Pandemic Lays Bare Inequalities In Brazil's Schools

The 13-year-old boy selling mangos at the market in Rio de Janeiro was the same age as Vanessa Cavalieri's daughter, studying in the same grade at school.

But while her daughter was home taking classes online, the boy's schooling was interrupted by the coronavirus pandemic, showing how Covid-19 has exposed and exacerbated the deep inequalities in Brazil's education system.

"He hasn't had classes since March 16. He's helping his father sell fruit at three different markets," Cavalieri, a juvenile court judge, wrote in a Facebook post that went viral.

"Meanwhile, Valentina is studying Portuguese, English, science and math online," she said.

"The abyss of inequality between public and private school students, which is already horrible, is only going to get worse."

The wreckage Covid-19 has left on its way to killing nearly 150,000 people in Brazil -- the second-highest death toll worldwide, after the United States -- has not been spread equally.

It has hit the poor and people of color hardest in this sprawling South American country of 212 million people.

Education is one of the areas Brazil's divisions have been laid most bare.

As Brazilian parents, teachers and policy makers wrestle with the questions facing schools everywhere -- is it safe to go back? is the health risk worse than the academic and social costs of quarantine? -- they face an added layer of complexity.

Brazil's 48 million primary and secondary students are essentially divided into two different education systems: elite private schools for the 19 percent whose families can afford them, and public schools for the rest.

With schools slowly starting to reopen, that is forcing some uncomfortable conversations.

"This situation hasn't been easy for anyone or any country, but Brazil's circumstances make it all the more difficult," said Catarina de Almeida Santos, an education professor at the University of Brasilia.

"Online learning for poor students is a fairy tale. They don't have the equipment, internet connection or family resources," she told AFP.

"But we have schools with no clean water, no toilets, no electricity. More than 40 percent have no basic sanitation infrastructure.... If you reopen them, you're guaranteed to get a major increase in Covid infections."

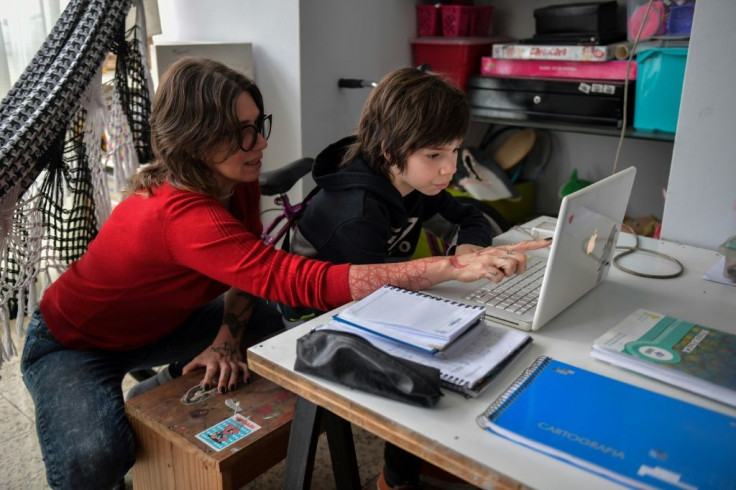

Like many parents, Cinthia Pergola, a social worker and single mom in Sao Paulo, has been scrambling to continue her kids' education, all while working her day job, cooking meals and cleaning the apartment they share with another family.

But, she says, her eight-year-old daughter and nine-year-old son are not learning much in the online version of public school.

"I'm thinking of it as a sabbatical, a year for us to spend time together," she told AFP.

"But as for learning, it's a failure."

Still, she considers her working-class family lucky, she said, as her son studied on their well-loved MacBook.

"We have a computer, a cell phone. Lots of families don't even have internet," she said.

Juliana Stefanoni Iwamizu, an elementary teacher at a Sao Paulo public school, says just 10 percent of her students are attending online classes.

"A lot of them live in the slums, they don't have basic sanitation at home, they depended on school lunches to eat. So the internet clearly isn't an option," she said.

Not to say things are perfect in the private education system, where chaos and confusion have been the norm.

The private system has more resources, but up to half of small- and medium-sized private schools are facing bankruptcy because of pandemic closures, a study found.

They have had to invent distance learning programs as they go, often with conflicting messages from state and local authorities and far-right President Jair Bolsonaro's administration.

"Each school is using a different platform, different rules, different strategies for dealing with the students," said Timmon Vargas, a 32-year-old chemistry teacher at three private schools in Rio de Janeiro.

"None of the planning is coming from the federal government... Education seems to be its enemy."

The chaos has only increased as schools and officials try to chart a path to reopening.

In Rio de Janeiro, for example, private schools were originally set to reopen with strict health protocols on September 14.

But then a massive legal battle erupted, with contradictory information, decisions and announcements coming from the state and local governments, school officials, teachers' unions and the courts.

In an 11th-hour decision, Justice Court Judge Peterson Barroso Simao blocked the return, for now.

He ruled that reopening private but not public schools violated the principle of equality before the law.

"That would only contribute to increasing inequality," he said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.