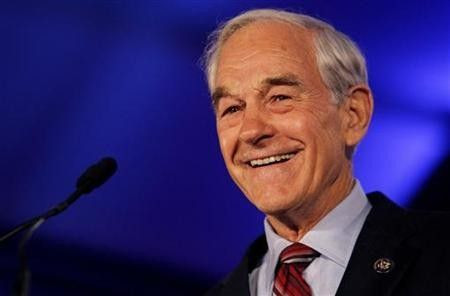

Ron Paul Surges in Iowa: How Far Can He Go?

ANALYSIS

Ron Paul has surged in Iowa, challenging the Republican front-runners and making it clear that he will be a contender in January's caucuses.

A recent Bloomberg News poll showed a four-way statistical tie for first place among Iowa Republicans -- 20 percent for Herman Cain, 19 percent for Paul, 18 percent for Mitt Romney and 17 percent for Newt Gingrich -- and an Iowa State-Gazette-KCRG poll showed Cain leading with 25 percent and Paul in second place with 20 percent.

Paul's Nov. 8-15 average on RealClearPolitics.com, which aggregates data from various polls, is lower: 12.5 percent, putting him in fourth place behind Gingrich, Cain and Romney. But it is clear that his support is increasing. Just how much it is increasing, and whether the increase is sustainable, will become clearer in the coming weeks.

Sure, why not? Larry Sabato, director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia, told the International Business Times when asked whether Paul, a U.S. representative from Texas, could sustain his surge in the polls. The Iowa vote could be quite fractured, with the winner getting in the 30s and several other candidates finishing at 15 to 29 percent.

Why Paul, and Why Now?

Paul does not have the broadest appeal among the Republican candidates, but his support is probably the deepest. That is to say, while supporters of Cain, Gingrich and to some extent Romney have bounced from candidate to candidate, Paul's supporters have remained fiercely loyal to his campaign -- and in a race as volatile as this one, that consistency may help him.

Turnout will probably be lower than in 2008 because there are not the kind of hyper-developed ground efforts like we saw in 2008, 2000 or 1996, Gentry Collins, a former executive director of the Republican Party of Iowa, told The Washington Post. I think that benefits a candidate like Paul because the depth of his appeal will guarantee him a minimum number.

There are several factors contributing to Paul's strength in Iowa. The biggest is the extent of his ground efforts: the recent Bloomberg poll found that 67 percent of likely Republican voters had been contacted by Paul's campaign. By comparison, just 47 percent had been contacted by Rick Perry's campaign, 46 percent by Romney's campaign and 41 percent by Cain's campaign.

Direct voter outreach is much more important in caucus states like Iowa than in states that hold primaries, because caucuses require more voter involvement. Instead of just pulling a lever, voters attend caucuses around the state and give speeches in support of their preferred candidates.

This structure benefits candidates like Paul, whose supporters are dedicated enough to commit that amount of time and effort, and it tends to suppress turnout among people who prefer other candidates but aren't enthusiastic enough about them to attend a caucus.

Paul's backers are made to order for a low-turnout caucus, Sabato told IBTimes. They are highly motivated to organize and show up at the caucuses, which require a couple of hours or more of participation.

Independents can also participate in the Republican caucuses in Iowa, as opposed to many other states, in which only registered Republicans can vote in a primary or caucus. This, too, is to Paul's advantage, because he has more independent support than his competitors.

Paul will benefit more than other candidates from our registration rules, as independents, libertarians [and] Democrats can effectively become Republicans for a night and caucus for Paul, an anonymous Republican operative told The Washington Post. Anecdotally, I have encountered more than a few self-described liberals who will caucus for Paul due to his anti-war stance.

He will also benefit from the support of Iowa's many social conservatives, who have been unable to rally around any candidate for more than a few weeks since Michele Bachmann won the Ames Straw Poll in August. (Paul finished a close second in the straw poll.) He has run ads directly targeting those voters, including one memorable anti-abortion ad in which he described seeing doctors perform an abortion and throw the fetus in a trash can, and then, just a few minutes later, work frantically to save a premature baby.

A Support Ceiling?

Matthew Wilson, a political scientist at Southern Methodist University, said he thought Paul was the latest in a string of long-shot challengers to Romney: the co-successor, along with Gingrich, to the mantle formerly held by Michele Bachmann, Rick Perry and Herman Cain.

Part of it is dissatisfaction with others in the field. That is, a larger percentage of those people who would ever vote for Ron Paul are now inclined to do so, Wilson told IBTimes. There is a large segment that is just never going to embrace his hard-core libertarian philosophy, but he certainly seems to be getting closer to maximizing his share among people who would potentially consider that.

It would be foolish to dismiss Paul in light of his latest poll numbers, but it would also be foolish to disregard the obstacles he still faces. Even Chris Cillizza, who wrote a Washington Post column touting Paul's strength in Iowa, acknowledged, Paul's problem in Iowa, as it is almost everywhere, is that his support base is loyal and getting larger but still too small to comprise a winning coalition.

This is true, as evidenced by the fact that Paul's standing has not changed nationally. He has fluctuated between 5 to 10 percent support in polls conducted since mid-October, but there has been no consistent upward trend.

But Iowa holds the first vote of the primary season, and its caucus structure and conservative electorate make it an ideal state for Paul to make headway -- and if he does do well in Iowa, that could give his campaign the boost it needs to gain national popularity.

Paul is an emerging Iowa force in a race that remains as wide open as at any time in recent memory, Cillizza wrote. That means that Paul's rivals ignore him at their own peril.

Paul himself has said that his showing in Iowa will be a bellwether for the rest of his campaign. If we do badly here, it's a very bad sign, he told Patch.com. If we do very, very well, it's going to send a strong signal to the media that they won't be able to ignore us, and it'll help us in New Hampshire. We're confident that we're going to do well, but exactly what position I'm not sure yet.

Can He Go the Distance?

Wilson said that Paul could definitely do well in Iowa, but the resulting bump would not be enough to propel him to the nomination.

In many ways, any success that Ron Paul has, I think ultimately works to Mitt Romney's benefit, because I don't think Paul is taking many votes away from Romney, he said. He's got his own very niche candidacy ... and so every voter that he's gaining is probably coming from a Perry or a Bachmann or a Cain, and not from Romney. Since Romney rightly feels Paul can't possibly be the nominee, he's perfectly happy to see him continue to climb up the polls in Iowa.

Wilson pointed to Iowa's history of voting for long-shot candidates. Its first-in-the-nation caucus is undeniably important, and the winner of the Iowa caucus has won the Republican nomination in five of the past eight elections (including four of the past five). Sometimes the publicity that comes from winning in Iowa can turn a long shot into a front-runner -- but not always.

In 2008, Iowa caucus-goers voted for Mike Huckabee: a former Arkansas governor, a Baptist minister, and one of the most conservative candidates in the race. The eventual nominee, John McCain, tied for third place with 13 percent -- far behind Huckabee's 34 percent. Twenty years earlier, Pat Robertson, the controversial televangelist, finished a strong second in the 1988 Iowa caucuses, but even among his supporters, few believed he could win the nomination -- and he didn't.

We've seen fringe candidates break through in Iowa before, Wilson said. In 1988, Pat Robertson placed ahead of George Bush in Iowa, but no one honestly thought Pat Robertson was going to be the Republican nominee. I think Ron Paul presents the same phenomenon.

Jamie Chandler, a political science professor at Hunter College in New York City, was more optimistic about Paul's chances, though still measured.

It's plausible that Ron Paul could win Iowa, he said. It will be more difficult for Paul to win New Hampshire since Mitt Romney has built a strong campaign organization there and has been averaging a 20-point lead over the other candidates for months, [and] New Hampshire carries more weight in determining the eventual nominee because it gives the winner a huge boost of momentum through the next several primaries. But, he added, an Iowa win would give Paul and his libertarian beliefs tremendous credibility in the Republican Party and increase his chances of winning New Hampshire. Paul may not win the Republican nomination, but his growing base of supporters, especially among young Republicans, will eventually unseat social conservatives as the party's core constituents.

However, Chandler emphasized that the bar is set high. Paul has a good chance of winning either first or second place, but he will need to win to give him a good shot at winning New Hampshire, he said.

But Sabato said it was too soon to tell how high Paul would have to finish in order to get sufficient momentum.

Momentum is like pornography -- you know it when you see it, he said. We'll see how Paul stacks up once the votes are cast, and how many tickets there actually are out of Iowa. You can finish a close second or a distant second. Is a close third as good as a distant second? It all depends.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.