As Nurx, Providing On-Demand Birth Control And HIV Prevention Meds, Expands, Who Will Benefit?

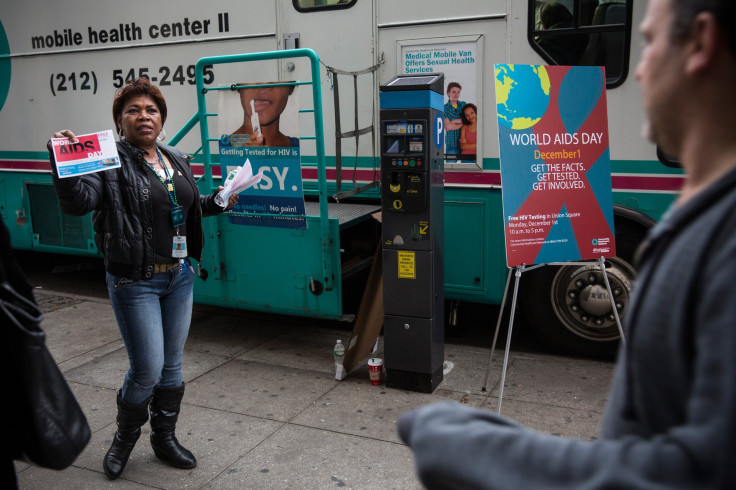

Most people had never heard of Truvada when Courtney Boyce mentioned the HIV prevention drug to focus groups in Washington, D.C., last fall.

“They look at you like you’ve got three heads,” said Boyce, a health communicator for the campaign DC Takes on HIV. “They’re like, 'Why don’t we know about it?'”

Truvada is foreign to many nurses and doctors in the nation’s capital, not just their patients, according to Boyce, even though pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, is recommended by the CDC for people at high risk of contracting HIV. PrEP has been found to reduce the risk of HIV infection by at least 90 percent, yet the pill can’t help those who don’t know about or can’t get it.

San Francisco startup Nurx (pronounced NUR-ex) wants to change that. The app, hailed as revolutionary for prescribing and delivering oral contraception directly to patients in California and New York (so far), last week added Truvada to its California menu. Public health advocates are hopeful Nurx could reinvigorate efforts to lower HIV infection rates in the U.S., which have hit a stubborn plateau in recent years.

As Nurx gains traction, however, key questions remain about who will actually use it, or whether getting medical services with one tap of a finger could have possible long-term side effects for patients, doctors and healthcare overall. In an age of continual innovation, balancing those concerns with the potential of a new idea to drastically improve medicine is a challenge that is increasingly the norm, especially as a growing number of apps provide healthcare services on demand, from offering medical advice to making doctors' appointments.

“In a city like D.C. where PrEP is pretty unknown, it’s hard for people to call up an app and order something if they don’t know they need it or how to take it,” Boyce said. Still, she called the concept of Nurx “brilliant” — when she first learned about Nurx, Boyce said she actually screamed aloud with excitement.

“There is such a need for an app like Nurx to make PrEP more readily accessible,” Boyce said.

In the past eight years, the annual number of new HIV infections in the United States overall has declined, from 49,070 in 2008 to just under 44,000 in 2014. But that progress has been extremely uneven.

From 2011 to 2014, infection rates leveled off, despite efforts like the CDC’s three-year Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning Project, which launched in 2012 and targeted the 12 U.S. cities with the highest AIDS prevalence. And since 2005 certain subgroups — such as black or Latino gay and bisexual men — have still seen increases in their infection rates. In his 2017 budget request to Congress, President Barack Obama requested $788 million for HIV/AIDS prevention and research to “support strategies that are most likely to yield the greatest benefit, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP),” noting that certain populations are “disproportionately affected” by the disease.

For some, those disparities represent an important opportunity for PrEP, like Truvada, to make a difference. “The lack of access causes tremendous detriment individually and at a public health level,” Nurx co-founder Hans Gangeskar said in an interview with International Business Times. The medicine is not a silver bullet — people who take it have to be disciplined about taking it consistently, and they also must be HIV-negative — and it has roused a debate where critics argue it could undermine safe sex through the use of condoms. Nevertheless, PrEP is still regarded as an important tool to help adults reduce their chances of acquiring HIV.

The catch is that “it’s a drug that a lot of people are struggling to get on,” Gangeskar said. “Right now there’s a lot of pent-up demand — people who know about PrEP and need to get on it.” Between Jan. 1, 2012, and March 31, 2014, 3,253 people, a mere fraction when compared with the 44,000 infected in 2014, started taking Truvada, its manufacturer, Gilead, found.

For now, Nurx delivers the sky blue pill, which retails at $1,500 a month, in California, primarily in San Francisco, where most users are located. Patients request Truvada through the app, then answer questions about their medical history. Nurx orders lab tests, and all cases are manually reviewed by a doctor, Gangeskar said. “A lot of users talk to a doctor via secure messaging or on the phone,” he added. “We don't take the doctor out of the equation at all.”

If patients don’t have health insurance, Nurx helps them enroll in an assistance program by Gilead. Those with insurance can get Truvada delivered to them as rapidly as the same day they request it, if they are prompt about getting testing and sending in results.

Nurx has set its sights next on New York City, Gangeskar said. It hopes to expand further from there, including to Washington, D.C. Ultimately, Gangeskar said, “We’re looking to go nationwide as soon as possible.”

But the reality of who will use Nurx in order to get Truvada remains unclear, along with answers to other key questions. Will patients hail from a select crew of well-to-do iPhone owners who stay updated on all the newest apps, who are already diligent about filling prescriptions and are just looking for something a tad more convenient? Could access via the app lessen patients' motivation to see doctors who dispense medical advice or do important testing that's not related to HIV? Those concerns are not limited to Nurx, but the app raises them nonetheless.

“Apps are basically publicized via social media, and smartphones still don’t have full penetration into lower-income populations,” pointed out Dr. Peter Muennig, an associate professor of health policy and management at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University in New York.

In the U.S., 64 percent of the population owned a smartphone in 2014, according to the Pew Research Center. A year later, that proportion had risen to 72 percent. Still, those numbers contain significant disparities.

In 2014, for instance, only half of those making less than $30,000 a year owned a smartphone. But among those who earned $75,000 or more, the proportion soared to 84 percent. Smartphone ownership also varied by level of education. Just over half those with a high school diploma or less owned smartphones, while 78 percent of college grads did.

At the same time, the HIV rate of 2.1 percent among the urban poor in the U.S. is 20 times that of the general population, one CDC-backed study has found. Within that population, the lower the education levels and annual income, the higher the rate of HIV.

Still, the more people start to buy smartphones, the bigger the pool of people who might eventually use apps like Nurx. “Down the line, I do think they have some potential for reaching other populations,” Muennig said.

One reason offering Truvada is both appealing and strategic is because it could rescue patients from having uncomfortable conversations with their doctors and vice versa. But among health experts, the jury is still out on how not physically seeing a doctor could affect the quality of medical care and healthcare costs. Some fear that if patients can get Truvada through an app, they will miss out on conversations about their health that they might otherwise have had with their doctors. Others argue that in some cases, not seeing a doctor might actually help streamline healthcare.

“Doctors aren’t great about talking about sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll,” said Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, New York City’s deputy health commissioner in charge of HIV/AIDS prevention and control, who is working on initiatives to make PrEP more widely available. They have to frankly ask patients, “Are you having sex? Are you using a condom every time?”

Even when, or if, doctors get over their own discomfort in broaching this subject, “There’s a socially acceptable answer to the question, ‘Do you always use condoms?’” Daskalakis added. “The reflex is to say, ‘Yes.’”

By linking doctors and patients virtually, instead of thrusting them into face-to-face conversations, Nurx says it eliminates those awkward, uncomfortable moments — and the potential that patients feel pressure to lie.

In general, if medical and healthcare apps are properly designed, they can actually make medicine more efficient by allowing doctors to focus on genuinely complex medical issues, said Paul Howard, a senior fellow and the director of health policy at the Manhattan Group, a think tank in New York. Not every ailment or medication warrants a visit to the doctor, he pointed out, adding: “An app could fulfill a lot of basic needs.”

That increasingly widespread belief has fueled rapid, recent growth in the healthcare tech industry. Digital health accounts for 7 percent of total venture capital funding, having soared from $1.1 billion in 2011 to $4.5 billion in 2015, according to Rock Health, a venture fund that focuses on digital health. There's Zocdoc, for example, which allows patients to check out doctor reviews and ratings, and make appointments, and Glow, which helps women track their periods and other aspects of their sexual and reproductive health.

Within digital health, on-demand healthcare constitutes a burgeoning slice of the venture capital pie; in 2011, it attracted $21 million in venture funding, or 1.9 percent of all digital health funding. By 2014, its share grew to 6.7 percent, or $289 million, according to Rock Health.

These nifty apps and services are part of a broader shift toward making healthcare more accessible to consumers by giving them what they want, when they want it.

The U.S. has more than 2,000 retail clinics where patients can walk in and be treated for minor ailments, like ear infections, even during evenings and on weekends. New laws in Oregon and California now allow pharmacists there to prescribe birth control for women, and lawmakers in other states, including Hawaii and Colorado, have proposed similar legislation. Getting contraception and Truvada through an app falls along the same lines.

For some, this transformation, along with its myriad advantages, drawbacks and potential unintended consequences, is simply inevitable. Healthcare is constantly evolving, and sometimes what's considered controversial today might be the norm tomorrow.

“That is, in many ways, the direction that the healthcare system is moving,” Alina Salganicoff, a vice president and the director of women's health policy at the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation in Washington, D.C., said of the rise of on-demand services.

She noted how, when home pregnancy kits became commercially available in the late 1970s, that unprecedented access sparked concern about women finding out, in their own homes and without the support of a doctor, that they were pregnant.

But today, Salganicoff pointed out, “people don’t think twice about it.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.