weapon -- and, it hopes, make other countries pay for its recovery. As a result, since mid-November, the Japanese yen has fallen 15 percent against the dollar and 16 percent against the euro.

It’s a risky strategy; in many cases, a falling currency is a sign that a country is in decline, out of favor with global markets that have little confidence in its chances for economic growth.

But Japan has been in the throes of persistent and endemic deflation for years -- in the latest round, wages and prices have fallen for the last six months -- and the country has few options other than to let its currency depreciate markedly in an effort to juice sales of cheaper exports and, in the process, drive GDP higher. And over time as inflation takes hold, Japanese bond yields should rise, attracting more capital into the country to drive government stimulus programs and business loans.

This exchange rate strategy may help Japan in the long run but other countries view it as a nasty shot across the bow, a salvo that in fact could precipitate an all-out global currency war if it drives down the economies of Japan’s allies and neighbors.

“Currency manipulation is a zero-sum game that can only cause countries to respond in a tit-for-tat manner,” said Frederic Chartier, lecturer in Economics and Finance at Babson College.

Fighting Words

If chatter in global economic circles is any indication, this has already begun.

On Feb. 5, French President Francois Hollande warned that France’s efforts to improve their competitiveness could be “destroyed by the rising value of the euro” and he called on euro zone nations to set a “mid-term exchange rate” target to help control the price of their shared currency. “We need to act at an international level to protect our own interests,” he said.

This position was echoed by European Central Bank President Mario Draghi, who left the door open for additional monetary policy easing last month, citing the need to assess the economic impact of the euro’s strength.

In Asia, South Korean President Park Geun-hye said her government would take preemptive and effective steps to ensure stability for the won because a sharp fall in the yen has made business tougher for South Korean firms. "I will take preemptive action to help Korean companies avoid making losses," Park said in a meeting with local business leaders on Feb. 20.

And in Thailand, Foreign Minister Kittirat Na Ranong has put pressure on the central bank to cut interest rates to help exporters and discourage capital inflows, which helped push the baht up 16 percent against the yen in the past three months -- the most among Asian currencies.

This saber-rattling comes on top of ongoing weakness in both the Chinese yuan and U.S. dollar; both countries claim that their febrile currencies are a natural by-product of a listing global economy and not a manifestation of malicious intent. But there are many economists who disagree.

Indeed, it’s clear that the U.S. policy has been to punish the dollar since the recession began five years ago, as the Federal Reserve slashed official interest rates effectively to zero and printed money to buy bonds in quantitative easing programs. The attitude of U.S. officials seems to manifest what former treasury secretary John Connally told the rest of the world in 1971: “The dollar is our currency, but it is your problem.”

Wholesale Suffering

If countries proceed with their threats or escalate currency depreciation activities already underway, the damage to the global economy -- to both developed and emerging countries -- could be disastrous.

For one, monetary protectionism breeds trade protectionism and risks a global meltdown in trade as occurred in the 1930s, which in part paved the way for World War II.

Currently in the U.S., the general tariff rate on turkeys is 6.4 percent, the rate on clam juice is 8.5 percent and the rate on canned tuna is 35 percent. There are also substantial import barriers on milk, cheese, sugar, ethanol, tobacco and fabric.

The U.S. International Trade Commission projects that if the U.S. were to liberalize all significant import restraints at once, the country’s GDP would increase by $2.2 billion (about 0.01 percent), imports would rise by $11.5 billion (about 0.42 percent) and exports would grow by $9 billion (about 0.04 percent).

For another, violent fluctuations in the value of currencies sparked by a currency war discourages businesses from investing, as it makes it more difficult to forecast and plan for the cost of importing raw materials and the revenue generated from selling finished goods abroad.

In South Korea, for example, the strong won is directly responsible for a 51 percent drop in operating profit for Kia Motors Corporation (KRX:000270) in the last three months of 2012. In addition, Kia, the country’s No. 2 automaker, lowered its 2013 sales growth targets. Overseas sales account for upwards of 80 percent of the Seoul-based automaker’s sales.

"[Our] profit is heavily influenced by the exchange rate condition," said Jungwook Wi, a South Korea-based spokespeson for the Kia Motors Corporation. Each 10-won gain in the Korean currency’s value against the U.S. dollar lowers Kia’s profit by about 80 billion won. The won has gained more than 5 percent against the yen this year, after a 23 percent jump last year.

"Exchange rates are out of control," Chief Operating Officer Thomas Oh said. "If the won continues to rise, we will make an utmost effort to cut costs."

In response to the "exchange rate crisis," Kia plans to gradually move away from using the U.S. dollar and expand the approval rate of other currencies including the euro.

South Korea’s export growth has virtually stalled this year, while Japanese exports climbed in January for the first time in eight months -- a reversal in fortunes for the two rivals.

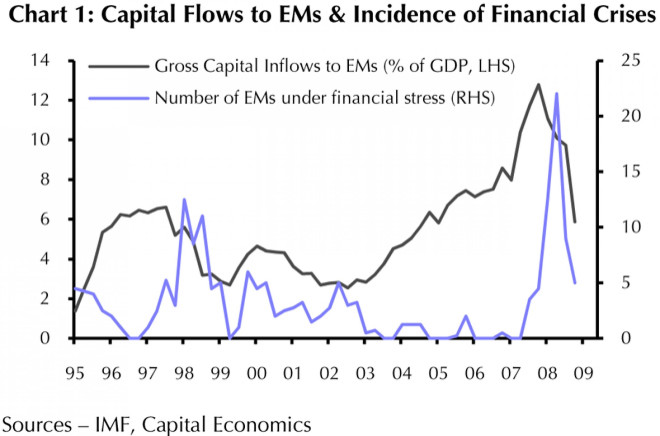

Moreover, behind the battle lines of global currency wars lies a more fundamental concern that declining exchange rates in the developed economies lead to rapid and destabilizing capital inflows to the emerging world.

This tidal wave of Western money -- Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff called it a “tsunami of cheap money” -- not only pumps up asset markets, such as stock and bond exchanges, in emerging countries but it also makes controlling inflation that much more difficult and puts unacceptable upward pressure on emerging market currencies, weakening exports and growth.

For developing countries like Brazil “the result is a dangerous build-up of leverage and finance consumption that ultimately proves to be unsustainable,” said Neil Shearing, chief emerging markets economist at Capital Economics in London.

While Brazil’s exports of goods and services grew by 262 percent over the past decade, the average export growth for other emerging economic powers during that period, such as Russia, India, China and South Africa, was 439 percent, according to a recent report published by the World Bank.

Last year, the Brazilian economy is estimated to have expanded by only 1 percent, compared with 2.7 percent a year earlier and 7.5 percent in 2010. Meanwhile, inflation in Latin America’s largest economy rose at the fastest monthly pace in almost eight years in January, raising concerns that Brazil was sliding toward stagflation. The consumer price index now stands at an annualized growth rate of 6.15 percent -- close to the top of the central bank’s target range. And high-inflation countries can’t dilute their currencies on a sustained basis without damaging their own economies.

Noting the increasingly dire situation in Brazil and the impact of foreign exchange rates on Brazil’s prospects, Laurent Jacque, a professor of international finance and banking at Tufts University’s Fletcher School, said: “Currency wars don’t make sense; it’s a race to the bottom.”

The last full-fledged currency war was in the early 1930s. From 1930 to 1938, 20 countries devalued their currencies by more than 10 percent at least once. Some countries -- including France, Greece and Spain -- employed this tactic more than five times between 1923 and 1938. The successive devaluations were a response to and a cause of the vicious cycle of depression and high trade tariffs that marked that period.

For example, in the U.S., the Tariff Act of 1930 (also known as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff), increased nearly 900 American import duties. By 1932, the average American tariff on dutiable imports was 59.1 percent -- the highest since 1830. U.S. duty for raw sugar, for instance, rose to 2.5 cents per pound in 1930, compared to 1.26 cents per pound in 1913.

“It’s a beggar-thy-neighbor solution, it’s not a solution,” said Bernard Lietaer, an international currency expert who co-designed and implemented the convergence mechanism to the euro and served as president of the Electronic Payment System at the National Bank of Belgium.

Can Japan Print Its Way To Growth?

Japan’s freshly installed prime minister, Shinzo Abe, seems to see it that way. He’s determined to stimulate a moribund economy by ordering the country’s central bank to be more expansionary. Since Abe won the election in December, the Bank of Japan has agreed to a 2 percent inflation target and to make open-ended asset purchases from 2014.

By weakening the yen, Japan shouldn’t expect instant results, economists say, but it could be a step in the right direction that generates the political capital Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party will need in order to begin implementing other reforms, such as opening Japan's economy by joining talks on a U.S.-led free-trade pact.

In a sign of determination to push forward vital economic reforms, Abe promised that Japan would enter trade negotiations to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) after his first meeting with President Barack Obama in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 22. The 11 countries involved in the TPP talks, which together account for 20 percent of global exports, have pledged to remove as many tariffs as possible.

If Japan joins, it will face pressure not only to open up its agriculture market but service sectors such as insurance. Abe's party has long said it would not enter TPP talks without safeguards. Facing opposition from supporters of his conservative party, including those in the powerful farming lobby, Abe offered no promise to eliminate tariffs of up to 777.7 percent on rice -- at least not yet.

“Monetary policy is really the first plank in a platform that would turn the Japanese economy around,” said Karl Schamotta, a senior market strategist at Western Union Business Solutions.

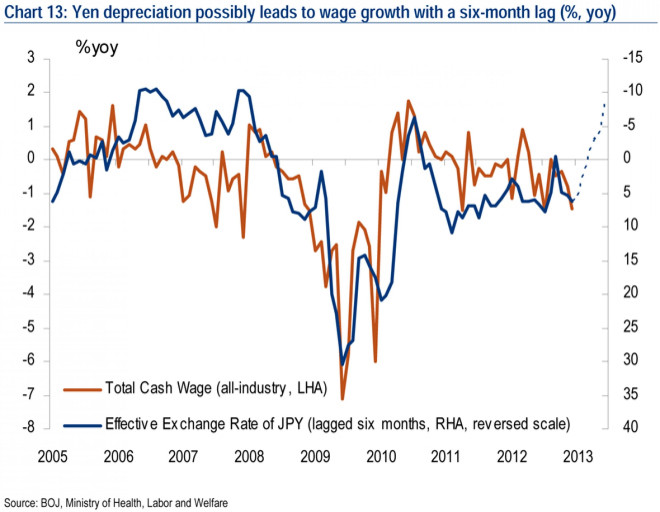

With a sustained 10 percent drop in the yen against the dollar, Japan’s GDP could be boosted by 0.6 percent in the thirased investment and even raid year, according to HSBC economist Izumi Devalier. A corporate earnings revival may then spawn increased wages, creating a virtuous feedback loop.

The impact of yen depreciation on wages varies depending on the period. Given that the yen has depreciated by more than 10 percent year-over-year since November 2012 (the dotted line in the graph), wages may start to get a boost in the second half of this year, according to Masayuki Kichikawa, chief economist at Merrill Lynch Japan Securities.

But rapid yen weakening also brings unwelcome side effects that could eliminate the gains that Japan hopes for from the currency war. Because Japan is growing more and more dependent on foreign sources for fuel -- energy imports accounted for 47 percent of total imports in 2012 (up from 34 percent in 2010) -- its trade deficit ballooned to a record ¥6.9 trillion in 2012, the worst since comparable records began and the second consecutive year that the trade balance dipped into negative territory.

“Normally a decline in the value of the yen would benefit Japan, but with its increased energy imports and resultant trade deficit, that may no longer be the case,” said Jay P. Chandran, professor and chair of the International Business Department at Northwood University.

While Japan awaits the outcome of its aggressive exchange rate policies, other countries that have already joined in the war have seen sufficiently good results that an early end to the contretemps seems out of the question. The U.S, for one, appears to have avoided a worse economic fate because of its loose money strategies.

“If the Fed didn’t engage in quantitative easing, I think the U.S. would be like Europe today,” said Tuft’s Jacque.

And that’s the problem, because the outcome of continued currency escalation is an ugly picture.

“The worst case is that this [race to the bottom] just continues to grow and the current financial system collapses,” said Chuck Butler, the president of EverBank World Markets. “The other option is that finally everyone agrees to back off, the IMF maybe steps in and provides some assistance to some of these countries so they don’t have to keep debasing their currencies, and we start to see this level out.”

Half empty or half full? Trouble is, when global economies are teetering and governments are facing impatient electorates, international cooperation tends to be in short supply.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.