Iraq's 'Stadium Of Horrors' In Ruins, But The Game Goes On

Mohamed Fathi, coach of Mosul's football club in northern Iraq, hardly recognises the ruined soccer stadium once used by Islamic State group fighters to fire rockets and lob mortars from.

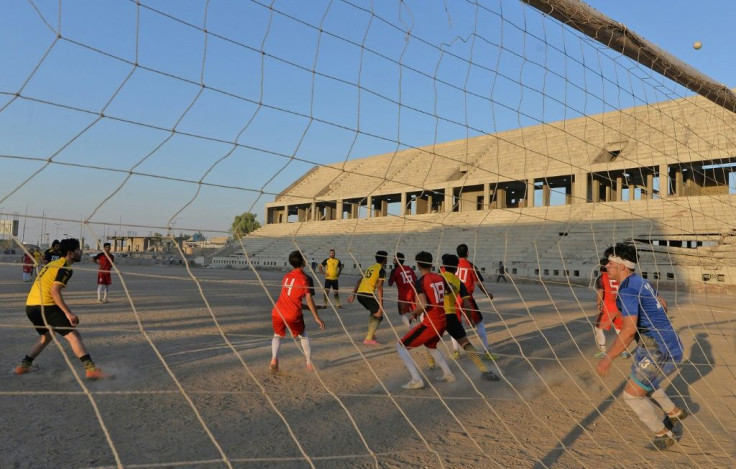

Piles of rubble lie alongside a pitch of bumpy sand. The high concrete stadium tiers surrounding it -- with all seats torn out -- look dangerously close to collapse.

"After this was destroyed, there's no other stadiums in the city to play football," Fathi said, waving his hand at the crumbling building.

"The impact of the destruction is enough to tell you everything that happened here."

Jihadi fighters from the Islamic State (IS) group seized Mosul in 2014, later expanding its so-called "caliphate" to over a third of Iraq and into neighbouring Syria.

In 2017, Iraqi and coalition forces forced the hardened insurgents out in a grinding urban battle that left ancient Mosul in ruins.

The bullet-riddled 20,000-seater stadium, home to Mosul Sports Cub, was not spared, caught up in the deadly battles for control.

Two other smaller stadiums in town were also damaged.

"Sadly the central government doesn't realise that football is what brings life back to a town, its people and its youth," Fathi said. "So things have stayed the same."

Mosul Sports Club was once a solid performing club that produced some of the country's best players.

They include Hawar Mulla Mohammed, who led Iraq to its historic 2007 Asian Cup championship, and who played professionally in Europe.

Decades earlier, Iraq's national squad made its only World Cup appearance in Mexico in 1986.

Mosul's own son, skilled midfielder Haris Mohammed, ably led his country to the rare international honour.

Founded in 1947, Mosul SC played 18 seasons in Iraq's premier league, before its relegation to the first division a decade ago.

With thousands of roaring fans passionately backing their team, locals dubbed it the "stadium of horrors" for visiting teams.

But that ominous label would take on a more sinister meaning with the arrival of IS militants.

"I used to follow soccer matches here, and suddenly out of nowhere convoys of IS militants decked out with guns would show up," recounted Omar al-Mosuli, a resident in his thirties.

"It was a frightening scene, and I used to walk away quietly."

Islamic State's austere and terror-ridden reign was marked by beheadings and shootings.

Like so many other facets of daily life, football changed.

Soccer disappeared as a professional pursuit -- and violence became established a past-time instead.

"Under the stands, IS fighters transformed the space into a massive weapons depot," Mosuli said.

"They set up launchpads inside the stadium to fire rockets during the battle to liberate the city."

He recalled how the extremists forced people to play in long shorts that reached below their knees -- and there was a strict ban on anyone donning jerseys of their favourite international teams or players.

Football matches would be abruptly halted for prayer time, he added.

Amid Mosul's disfigured landscape, its committed players still train on the stadium's dusty pitch a couple of times a week.

There are no other suitable fields to play on.

"We are forced to train here now," Fathi, the coach, explained.

"The club's president and some of the staff even pay for the equipment out of their own pocket," he added.

But the lack of a proper place play for the team is also a reflection of the rampant corruption Iraq struggles with.

The country is consistently ranked as one of the worst performers on Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index.

"A foreign aid agency started reconstructing Mosul SC stadium, but the province's sports authority reassigned the site two years ago to a businessman," Mosul-based sports journalist Talal al-Ameri told AFP.

The businessman sat on the project -- a common occurrence in Iraq.

When a respected former captain of the Iraqi national squad became sports minister, Adnan Darjal, he reviewed the file.

"Due to corruption allegations, the new minister has suspended everything," Ameri added.

But the lack of stadium has not deterred Maytham Younis, the 34-year-old coach of the aptly-named amateur team Al-Mustaqbal, or "The Future".

He urges his young players to train hard, as they practise in a dusty field in Mosul's al-Bakr neighbourhood in front of a small but loyal following of fans.

It is a far cry from the cheering thousands who once watched in Mosul's centrepiece stadium, but it is the best they can do for now as they wait for football to flourish again.

For now, hopes of a return to the glory days the club has seen remain a dream.

"We have plenty of talent," Younis said. "But without a stadium, it's hard for them to get noticed."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.